Forged in Rebellion: Organized Labor in Central Illinois Coal Mines

Part 2 of the history of the industry that powered St. Louis

Welcome back to Unseen St. Louis and our two-part exploration of the early Illinois coal industry. In Part 1, we followed the rise of Illinois’s coal empire — from exposed riverbank seams to boomtowns like Benld and Gillespie, and what it was like to work in a coal mine in the late 19th and early 20th century.

The story of coal mining in Illinois wasn’t just about digging coal — it was also about standing up for workers’ rights and better (and safer) working conditions. In this second part of my story of Illinois coal mining, we’ll explore how miners struggled to get fair pay and better working conditions from the mine owners, leading to several violent clashes. Out of that early unrest, the United Mine Workers of America emerged in 1890, offering solidarity and strength in numbers. But in the coalfields of Illinois, where workers had a long memory and a rebellious streak, loyalty to the national union didn’t always last. By the 1930s, frustrated miners broke away — and the coalfields erupted once again.

A union rises from the dust

By the 1890s, coal mining in Illinois was booming — but for the miners who did the digging, the conditions were brutal. Underground, as discussed in part one, they performed backbreaking work under dangerous working conditions. Above ground, many lived in company towns, paid in company scrip, and were locked into debt by company stores. There were no safety standards, no compensation for injuries, and no consistent wages — miners were often paid by the ton or the carload, and disputes over short weights were common.

It was out of this grinding exploitation that the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) was born in 1890, merging several earlier labor organizations. The union’s early goals were straightforward but revolutionary: an eight-hour workday, fair pay, an end to child labor, safer conditions, and collective bargaining power. At first, the UMWA’s presence in Illinois was minimal — fewer than 400 miners statewide were organized. But southern and central Illinois were fertile ground for rebellion.

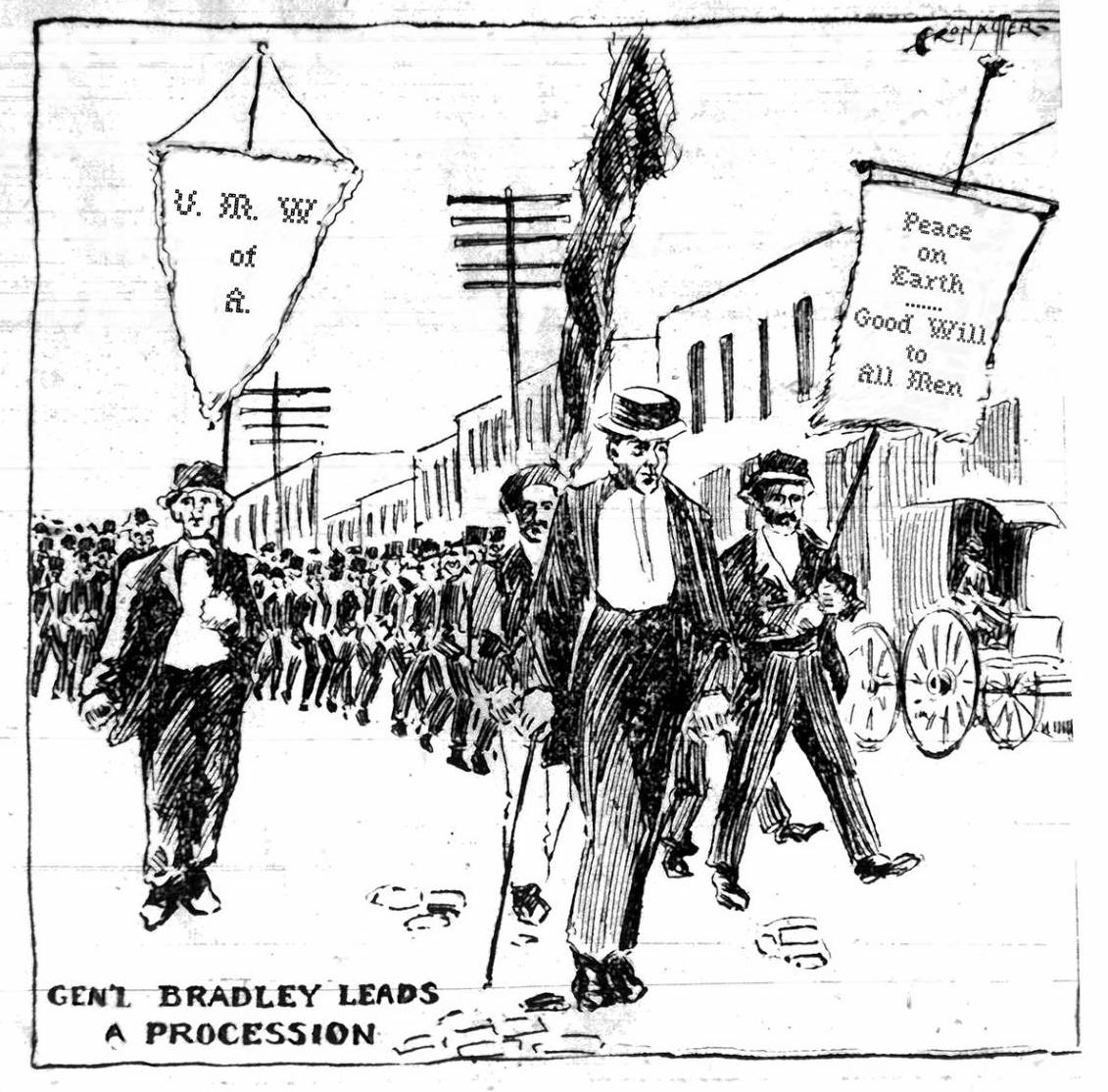

By 1897, those seeds took root. That summer, the UMWA called for a national strike. In Illinois, union membership stood at fewer than 400 — until a charismatic thirty-one-year-old miner from Mt. Olive stepped forward. His name was Alexander Bradley. Declaring himself “General” Bradley, he donned a Prince Albert coat and a silk top hat, becoming the instantly recognizable face of labor in the Illinois coalfields.

Bradley was no ordinary organizer. An English immigrant who began mining at the age of nine, he led marches across central Illinois, giving fiery speeches and forbidding violence. His dramatic flair, coupled with deep credibility among working miners, helped ignite a movement. Under his leadership, the union grew rapidly. By year’s end, UMWA membership in Illinois had exploded to more than 30,000. Bradley and the UMWA welcomed miners regardless of language or origin, uniting European immigrants with native-born workers under a common cause.

In 1897, the UMWA negotiated a landmark contract with numerous coal operators that secured an eight-hour workday, improved working conditions, and enhanced safety standards. But not all coal companies were willing to recognize the union’s authority, leading directly to the infamous Battle of Virden.

The Battle of Virden

On October 12, 1898, the quiet town of Virden, Illinois, became the site of one of the most violent labor confrontations in American history — a clash that revealed the deep fractures between coal companies and organized labor, and between white miners and Black strikebreakers.

The trouble began when the Chicago-Virden Coal Company, refusing to honor a union agreement with the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), decided to import African-American laborers from Birmingham, Alabama, to break the strike and reopen the mines. These Black miners were not told they would be strikebreakers. Instead, they were led to believe that the regular miners had left their posts to fight in the Spanish-American War.

Anticipating trouble, the coal company constructed a fortified stockade around the mine and hired heavily armed guards from the Thiel Detective Agency in St. Louis. It was clear they were preparing for a fight.

Meanwhile, miners from across central Illinois — including a large contingent led by Gen. Bradley — gathered in Virden to resist what they saw as an existential threat to the union.

At 12:40 p.m. on October 12, a northbound train carrying over 100 Black men and their families — along with Thiel guards — pulled into Virden. When the train neared the stockade, gunfire erupted. No one knows who fired first, but soon both miners and guards were shooting. The guards, protected by the stockade and armed with modern Winchester rifles, had the advantage. The miners returned fire with shotguns and hunting rifles.

The shootout lasted ten minutes. Seven miners and five guards were killed, and at least forty strikers were wounded. Remarkably, none of the Black strikebreakers were injured, as the train never stopped. Its engineer, wounded in the exchange, continued on to Springfield, refusing to unload the strikebreakers into the chaos.

In the aftermath, the Illinois National Guard arrived hours too late to prevent the violence. Governor John Tanner, who had previously warned the mine owners that bringing in replacement workers would provoke bloodshed, banned further imports of strikebreakers into the state. He even threatened to use Gatling guns to stop any more trains from crossing the line.

The Battle of Virden was a flashpoint. It showed the world the brutal tactics coal companies were willing to use and organized labor’s unwillingness to back down. While the UMWA was founded as an integrated union, the events at Virden — and elsewhere in southern Illinois — also resulted in a decades-long setback for Black coal miners. Though some strikebreakers later joined the union, many were driven out by white miners under the influence of racial division and, later, Ku Klux Klan agitators.

Ongoing labor struggles and racial violence

For many years following Virden, there were small-scale clashes between mine workers and coal mine companies — as well as between rank and file miners and the UMWA leadership — that would eventually erupt in what became known as the Illinois Mine Wars, a series of violent clashes between union miners, coal companies, strikebreakers, and sometimes each other.

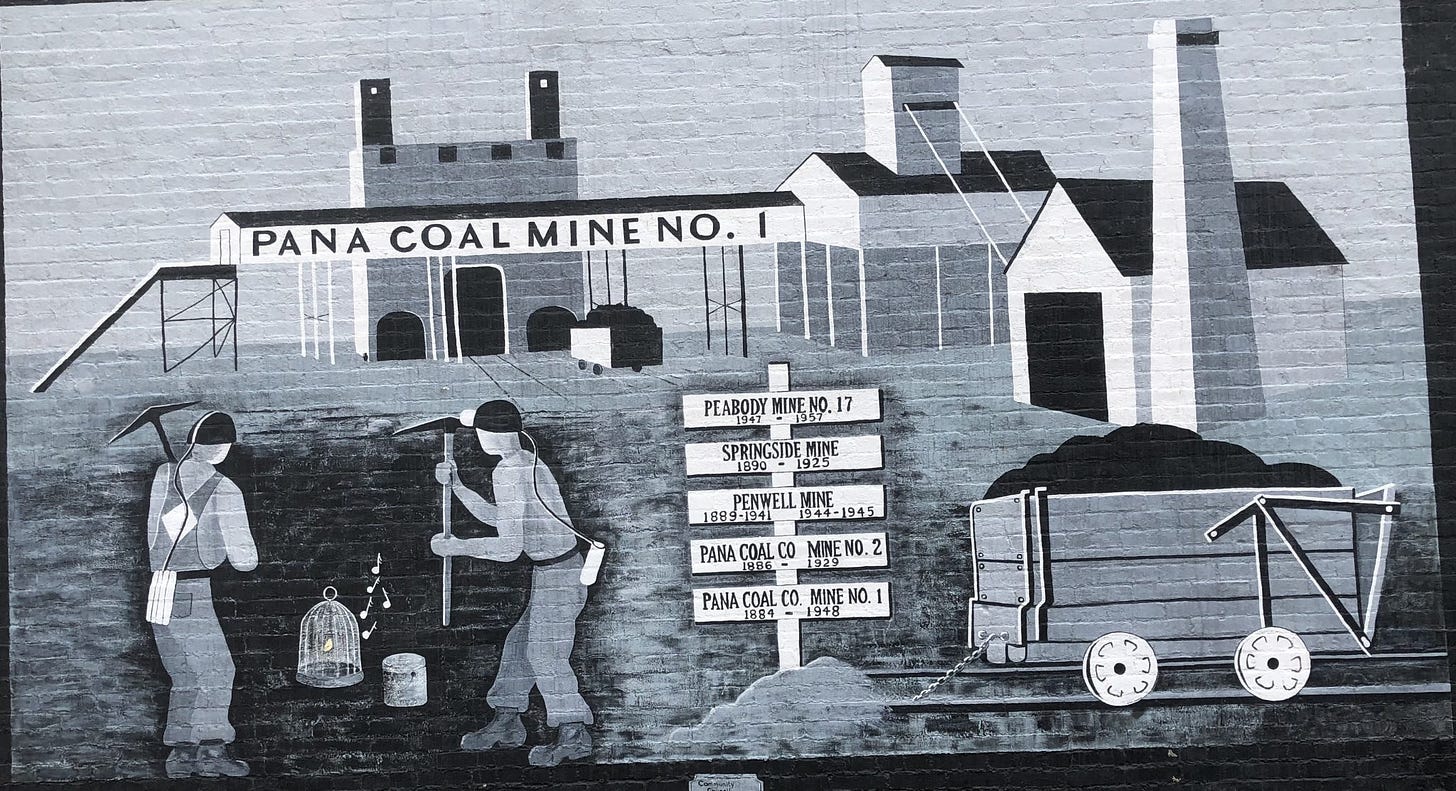

Another violent episode similar to Virden took place in Pana, a small coal town southeast of Springfield. Tensions had been simmering since 1898, when the coal company brought in Black mine workers recruited by labor agent T.J. Rhodes. Governor John Tanner initially deployed the National Guard to keep the peace, but when the troops were withdrawn in March 1899, violence once again exploded. On April 10, 1899, a gunfight left seven Black miners and one white union miner dead. The violence in Pana prompted a congressional investigation and brought national attention to the deep racial and labor tensions in the state.

Other flashpoints followed. In Carterville, in 1899 and again in 1903, union men attacked Black miners with deadly results, spurred on by resentment and the coal companies’ ongoing efforts to divide the workforce. These events revealed a painful contradiction in the labor movement: companies exploited racial divisions to weaken strikes — and sometimes the unions themselves fell short of defending Black workers equally.

From discontent to defiance in Macoupin County

By the early 1930s, coal miners in towns like Gillespie, Benld, Mt. Olive, Staunton, and Carlinville had become a formidable force within the labor movement — not just organized, but openly defiant. Disillusioned with the increasingly autocratic leadership of UMWA president John L. Lewis, they began to question the union’s direction. Here in Macoupin County, miners didn’t just grumble — they prepared to take matters into their own hands.

Local miners had fought hard through District 12 to win the highest wage scale in the nation — $7.50 per day — only to see their gains erased by successive wage cuts. When Lewis forced through another cut in 1932, slashing pay to just $5.00 a day despite an overwhelming rejection by the miners, outrage boiled over. Many in Macoupin viewed the move not just as a betrayal, but as the final insult in a long pattern of disregard.

That betrayal had roots stretching back to 1929, when Lewis revoked District 12’s charter and installed loyalists in place of elected local officers. Although a legal compromise was eventually brokered, the damage had already been done. Macoupin miners had a long memory and a fierce sense of local autonomy, and many were already discussing the possibility of breaking away.

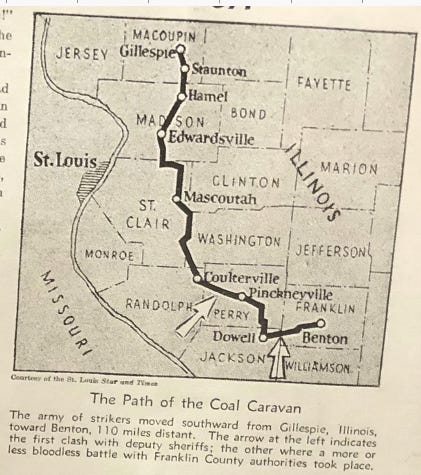

The final spark came in 1932, when miners accused Lewis’s operatives of tampering with ballots during a contract referendum. Furious and determined, miners across Macoupin County organized a mass caravan of more than 800 cars and trucks and set off southward in August to rally fellow miners in Franklin County. But just outside Mulkeytown, the caravan was met by a blockade of sheriff’s deputies and police, who opened fire on the unarmed procession. Over 100 miners — including women and children — were injured.

The ambush at Mulkeytown was the breaking point. To many miners, it wasn’t just an act of violence — it was a betrayal. They believed the UMWA had sided with the coal operators to crush dissent and push through a contract they had overwhelmingly rejected.

Stunned and furious, they returned home and took decisive action. Fed up with wage cuts and the autocratic rule of UMWA president John L. Lewis, thousands of Illinois miners decided it was time for a new direction. Nearly 300 delegates gathered on September 1, 1932 at the Colonial Theater in Gillespie to form a new union: the Progressive Miners of America (PMA), later renamed the Progressive Mine Workers of America in 1938. They rejected Lewis’s centralized control and top-down decision-making, calling instead for democratic leadership, transparent negotiations, and militant solidarity. Within weeks, miners at all four Superior Coal Company mines in Macoupin County voted unanimously to leave the UMWA, and by November, the PMA had gained dominance throughout Macoupin, Montgomery, Madison, St. Clair, Sangamon, and Christian counties..

Shortly after the PMA’s formation, the Women’s Auxiliary of the Progressive Miners of America was created. Many of the women who had ridden to Mulkeytown alongside the striking miners — only to be injured and denied medical care — returned home just as radicalized. On November 2, 1932, 157 delegates from 38 auxiliaries convened and officially launched their own democratic, elected organization to support the new union. Their first president, Agnes Burns Wieck, helped lead an effort grounded in mutual aid, solidarity, and activism. These women organized rallies, raised funds, and tended the wounded. They understood that women were full partners in the struggle for a decent life.

Illinois Coal Wars

Major coal companies, such as Peabody Coal, refused to recognize the PMA, sparking an ongoing, bitter, and often violent conflict in the 1930s known as the Illinois Coal Wars. Jurisdictional clashes between UMWA loyalists and PMA miners escalated into bombings, shootings, beatings, and arson. Businesses and homes were attacked. Many immigrant miners — especially in towns like Benld, where PMA leadership was strong — bore the brunt of the violence. The federal government eventually indicted dozens of PMA members under anti-racketeering laws — the first time such charges were used against a labor union members.

Lewis denounced the PMA as a “dual union” and accused its members of communist sympathies. But for those who had risked everything at Mulkeytown and elsewhere, the PMA represented the true voice of the rank and file.

In 1937, 540 miners in Wilsonville staged the nation’s first coal mining sit-down strike at Superior Mine No. 4, demanding a work-sharing agreement following layoffs at nearby Mine No. 1. For nine days, they remained underground, drawing national media attention. Though PMA leadership disavowed the unauthorized strike, sit-down strikes became a widespread labor tactic for years afterward.

Despite its limited geographic reach and eventual decline, the PMA left an indelible mark. Gillespie and Benld became hubs of union activity, hosting mass meetings and honoring fallen “martyrs” in monuments and publications. The PMA officially dissolved in 1999, but its legacy endures as a powerful chapter in working-class defiance, born in the coalfields of Macoupin County.

Union Miners Cemetery and the spirit of Mother Jones

In the quiet town of Mount Olive, in Macoupin Co. Illinois, lies a piece of hallowed ground unlike any other in the United States — the Union Miners Cemetery, the only union-owned cemetery in the nation.

The cemetery was born from the aftermath of the Battle of Virden. Four of the fallen miners were from Mount Olive. But when their bodies were returned home, they were refused burial in the city cemetery and again by the local Lutheran church, whose leaders considered them “murderers” rather than martyrs. The coal companies’ influence extended even to the grave.

Rather than accept this indignity, the local union took action. At the urging of labor organizer Adolph Germer, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) purchased a one-acre plot on the outskirts of town. In 1899, the Union Miners Cemetery was established as a final resting place for the Virden martyrs — a space controlled not by corporations or churches, but by the workers themselves. Over the years, it expanded to include not only more graves but monuments to fallen miners, union leaders, and the struggles of the labor movement. In 1932, Mount Olive’s UMWA locals — 728 and 125 — took steps to transfer ownership of the cemetery to the newly formed PMA. Thus, the cemetery became a tangible symbol of the break from Lewis and the beginning of a new, democratic labor movement.

The cemetery’s most famous resident is Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, one of America’s most revered labor organizers. A fierce advocate for miners, Mother Jones was touched upon hearing about the violence at Virden and by her visits to the cemetery to honor the fallen miners. Years later, she would request to be buried in the cemetery. In her words:

“When the last call comes for me to take my final rest, will the miners see that I get a resting place in the same clay that shelters the miners who gave up their lives on the hills of Virden… I hope it will be my consolation when I pass away to feel I sleep under the clay with those brave boys.”

Her wish was honored when she died in 1930 at the age of 100. Her grave, marked by a grand monument erected in 1936, remains the cemetery’s centerpiece. At its dedication, more than 50,000 union members and families gathered to pay tribute.

Today, the cemetery still stands — a testament to a time when coal miners dared to fight not just for better wages, but for dignity, democracy, and remembrance. Plaques and monuments throughout the grounds commemorate “General” Alexander Bradley, the fallen of Virden, and twenty-one other labor martyrs. Each October 12, Miners Day is observed at the site, keeping alive the legacy of sacrifice and unity.

To walk among the graves at Union Miners Cemetery is to walk through the heart of Illinois labor history — and to hear, in the wind through the pines, the whisper of Mother Jones: “Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living.”

They fought like hell

The mines are quieter now. The towns that once pulsed with union rallies and coal trains have grown still. But the legacy of Illinois coal — and the radical defiance it sparked — remains embedded in the land and in the stories we carry. From Mulkeytown to Mount Olive, this isn’t just a story of decline — it’s a testament to the workers who stood their ground and changed the course of labor history. And here in St. Louis, we owe them more than memory. The coal they pulled from the ground powered our factories, lit our homes, and fueled our rise as a major American city. The rights many of us take for granted today — from the eight-hour day to workplace safety — were forged underground by miners who demanded something better, not just for themselves, but for all of us.

If you enjoyed this two-part series on Illinois coal miners and organized labor, please consider sharing it with a friend. And if you value the work I do on Unseen St. Louis, please consider subscribing or upgrading to a paid subscription. And above all else, thank you for your support.

Sources

Jim Alderson, Illinois Coal Museum at Gillespie.

Jeff Biggers, “Oct. 12, 1898: Battle of Virden“, Zinn Education Project.

Abigail Bobrow, "Built on Coal", Storied Magazine, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, October 4, 2021.

Casey Bischel, "Coal mining has deep history in Southern Illinois", The Register-Mail (Galesburg), January 8, 2018.

Coal Mining and Labor in South Central Illinois, The Mother Jones Museum, Mt. Olive, IL.

Terri Dee, "Abandoned IL coal mines pose health, environmental complications", WSIU Public Broadcasting, June 24, 2024.

Rosemary Feurer, Remember Virden! The Coal Mine Wars of 1898-1900, Illinois Periodicals Online

"First Coal Mine in Illinois", Southern Illinois Tourism, Jackson County, Illinois.

“General Alexander Bradley,” Mythic Mississippi.

“General Bradley,” Mother Jones Museum, Mt. Olive, IL.

Dwyer Gunn, "A Look Inside the Coal Communities in the Illinois Basin", Pacific Standard, July 2017.

Mara Lou Hawse and Dianne Throgmorton, Tell Me a Story: Memories of Early Life Around the Coal Fields of Illinois, Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, 1992.

The History Guy, "The 1947 Centralia Mine Disaster" (video), September 6, 2021.

Illinois Coal Mines, Miners & Railroads (Facebook group.

John H. Keiser, "The Union Miners Cemetery at Mt. Olive, Illinois: A Spirit-Thread of Labor History", Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908–1984), Vol. 62, No. 3 (Autumn 1969), pp. 229–266.

Mary Delach Leonard, "For Illinois homeowners worried about mine subsidence, here's a map that locates coal mines", St. Louis Public Radio, September 17, 2017.

Mining Artifacts & History, Mining Artifacts & History.

Mythic Mississippi Project, PMA (Progressive Miners of America) union and Black Miners.

"Photos: A look at coal mining in Southern Illinois history", The Southern Illinoisan, June 13, 2022.

Pamela J. Richart, "History of Illinois Coal Mining", Eco-Justice Collaborative, January 8, 2022.

Harold R. Rauzi, Coal Mines on the Prairie: The Life of an American Community, Cleveland Heights, Ohio, 2019.

Retired Members of UMWA Local 1613, Coal Mining and Labor in South Central Illinois, The Mother Jones Museum at Mount Olive, Illinois, October 2020.

SangamonLink, "Coal Mining", History of Sangamon County, Illinois, April 10, 2013.

Sit-down in Wilsonville, Minewar.org.

Wikipedia, "Battle of Virden".

Wikipedia, “Cherry Mine Disaster”.

Wikipedia, “Pana Riot.”

Wikipedia,"Union Miners Cemetery".

My Italian great grandfather was a Progressive Miner and my great grandmother was in the auxiliary. Both Italian immigrants living in Benld. My mom remembers the auxiliary women in their white uniforms making Fiadoni (baked cheese puffs from Abruzzo) for their meetings. My grandfather of Irish ancestry worked for the United Mine Workers. He thought John Lewis was a hero, my great grandfather thought he was the devil. He died never knowing his son-in-law was a UMWA man.