On May 22, for the Unseen STL History Talks series, I presented a talk on the history of coal and clay mining in St. Louis and Central Illinois. What follows is an expanded recap of the St. Louis part of that presentation — a deeper look at the people, industries, and places that shaped the region from beneath the surface. You can also listen to the full talk above and browse through the accompanying slides.

Note: as part of the event, we raised $175 through cover charges and donations, which we contributed to STL tornado recovery efforts. If you'd like to support ongoing recovery work, consider donating to the City of St. Louis Tornado Response Fund.

St. Louis’s Buried Legacy of Clay Mining

If you live in South St. Louis, there’s a chance your home is standing atop a former coal or clay mine, or adjacent to clay mining operations. For nearly a century, this part of the city was hollowed out by an intense and often hazardous industry that helped build not only St. Louis, but cities across the United States.

Today, this underground legacy is largely forgotten. But dig deep enough — in archives, in maps, and sometimes in your own backyard — and you can discover a bit about why St. Louis looks the way it does.

The Wealth Beneath Our Feet

For millions of years, ancient rivers laid down layers of sediment that compressed into dense pockets of coal and clay — the raw materials that would one day power St. Louis’s industries.

Mining across South St. Louis was closely tied to the region’s early landowners: the Russells, the Christys, and the Binghams. In the early 1800s, these families operated plantations across what is now the Tower Grove South, Bevo, and Dutchtown neighborhoods. Though Missouri’s version of a plantation didn’t always resemble those in the Deep South, these estates did rely on enslaved labor to turn a profit before industrial development took hold.

The transition from agriculture to industry began in earnest around 1820, when James Russell discovered coal on his brother William Russell’s property near present-day Morganford and Tholozan. The coal was close to the surface, making it easy to access and extremely valuable at a time when the city was just beginning to industrialize. The discovery of nearby fire clay soon followed, and mining operations quickly took over the land. What had once been farmland was soon dotted with shallow shaft mines and clay pits. A “coal road” even cut through the Russell estate, facilitating the transportation of materials out of what is now South St. Louis.

These deposits turned out to be particularly abundant in what are now South and Southwest St. Louis neighborhoods, including Cheltenham (along present-day Manchester between Kingshighway and Hampton), Tower Grove South, Dogtown, the Hill, Northampton, and Bevo. Starting in the early 19th century, companies began sinking shallow mines — often only 20 to 60 feet below the surface — using both shaft and drift mining (which allowed them to tunnel horizontally into hillsides) to access the clay and coal below.

One of the few landowners who actively resisted this transformation was Henry Shaw, the English-born businessman and philanthropist best known for founding the Missouri Botanical Garden. Shaw owned property just north of the Russell estate, and when he learned about the expanding mining activity nearby, he took steps to protect his own land from the same fate. Rather than risk its industrial development, Shaw deeded the land to the city for the creation of Tower Grove Park, with a stipulation that it “shall be used as a park forever.” The park officially opened on October 20, 1868 — not just as a gift to the public, but as a deliberate move to preserve the land for posterity.

Clay Mining and Manufacturing in St. Louis

It wasn’t long before another use for the land’s natural resources emerged. In the same areas where coal was mined, rich seams of clay, especially a particularly valuable form called fire clay — were also discovered, leading to the rise of a parallel iindustry.

The clay industry sprung up along Kingshighway Blvd. and Manchester Avenue, both roads representing a dense industrial corridor, home to some of the city’s most important manufacturers. Though much of this history has been erased or buried, you can still find remnants if you know where to look: a multitude of old factories and warehouses, a maze of railroad tracks, a bridge across the River Des Peres that once served the Laclede-Christy Fire Clay factory, and even fragments of sewer pipe or firebrick scattered along the river’s embankment — physical traces of a city built, quite literally, from the ground beneath it.

On the Russell Parker-Russell Fire Clay Mine at Tholozan and Morganford — the site of the first coal discovery by James Russell — featured shafts 80 to 117 feet deep and operated during a time when both coal and clay were being extracted side-by-side. But it wasn’t the only one. Just to the north, the Hunt and McDonald Mine near Arsenal and Gustine was active as early as the 1850s.

The Bingham Mine at Osceola and Gravois was less productive and closed before many of the others, only to be rediscovered in 1930 during road work, decades after it had ceased operation.

Meanwhile, the Christy family was building what would become one of St. Louis’s most enduring clay empires. William Tandy Christy founded the Christy Fire Clay Company in the mid-19th century. His descendants, including Calvin Morgan Christy Sr. and Jr., expanded the operation, eventually merging with the Laclede Fire Brick Company to form the Laclede-Christy Clay Products Company in 1907. They mined clay, manufactured fireproof bricks and industrial ceramics, and became major players in the region’s industrial growth. The Christys built factories, kilns, and offices throughout South City.

The Bingham family also operated a plantation just east of the Christy estate, on the opposite side of Morganford Road. While they’re less prominent in surviving records, their land was similarly mined for both coal and clay and later subdivided for residential development.

These estates were part of a broader economic evolution in St. Louis — from agricultural outposts to industrial workhorses. As the city expanded west and south in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, land that once produced food and lumber was increasingly carved up for mines and factories. The value of what lay underground often outweighed the agricultural worth of the surface, and many estate owners capitalized on the mineral wealth beneath their feet.

Bricks, Pipes, and Terracotta

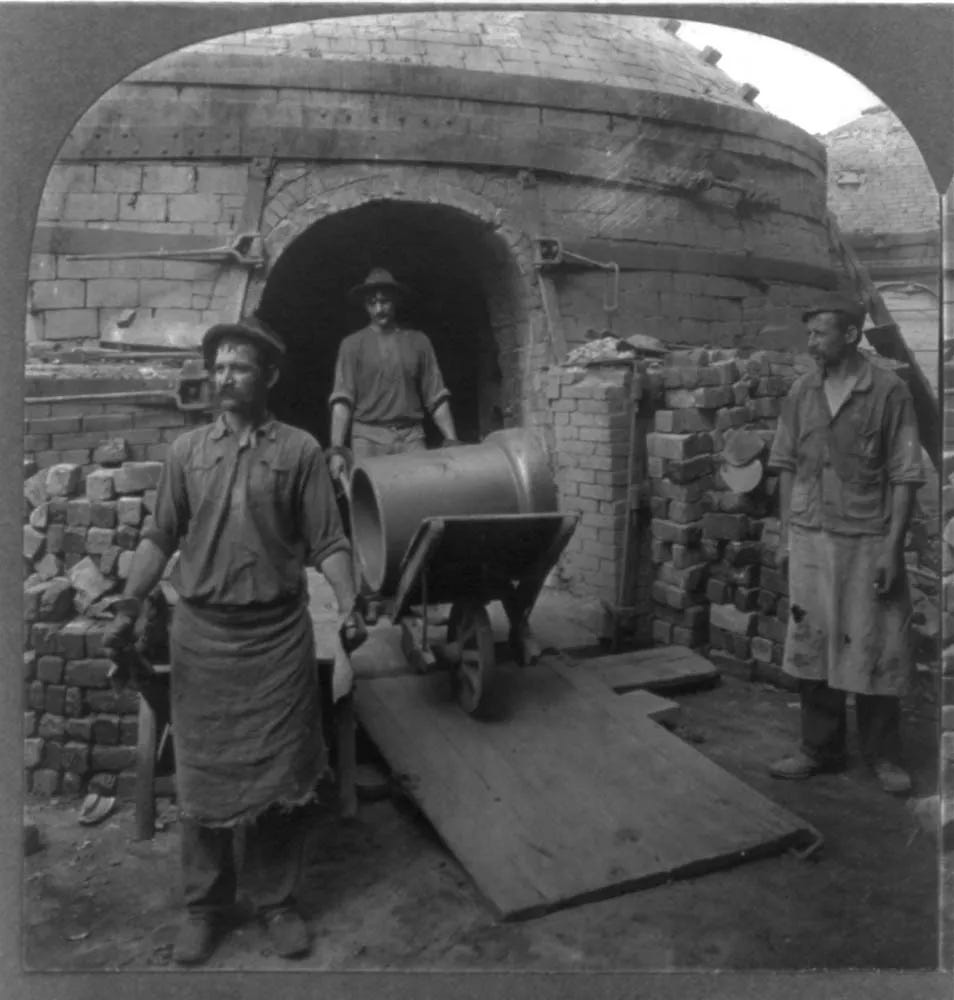

Clay mining wasn’t just about extraction — it was about transformation. What began as lumps of raw material dug from the ground quickly became the literal building blocks of a growing city and a booming industrial economy. Companies like Laclede-Christy and Winkle Terra Cotta specialized in turning clay into useful and beautiful products. Fire bricks, for instance, were essential for lining the kilns and furnaces used in steel and glassmaking, industries that were expanding rapidly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The same clay was also used to create durable sewer pipes and components for industrial equipment — all fired to withstand intense pressure and heat.

But not everything was purely functional. Some of the clay was turned into decorative terracotta tiles, often cast in intricate floral or geometric patterns, adorned many of the city’s finest buildings — from department stores and theaters to churches and schools. These weren’t mass-produced by machines. They were handcrafted, pressed into wooden or plaster molds created by skilled artisans, many of whom had trained in England or Scotland before bringing their expertise to St. Louis.

Cheltenham, in particular, was a hub of this clay-to-product transformation. Located along Manchester Road between Kingshighway and Hampton, the area was home to the sprawling Laclede-Christy plant, the Winkle factory, and a number of affiliated operations. This area included mines, brick kilns, clay storage yards, rail spurs for shipping finished products, and even smelting facilities that supported the area’s larger industrial economy. The concentration of clay-rich soil, proximity to the River Des Peres for water and waste disposal, and access to the expanding rail network made this area ideal for heavy manufacturing.

South City Neighborhoods Born from Industry

As I detailed in my articles about coal mining, the work extracting coal and clay was difficult and dangerous work, and as such, only the poorest workers wanted those jobs. As a result, the workers who labored in these mines in St. Louis were largely either immigrants — many of them Irish or Italian — or Black workers.

Irish immigrants, many of whom had originally settled just north of downtown in what was known as the Kerry Patch, moved westward in search of employment and settled near the Cheltenham clay works, where they worked in the brick and fire clay factories. Their neighborhood eventually became known as Dogtown. Italians also found employment in the mines and kilns and established a strong presence in the vicinity of the clay operations, forming a community that would become known as The Hill.

Black workers also played a critical role, though their presence is less well documented. Photographic evidence from the Missouri Historical Society shows Black laborers working alongside white miners in clay pits. Some sources note a small Black community once existed on or near the Laclede-Christy property during its early years. Many Black laborers likely commuted from nearby neighborhoods such as Mill Creek Valley or Evens-Howard Place (now the Brentwood Promenade), areas that were accessible to the industrial corridor before being largely destroyed by mid-20th-century urban renewal, shopping centers, and highway projects.

A Disappearing Industry

By the 1920s, St. Louis’s once-thriving clay mining industry was beginning to fade. The high-quality fire clay that had fueled decades of brickmaking and industrial growth was running low, and there were richer seams of coal across the river. At the same time, the city’s population was booming, and undeveloped land that had once been used for mining suddenly became far more valuable as real estate. It simply became more profitable to build homes than to dig holes — just as it had once been more profitable to build industry rather than grow fruit trees. Clay mines were closed, factories downsized or retooled, and the industrial footprint slowly gave way to rows of modest bungalows, corner taverns, and small businesses. By the mid-20th century, most of the old mines had been sealed — and nearly forgotten.

But the remnants of this industry are everywhere, if you know how to look. The former Christy plant on Kingshighway is now a shopping center, but its sunken terrain contrasts sharply with the elevated streets and homes to the east. Further north, along Manchester Avenue from Kingshighway to just west of Hampton, the legacy of clay mining is even more visible. This was the heart of the Cheltenham industrial district, where companies like Laclede-Christy, Winkle Terra Cotta, and Hydraulic Brick once dominated the skyline with kilns, smokestacks, and rail lines. Today, the area retains its industrial character — a patchwork of warehouses, manufacturing sites, and storage yards that reflects a history of heavy use.

Though the kilns have gone cold and the shafts have been filled, the story of coal and clay in St. Louis still shapes the land — and the lives built upon it. To understand this part of the city’s past is to see South St. Louis not just as a collection of neighborhoods, but as a place forged, quite literally, from the ground up.

This talk, like so much of what Unseen St. Louis aims to do, was about peeling back the layers of the familiar. It was about showing that our city has stories buried in its foundations — stories of geology, industry, labor, and community. Be sure to listen to my talk and check out the slides, which include many more photos than I had space to include here.

If you’re curious to learn more about Illinois mining, which I addressed in the talk, I have a two-part series on coal mining in Macoupin County, Fuel for the Fire: The Story of Central Illinois Coal Mining and Forged in Rebellion: Organized Labor in Central Illinois Coal Mines.

And if you enjoyed this look back at the mining industry that built St. Louis, I encourage you to subscribe to Unseen St. Louis, or consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support my work and help me tell more stories like this in the future. And please be sure to share!

Share this post