Fuel for the Fire: The Story of Central Illinois Coal Mining

The history of the industry that powered St. Louis

Welcome to Unseen St. Louis, where I dig into the overlooked corners of our city’s past. In honor of May Day, I crossed the Mississippi to uncover the coal mining boom in Illinois — the first installment of a two-part series on the industry that helped power St. Louis.

Long before the electric age, St. Louis was powered by coal — much of it dug from the ground in central and southern Illinois. These mines, many located less than an hour from downtown St. Louis, fueled the city’s insatiable demand for energy to heat homes, run factories, and keep the railroads moving. This coal helped transform St. Louis into a Midwest industrial powerhouse, even as it darkened the skies and coated every surface in soot.

In this first of two articles, we’ll explore how the Illinois coal industry began, how it reshaped entire towns and brought people to the Midwest (including my own), and what life was really like underground. Part 2, Forged in the Furnace: Rebellion, Legacy, and the Decline of Illinois Coal, explores the history of Illinois miners and organized labor, and how Macoupin County miners captured the heart of labor organizer Mother Jones, who asked to be buried among them.

Illinois is built on coal — literally

Coal mining was a defining industry for Illinois. To date, coal has been mined in 76 of the state’s 102 counties, and more than 7,400 individual mines have operated since commercial mining began. You can explore the full extent of the state’s mines on the ILMINES interactive map, which reveals just how much of Illinois sits atop tunnels and shafts — a literal foundation of coal.

French explorers Louis Joliet and Père Marquette first noted the presence of coal in the area, spotting black seams of combustible rock along the Illinois River near Utica in 1673. Over a century later, in 1810, William Boone and his indentured servant, Peter, began hauling coal from outcroppings along the Big Muddy River in Jackson County. They floated it down the Mississippi and sold it in New Orleans, where it was used for blacksmithing. That venture marked the first known coal mining operation in the state.

After the Civil War, railroads opened up vast new markets, and coal became indispensable both to power the trains and the industries along the tracks. By 1882, Illinois had 685 active coal mines across 43 counties that employed over 20,000 workers. By 1876, wood was still America’s dominant energy source, but by the turn of the century, coal had taken the lead, supplying over 70% of the nation’s power. It drove steam engines, factories, steel mills, and railroads.

And to dig up all that coal, mines needed lots of workers. The first miners were native-born settlers, many descended from English, Scottish, and Irish immigrants. Then, between 1890 and 1922, a flood of European immigrants — from Italy, Austria, Croatia, Poland, and elsewhere — poured into the state. Most were unskilled and spoke little English, and mining was one of the few jobs open to them. My great-grandparents, Janko and Anna Bellavich, were among them. They came to the US from Brig, a town in Croatia’s Istrian peninsula, in 1911. By 1919, they had settled in Benld, a new mining town in Macoupin County. Their son, my great-uncle Charlie, eventually followed Janko into the mines.

Black workers moving north after the Civil War also found work in the coal fields of Illinois. As I will explore in more detail in part 2, during labor disputes in the early 20th century, including at what would be known as the Battle of Virden, mining companies brought in Black workers from the south as strikebreakers, deepening existing racial tensions. Sadly, what these men found in Illinois was often little better than what they had left behind. Segregation, discrimination, and even violence — including terrorism from the Ku Klux Klan — greeted many who sought a better life in Illinois.

The mining boom of Macoupin County

Macoupin County, just an hour northeast of St. Louis, emerged as one of Illinois’s most prolific coal-producing regions. Its first recorded mine — the Weer Shaft in Carlinville — opened in 1867. By 1879, there were 15 mines scattered across the county: nine shaft mines, three slope mines, and three strip mines. Towns sprouted almost overnight wherever coal was pulled from the ground. Over time, dozens of mines would open in the county.

One of the most transformative developments came in the early 1900s, when the Chicago and North Western Railway identified coal from the Gillespie area as unusually high-quality — easier to mine, cleaner-burning, and more efficient than coal from other parts of Illinois. To capitalize on this, the railway established the Superior Coal Company and quickly sank three major mines: No. 1 in Eagerville, No. 2 in Sawyerville, and No. 3 in Benld. A fourth, Mine No. 4 in Wilsonville, soon followed. None of these towns existed before the mines — they were built around them.

People arrived in droves, drawn by the promise of steady work. Gillespie, which had been settled in the 1820s, exploded, with its population jumping from 873 residents in 1900 to over 2,000 just six years later. Superior Coal alone employed more than 1,100 miners, and by 1908, its three original mines ranked 1st, 2nd, and 5th in the state, producing a combined 1.6 million tons of coal.

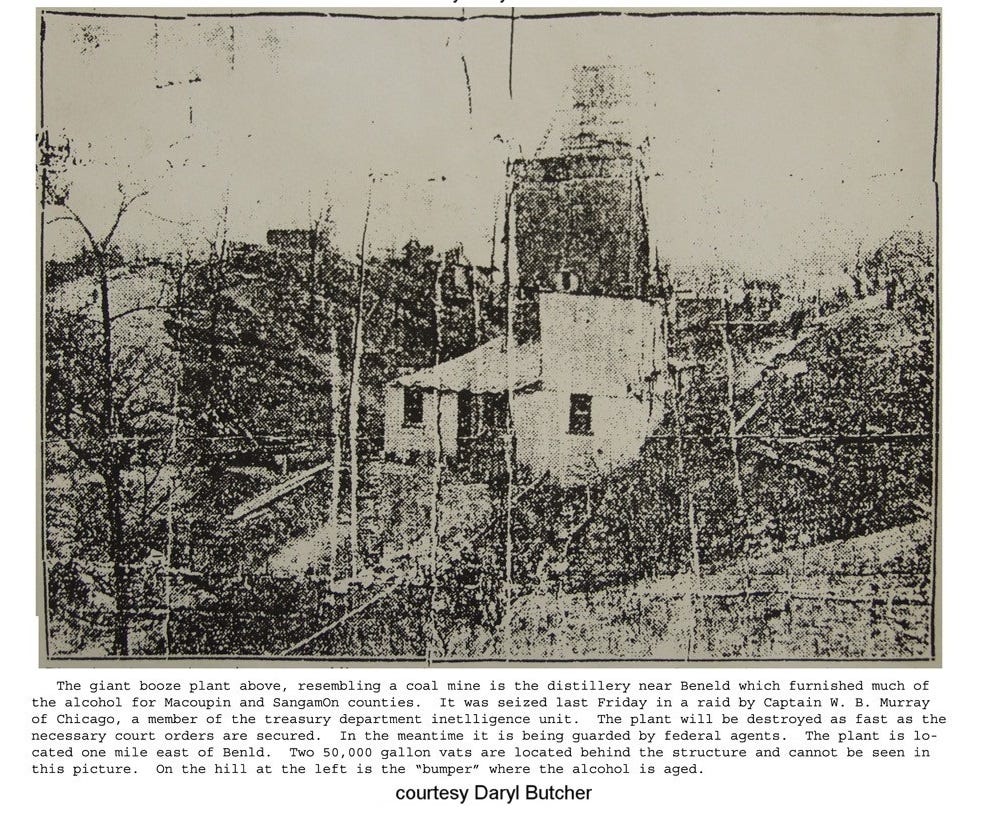

Not everyone felt welcome in Gillespie. In 1904, a group of Italian, Lithuanian, and Austrian immigrants working in the Superior mines set out to build their own town — one free from the prejudice they faced from American-born residents. They named it Benld, an acronym of landowner Ben L. Dorsey. By 1910, the town had grown rapidly, boasting a bank, flour mill, brickyard, 30 taverns, a newspaper, and a school filled with children speaking at least 17 different languages. It also developed a reputation for its colorful underbelly. During Prohibition, Benld’s so-called Mine No. 5 was actually a secret still, capable of producing 100,000 gallons of moonshine. It operated until federal agents raided it in 1928. And, as my father recalled from growing up there, the town was also known for its numerous brothels.

This dense cluster of mining towns — nine within five miles of Gillespie — came to define the county’s identity. But unlike classic company towns such as Glen Carbon, where coal companies owned nearly everything, Macoupin’s communities maintained a degree of independence. Miners typically rented small homes rather than living in tenements, and company ownership of local shops was limited.

While coal brought jobs and prosperity, it also demanded backbreaking labor in dangerous, often deadly conditions. To understand the full weight of Illinois coal mining’s legacy, we have to look at what life was like inside the mines.

The hard reality of a miner’s life

In the early days of coal mining in Illinois, stepping into a mine meant entering a world of danger, isolation, and relentless physical labor. Most miners were essentially independent contractors, assigned a section of the mine and paid by the carload. Early on, there were no salaries, job security, healthcare, or responsibility taken by the company in case of injury or death. State mining laws offered little protection.

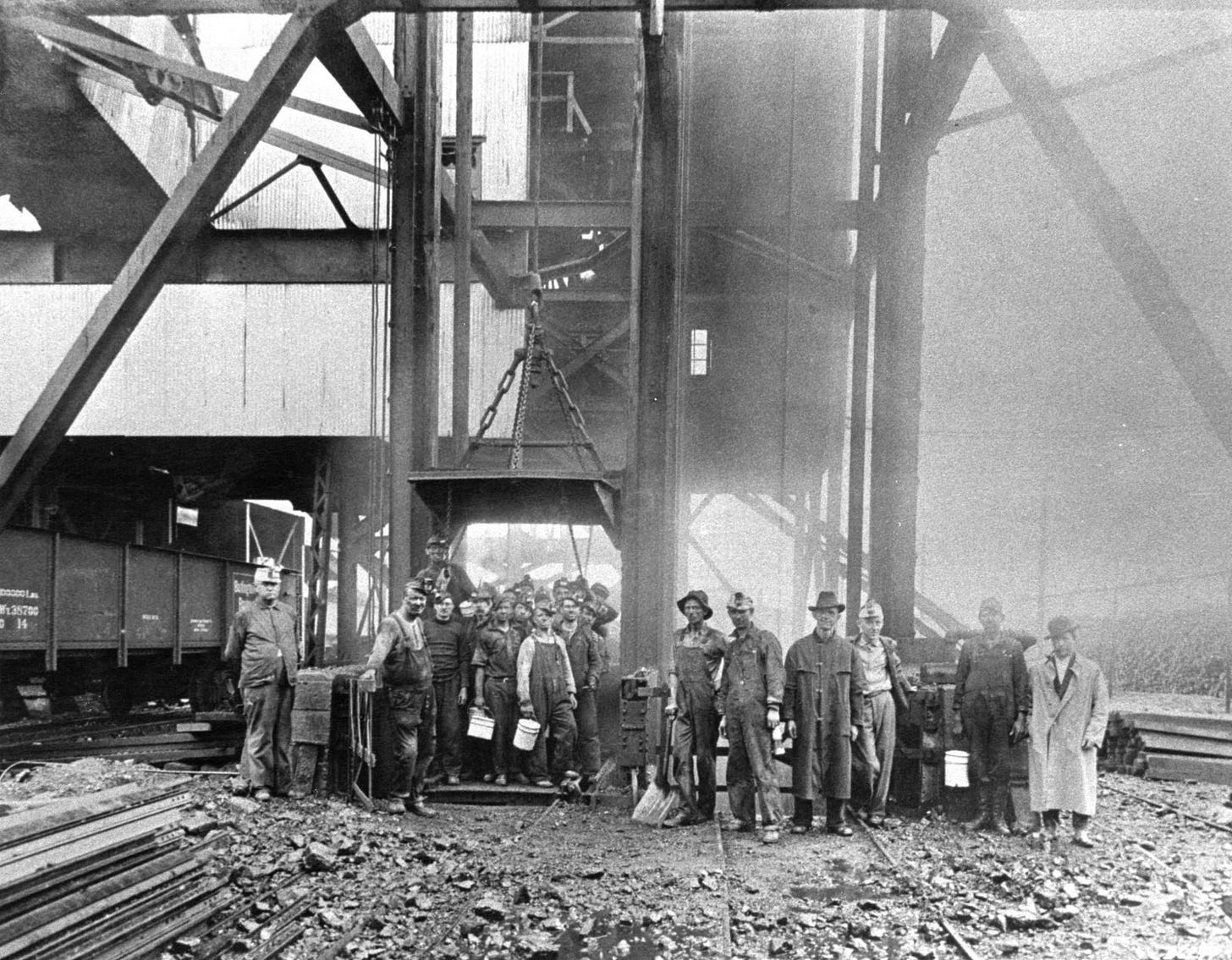

Each day the mine was open, men would gather before sunrise at the mine entrance with their lunch buckets and canvas caps fitted with paraffin or carbide lamps. Once inside the cage — an open-sided elevator — they dropped 200 feet or more into what one observer described as a darkness “comparable to nothing one would call dark on the surface.” From there, they walked or rode mule-drawn coal cars up to two miles through black tunnels to reach the working face.

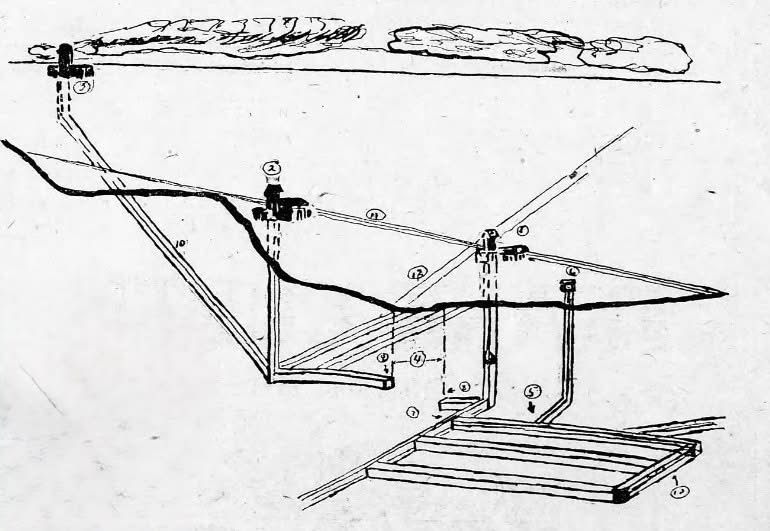

The most common system used was the “room and pillar” method. From the main tunnel, horizontal entries branched off like ribs, with rooms carved out between thick coal pillars left in place to support the roof. Each room was about 12 to 25 feet wide and could stretch several hundred feet into the seam. Two men typically worked each room — one miner and one helper. The miner did the skilled work: cutting, drilling, and blasting. The helper handled the hauling and cleanup.

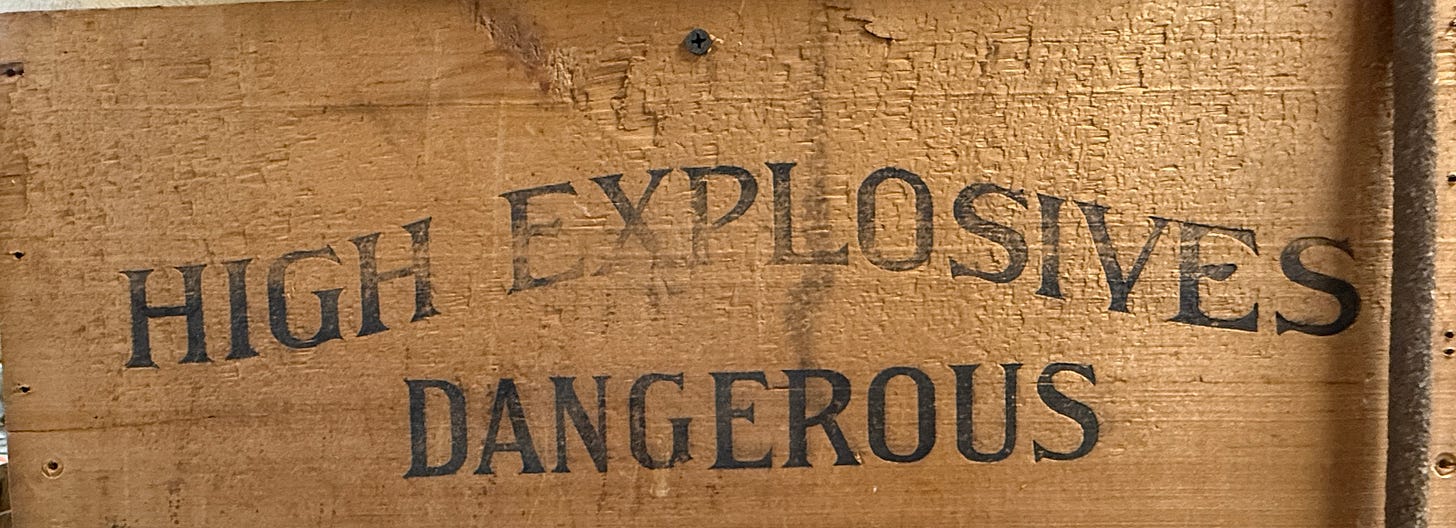

To begin a day’s work, the miner lay on his side under the coal face and hacked away at the base with a pick to undercut it — a task known as shearing. Then came the drilling. Using a hand-cranked drill, he bored holes into the coal face to pack with black powder. The explosives were detonated at day’s end by a designated shot-firer, who had to light multiple charges and reach safety in under two minutes.

The next morning, the men returned to shovel the coal into low metal cars. The work was done crouching in the flicker of their carbide lamps, and the air was thick with dust. In the early days, there were no hard hats or respirators. Just a pick, a shovel, and the strength to move up to a ton of coal a day.

Miners were paid only for the coal that made it into the cars. Waste product — rock, slate, and sulfur — was called slag, and did not count towards a miner’s pay. This slag would be hauled out and piled outside the mines, forever changing the landscape (and leading to various environmental issues later on). Workers tracked their output using metal tags called “checks” tied to each load. One frequent miner grievance was the company undercounting their work. Only with unionization did workers gain the right to have union checkmen monitor the scales.

While miners dug the coal, there were many other jobs in a mine. Timberers reinforced ceilings with wooden posts; cagers and engineers operated the hoisting cages; and boilermen kept the above-ground steam plants running. Mechanics and blacksmiths maintained the gear and shod the mules that pulled the cars.

Above ground, coal mines included ponds providing water for boilers and washhouses for the men and mules. There were also scale houses for weighing and tipples — tall timber-framed buildings that housed the hoisting and sorting machinery. A fan house kept air moving through the shafts. A powder house stored the explosives. A coal washer separated the last impurities before shipping.

As time went on, technology crept into the pits. Gillespie’s mines were among the first in the region to adopt cutting machines that resembled giant chainsaws on wheels. These tools made fast work of the coal face but introduced new hazards. Some mines also switched to electric locomotives, using overhead power lines to pull cars instead of mules. Pneumatic and electric drills were introduced in the 1930s.

Mining depended on child labor

For many Illinois families in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, sending boys into the mines wasn’t a matter of choice — it was a matter of survival. With large families to feed and low wages for adult miners, children often went underground as young as 9 or 10. Parents would get around regulations by claiming their sons were small for their age, so they could keep working underground unnoticed by inspectors or company officials.

Young boys worked as mule drivers or trappers, opening and closing the ventilation doors. On the surface, boys and girls served as slate pickers — some as young as nine — sorted out waste rock before coal was shipped to market. My great-aunt Rose had to pick coal, and many years later, would tell her family how much she hated it.

Born in 1895, Joe Ozanic of Westville IL started working in the mines in 1910 at just 14 years old. “I wasn’t old enough and my bones weren’t even sturdy enough to do that kind of work,” he recalled decades later. But there wasn’t much of a choice. Joe's father, an Austrian immigrant who came to America in 1890, was already working in the mines to support his family — nine sons and three daughters — on meager earnings. As Joe put it: “Like father like son, we wanted to be coal miners. In fact, we had no choice except to be coal miners.”

Mining Was a Dangerous Business

For miners, danger was as constant as the dust in their lungs. The risks began the moment a shift started. Workers descended deep into the earth on cage elevators without side rails or lighting, where a sudden jolt or slip could throw a man into darkness or worse.

Once in their room, miners had to undercut the coal with short-handled picks — their bodies often directly beneath tons of overhanging rock. Chester L. Morton of Pana recalled his father explaining how he would tap the roof with his pick and study the rock’s color to detect instability. “His life and his buddy’s depended on understanding the rock,” Morton remembered, “and using good sense and experience to avoid the danger.” Even then, safety was never guaranteed. One weak seam, one misjudged slick spot in the coal, and the whole roof could come down.

Shot-firers, who blasted the coal loose with first with black powder and later dynamite, worked alone after others had left the mine. They drilled deep into the face, packed powder or sticks into the holes, and lit the fuses — sometimes several at once. If the charges didn’t fire cleanly, the face could erupt in an explosion of coal dust and gas, igniting the very air around them. A misfired blast could also break the coal into worthless fragments or, worse, cause a deadly collapse.

In addition, falls, runaway mine cars, suffocation, and exposure to toxic gases were constant threats. As Jim Alderson of the Gillespie Museum described, miners often rode the chains between cars, keeping the cars spaced apart with their bodies. They could easily fall off or be crushed between them. Even the electric lines used to power equipment were strung overhead and uninsulated, often causing electrocution.

Then there were the toxic or suffocating gases: “firedamp” (methane), “blackdamp” (carbon dioxide/ low oxygen), “whitedamp” (carbon monoxide), and “stinkdamp” (hydrogen sulfide). Early on their only warning system was a canary in a cage — later replaced by open-flame safety lamps whose glow changed when exposed to hazardous gases. Needless to say, ventilation was essential, but imperfect. Fans pushed air through the maze of tunnels, with “crosscuts” and entries carefully opened and sealed to direct the flow, but could not compensate if a miner exposed a pocket of bad air.

Needless to say, accidents were a grim reality in the coal mines, despite the precautions taken. Between 1880 and 1907, at least 24,434 miners died in U.S. coal mines — likely an undercount — with more than 3,100 deaths in 1907 alone. Illinois’s worst mining disaster struck in 1909 at the Cherry Mine, where a hay fire ignited a blaze that spread through wooden supports and air shafts, killing 259 men and boys by suffocation, burns, or failed rescue attempts. The tragedy helped spur early mine safety reforms. Decades later, on May 8, 1942, Macoupin County's Superior Mine No. 1 saw another disaster that began with a methane release and fire. Though the mine was under evacuation orders, several miners got trapped by unexpected floodwater and drowned. Investigators found that workers had unknowingly breached the old, decommissioned Dorsey mine, which still held dangerous pockets of methane and water after being sealed shut for decades.

At the Gillespie museum, Jim Alderson handed me a folder thick with pages detailing just miner deaths in Macoupin Co. Here are just a few:

September 20, 1915: Joseph Marchetti, of Virden, cager, age 48 years, married, was killed by being crushed between two pit cars in the Royal Colliery Company’s mine, Virden, Macoupin Co. Deceased was helping to cage a car of coal. He was pushing the car onto the cage when it struck something and bounded back, catching him between it and the one immediately in the rear. He leaves a widow and five children.

December 5, 1922: Howard Ronk, of Girard, miner’s apprentice, age 19 years, single, died from burns received in an explosion of gas three days previous in the Illinois Coal and Coke Corporation’s No. 4 mine.

August 7, 1916: Charles Phillips, miner, age 40 years, single, was killed by falling slate in Consolidated Coal Company’s No. 7 mine, Staunton, Macoupin Co. He leaves two dependents, mother and sister.

January 4, 1910: John Proberts, driver, age 19 years, single, was severely injured by a kick from a mule that he was driving in mine No. 3 of the Superior Coal Company, Gillespie [Mount Clare]. He was taken to his home when he died from the injuries the following day.

Even with all the dangers in the mines, possibly the worst damage occurred within miners’ bodies. Coal dust filled the lungs despite miners using bandanas or, later, respirators. Over time, miners developed black lung disease — a slow, irreversible suffocation as coal particles scarred and hardened the tissue of the lungs. As Dan Fisher noted, “If the big rocks don’t kill you, the little ones will.”

Mining could be noble and a source of pride. But there was no disguising what it was: a dangerous, grinding life. And for generations of Illinois men and children, it was the only way to make a living.

The slow fade of a coal empire

The story of coal in Illinois gradually shifted from one of booming towns to widespread decline. By the mid-20th century, a mix of economic, technological, and environmental pressures left coal communities across central and southern Illinois struggling to survive.

Mechanization boosted productivity but eliminated thousands of jobs. Cutting machines, conveyor belts, and electric locomotives made coal extraction faster — and workers expendable. Local coal seams were also running out. After 80 years of mining, much of the coal in central Illinois was either gone or too expensive to access. Production shifted to southern Illinois, where newer, deeper mines modernized quickly. Older coal hubs such as Macoupin and Sangamon Counties fell behind. The rise of strip mining only accelerated the trend, replacing underground labor with smaller, more efficient surface crews.

Coal’s dominance was already slipping by the 1920s, as petroleum and natural gas emerged as serious competitors, and the Great Depression deepened the pain. Railroads — once the biggest consumers of coal — began upgrading their engines and eventually switched to diesel. Home heating followed a similar shift. Meanwhile, the high-sulfur “soft” coal mined in Illinois was becoming a growing liability. It contributed heavily to air pollution, especially in nearby St. Louis, which by the 1930s had some of the worst air quality in the country. On “Black Tuesday” in 1939, the smog was so dense that daylight nearly vanished. At the recommendation of future mayor Raymond Tucker, then “Smoke Commissioner,” the city passed a landmark 1940 ordinance banning the use of high-sulfur coal and requiring cleaner-burning anthracite.

New Deal programs brought a temporary boost to the coal economy. Labor reforms secured rights for union organizing and collective bargaining. Social Security introduced safety nets for workers. Mine safety laws and employer liability rules made mines marginally safer and more humane. And during World War II, the coal industry enjoyed a final, patriotic resurgence. Miners were once again deemed essential, pushing output to new heights to meet wartime needs — even as they endured wage and price controls.

But after the war, the slide resumed. Mines continued to close. Each round of negotiations brought higher wages and safer conditions, but there were fewer jobs to be had. Population dwindled in coal towns, and main streets lost their shine. While other regions embraced postwar prosperity, the coal belt was left behind.

Gillespie remained one of the few towns to maintain its population into the second half of the century, buoyed for a time by its size and infrastructure. But in many of the surrounding communities, the coal industry’s retreat left behind boarded-up businesses, vacant homes, and a slow, quiet fade from the prominence they had once known.

A legacy that still burns

The industry’s decline hasn’t left a clean break. In towns like Benld and Gillespie, where generations of miners once toiled underground, the mines haven’t been forgotten — or gone. The ground itself is still shifting. Long-abandoned shafts and hastily reinforced rooms have caused mine subsidence, leaving homes cracked, foundations sinking, and in one dramatic case, forcing the demolition of a brand-new elementary school in Benld built atop an old mine.

Illinois has more than 800,000 acres of undermined land, with over 330,000 homes believed to sit above old coal mines — most of which were never filled in. While entrances were sealed, the vast underground networks remain intact. For many residents, subsidence insurance is now essential — a reminder that the past still lies just beneath their feet.

Below is a small section of a hand-drawn map of the Little Dog Mine in Gillespie, overlaid with city streets for context. The mine itself stretches far beyond the city limits, extending deep into the surrounding farmland.

The environmental impact of mining still lingers. Drive through coal country and you’ll spot low hills rising from the landscape — old slag heaps, now covered in scrubby growth, too damaged for farming, housing, or most other uses. Although the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 requires companies to clean up abandoned sites, enforcement has been inconsistent. Of the estimated 32,500 acres of post-1977 mines needing reclamation in Illinois, only about 6,600 have even been partially restored.

The mines may be closed, but their scars remain.

This first chapter of Illinois’s coal story centers on the grit and resilience of the miners who labored underground. Given the dangers they faced, it was only natural that they would begin to fight — not just for better pay and safer conditions, but for the right to shape their own future. In the next installment, we’ll explore how that struggle ignited a full-blown rebellion in Macoupin County and led to the creation of a breakaway union. Stay tuned for part two: Forged in the Furnace: Rebellion, Legacy, and the Decline of Illinois Coal.

And if you enjoyed it, please support this work by sharing it with your friends or upgrading to a paid subscription.

Much gratitude goes out to Jim Alderson at the Illinois Coal Museum at Gillespie, who gave me a tour of the museum and explained many of the artifacts there. If you enjoyed this topic, I encourage you to visit the museum, which is loaded with memorabilia and artifacts from when mining was king in Macoupin County.

Sources

Abigail Bobrow, "Built on Coal", Storied Magazine, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, October 4, 2021.

Casey Bischel, "Coal mining has deep history in Southern Illinois", The Register-Mail (Galesburg), January 8, 2018.

“Coal Mines and Mining,” Macoupin County ILGenWeb.

Terri Dee, "Abandoned IL coal mines pose health, environmental complications", WSIU Public Broadcasting, June 24, 2024.

"First Coal Mine in Illinois", Southern Illinois Tourism, Jackson County, Illinois.

Dwyer Gunn, "A Look Inside the Coal Communities in the Illinois Basin", Pacific Standard, July 2017.

Mara Lou Hawse and Dianne Throgmorton, Tell Me a Story: Memories of Early Life Around the Coal Fields of Illinois, Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, 1992.

The History Guy, "The 1947 Centralia Mine Disaster" (video), September 6, 2021.

Illinois Coal Mines, Miners & Railroads (Facebook group)

John H. Keiser, "The Union Miners Cemetery at Mt. Olive, Illinois: A Spirit-Thread of Labor History", Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908–1984), Vol. 62, No. 3 (Autumn 1969), pp. 229–266.

Mary Delach Leonard, "For Illinois homeowners worried about mine subsidence, here's a map that locates coal mines", St. Louis Public Radio, September 17, 2017.

Frank Masters, “No. 5 Mine” Distillery, Macoupin County ILGenWeb.

Joe Millitzer, Kevin S. Held, Rebecca Roberts, Homes evacuated over Benld mine collapse, Fox 2, April 8, 2015.

Mythic Mississippi Project, PMA (Progressive Miners of America) union.

Jennifer M. Obrad & C. Chenoweth, Directory of Coal Mines in Illinois 7.5-Minute Quadrangle Series Bunker Hill Quadrangle Macoupin County, Institute of Natural Resource Sustainability, Illinois State Geological Survey, 2010.

Pamela J. Richart, "History of Illinois Coal Mining", Eco-Justice Collaborative, January 8, 2022.

Harold R. Rauzi, Coal Mines on the Prairie: The Life of an American Community, Cleveland Heights, Ohio, 2019.

Retired Members of UMWA Local 1613, Coal Mining and Labor in South Central Illinois, The Mother Jones Museum at Mount Olive, Illinois, October 2020.

SangamonLink, "Coal Mining", History of Sangamon County, Illinois, April 10, 2013.

Photos: A look at coal mining in Southern Illinois history, "Photos: A look at coal mining in Southern Illinois history", The Southern Illinoisan, June 13, 2022.

Wikipedia, "Battle of Virden".

Wikipedia, “Cherry Mine Disaster”.

Wikipedia, "Union Miners Cemetery".

Fascinating.

Very interesting article, thank you. My great grandfather died in an Illinois mining accident in 1922. From the archives: “KEIL

September 12, 19224, Tuesday, Matt Keil, of Tamaroa, mine manager, age 48 years, married, died from injuries received six days previous in Kuhn Coalery Company's mine [DuBois, Washington County, Illinois]. The mine had been closed about one year and preparations were being made to start operating. Deceased was at shaft bottom and stepped across the cage to start a pump which was about six feet from the cage, while thus engaged the cage without his knowledge was taken away and in attempting to cross back, he walked into cage seat, which was about 3½ feet deep in water that had been heated by exhaust from pump. He was so badly burned that he died as stated above. He leaves a widow and three children.”