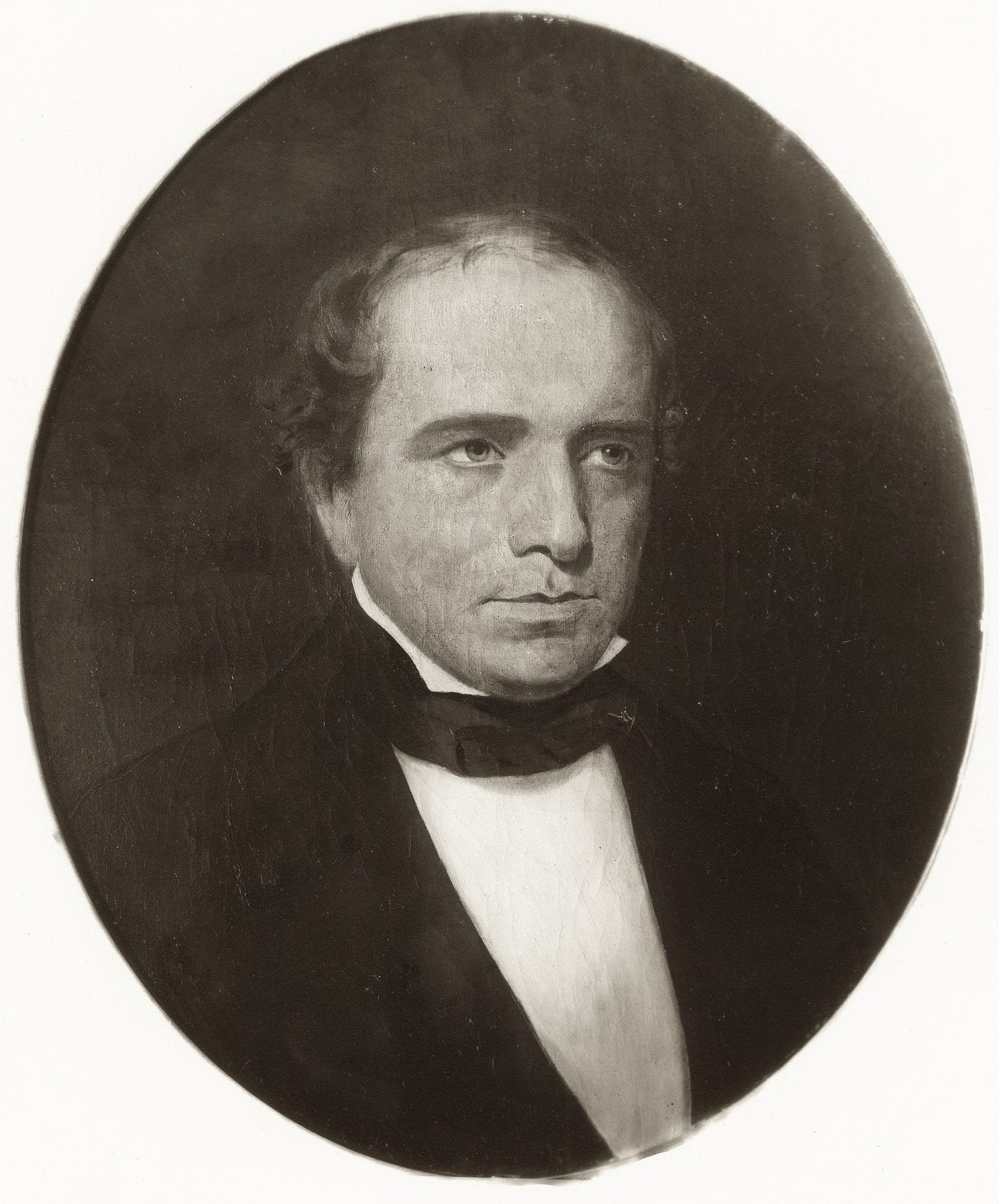

Bryan Mullanphy: 'A man of many peculiarities’

Exploring the life of the eccentric and inspiring man who was St. Louis' 10th mayor

Bryan Mullanphy might not be a household name, but he may be one of the most underappreciated historical figures in St. Louis history. For this special St. Patrick’s Day edition of Unseen St. Louis, let’s examine the story of a remarkable Irish-American who had a significant impact on our city’s history.

I first stumbled across the story of St. Louis’s 10th mayor, Bryan Mullanphy, while working on another project. Since then, the more I’ve read about him, the more obsessed I’ve become with uncovering details about him. A loner for most of his life, he lived on his own terms, modeling kindness, generosity, and a commitment to justice that make him worthy of remembrance.

This introductory article serves as a gateway to Bryan Mullanphy's story, laying the groundwork for future articles I hope to write that will go into more detail about his life and the world of pre-Civil War St. Louis. (It’s also the product of ongoing research, and I’m learning more literally every day.)

Having said that, let’s get started!

The Mullanphy clan

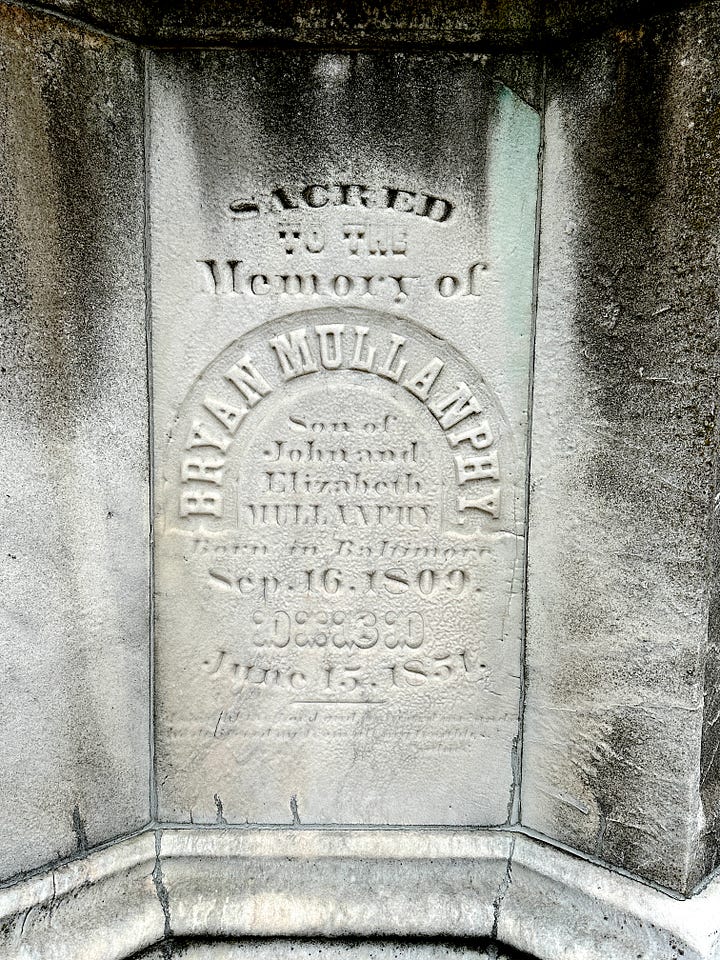

Bryan Mullanphy, born in 1809 in Baltimore, was the only surviving son of John and Elizabeth Mullanphy, Irish immigrants who arrived in the US in 1794, seeking a brighter future than what the Penal Laws afforded Catholics back in Ireland.

John and Elizabeth lived in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and possibly elsewhere, before John ventured into commerce as a merchant in Frankfort, KY. Encouraged by Charles Gratiot, John first visited St. Louis in 1804, discovering it was a city that, due to its Spanish and French origins, welcomed Catholic immigrants from the beginning. John's fortune soared when he bought cotton at 4 cents a pound, which, after being requisitioned by Andrew Jackson for the War of 1812 and subsequently returned, he sold in Liverpool for 30 cents a pound. After John’s brief service to Jackson in the war, the Mullanphys made St. Louis their new home.

John’s windfall and subsequent investments enabled him to purchase sizable amounts of land in the city and become a well-respected Catholic leader within the community. Among other things, he helped to start local banks and contributed to the establishment of St. Louis College, soon to become St. Louis University.

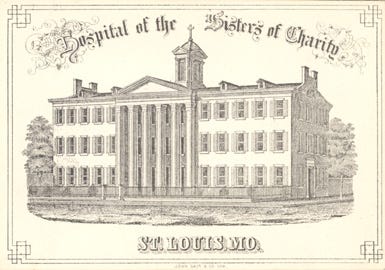

He also established the Sisters of Charity Hospital (later known as the Daughters of Charity, then Mullanphy Hospital, and eventually, De Paul), the first Catholic hospital in the US.

John Mullanphy's estate, valued at between $3 and $4 million and encompassing over a thousand acres of land across the city and county, established him as St. Louis's first millionaire.

Bryan Mullanphy, the only son among seven surviving children, grew up in a family where his sisters also led notable lives. Ellen joined a religious order in France, while the others married wealthy and noteworthy men. In particular, Jane Mullanphy married former Irish rebel Charles Chambers, and John gave the couple the Taille de Noyer house in Florissant. Ann became the wife of Thomas Biddle, who met his end in a duel on Bloody Island. And Eliza married James Clemens Jr., a cousin of Samuel Clemens and the man who built the Clemens mansion that tragically burned in 2017.

The shaping of a gentleman

Education was paramount in the Mullanphy household. John, who would later have over 1000 books in his St. Louis home, ensured his daughters were educated by sending them to convent schools, and sent Bryan (at the age of 9) to a Jesuit school in Paris, followed by Stonyhurst College (a Catholic boarding school) in England.

As a boy, Bryan tried to please his father, taking all the required classes and excelling academically. John's vision for Bryan was for his son to become a refined gentleman, skilled in languages, the arts, and social decorum. Bryan indeed became well-educated, mastering French, acquiring proficiency in several other languages, and nurturing talents in drawing and music. Attorney William Van Ness Bay, who would become a friend and colleague later in life, noted, “It was impossible to converse with [Bryan] on any subject which had not elicited more or less of his attention.”

Letters from the time show Bryan was an exemplary student who nevertheless yearned for home. When he finished school in 1827 at the age of 18, he headed to St. Louis. As was common, he sailed to the port at New Orleans and took passage on a steamer for St. Louis. As Bay described, Bryan ran into a bit of difficulty on his final leg of travel.

“On reaching a point about fifteen miles below the city, the boat was prevented from proceeding further by floating ice, and the passengers were forced to land and proceed to the city by any conveyance they could obtain. At that time we had no macadamized roads, and the mud was knee-deep from recent rains. Bryan hired a mule, and rode bare-back to the city, and when he reached the family residence he was covered with mud from head to foot, presenting a most deplorable sight. Upon the announcement of his arrival, his father came to the door to welcome him home, but instead of the polished and fine-appearing gentleman which his long-cherished hopes had led him to anticipate, he saw a man clothed in mud and mire, and, according to tradition, expressed his displeasure and disappointment.”

From what I can gather, this wasn’t the first time John Mullanphy was displeased with his son's behavior. An 1878 article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described how Bryan “had not realized his [father’s] expectations of brilliancy.”

At any rate, John’s passing in 18331 must have been a bit of a relief to the young Bryan, who was then free to chart his own future.

A perpetual bachelor

Despite being the only son of one of the city's wealthiest and most influential figures, Bryan remained unmarried, something that would have been unusual for the time.

To explain his bachelor status, Bryan told his friends the following story. As a young man, he had developed a fondness for a young German girl. Deciding to propose, he put on his best suit, hired a horse and buggy, and set off to her home. Along the way, he spotted a horseshoe. Taking it as a sign of good luck, he stopped to pick it up and continued on his way. Upon reaching the girl's home, he was asked to wait inside by a servant as the woman had another caller. Bryan took a seat, only to hear the woman speaking to a man, and the two were making fun of him! Naturally, Bryan chose to leave right then and there, sparing himself further embarrassment. He never crossed paths with the woman again, and from that point on vowed to remain unattached.

Inordinate self esteem

As an adult, Bryan was a man of “medium size; rather heavy set, not very large, but robust,” according to his friend, fellow attorney and politician John Darby. Several people noted that although not a great orator, Bryan spoke clearly and with a slight Irish brogue. Irish immigrant Flora Byrne, living in Baltimore, writing to her sister, described Bryan as the “little judge” and a “precious little person” whose only fault was “inordinate self esteem.” Contemporaries noted his skill at drawing, especially caricatures. His friend Bay described Bryan’s “carelessness in dress” and how, in his interactions with others, Bryan could sometimes be abrupt or discourteous. Despite all that, Bay noted that “under that rough exterior [Bryan] carried a heart that overflowed with kindness and benevolence.”

It’s clear that Bryan was eccentric and lived life as he pleased. Remarkably, he was known to wander the streets of St. Louis playing his banjo. Darby described how Bryan “used to go around the country making speeches, and his eccentricities and peculiarities were such as always to attract attention.”

Theater escapade

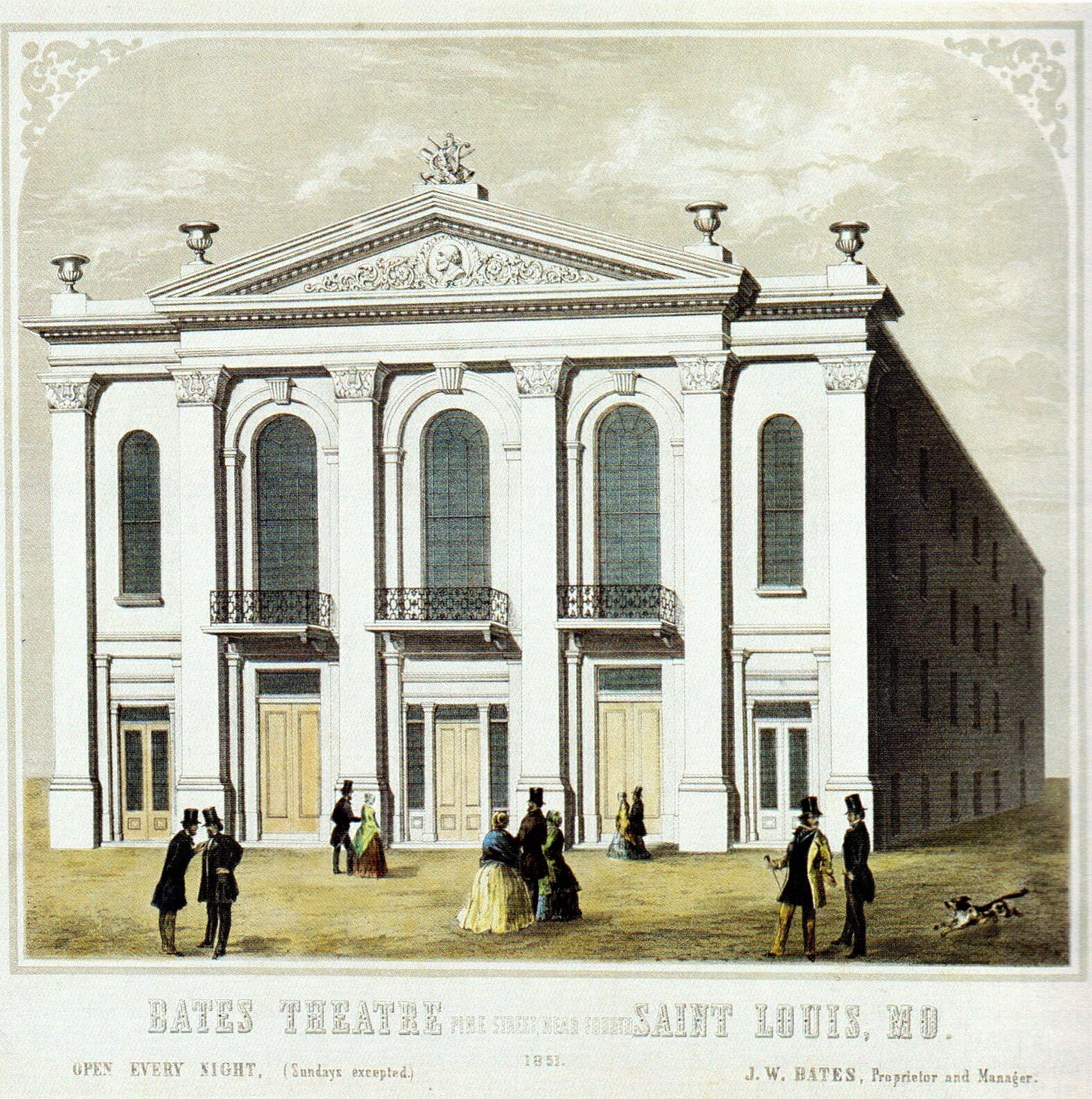

One of my favorite stories about Bryan gives a good glimpse into his character. This tale, detailed by both Darby and Bay, involved an outing Bryan went on in 1850 with his friend George Jamison, a lead actor at Bates Theater.2

Bryan stopped by the Planters' House (a hotel that was across the street from the Courthouse) to invite Jamison for a ride out into the country. After riding in a buggy for 10 to 12 miles outside St. Louis, they paused at a saloon for wine. There, the two men had a disagreement, leading Bryan to quip that if Jamison “could use his limbs as well as he did his tongue, he would get home before morning.”

As dusk approached, Bryan sped off in his buggy, leaving Jamison stranded. With a play pending that evening, Jamison had to rush to find new transportation to return to the theater. He arrived half an hour late, with the theater manager attempting to excuse his absence to the audience. Despite the incident, Bryan apparently forgave his friend, as he encouraged Jamison to join him on another outing to Florissant just a few days later.

Peculiar defender of freedom and fairness

After completing his law studies at St. Louis College, Bryan began practicing as an independent lawyer by 1830. He had a reputation for fairness, particularly in his commitment to representing cases that would not oppress the poor.

It didn’t take long for Bryan’s sense of justice to be tested. On July 21, 1836, Bryan was an Alderman for the city when Elijah Lovejoy wrote an editorial in the St. Louis Observer condemning Judge Luke Lawless's refusal to convict anyone for the lynching of free Black man Francis McIntosh. In response, a mob attacked the Observer’s office while the city watch stood by and did nothing. In the midst of the chaos, and despite Lovejoy's clear anti-Catholic stance, Bryan was the only city official who attempted to stop the mob and safeguard Lovejoy's printing press. Despite Bryan’s efforts, the mob destroyed the press, throwing its remnants into the Mississippi River. (Lovejoy relocated to Alton, IL, but was murdered a little over a year later).

This dedication to justice continued when Bryan was appointed judge for the Eighth Judicial Circuit Court of Missouri from February 1841 to March 1844.

During his tenure as a judge, Bryan presided over several significant freedom suits filed by enslaved individuals seeking liberation, freeing them on at least a few occasions. In particular, the case of Lucy Delaney stands out. Delaney's memoir vividly recounts a moment in her trial where, after being previously neglected by the court and forced to remain imprisoned for over a year, her attorney, Edward Bates, insisted on her immediate release before proceeding with any other matter. As the judge in the case, Bryan concurred with Bates's request. This decision not only marked a critical point in Delaney's life but also highlighted Bryan’s role in the broader struggle for freedom within the judicial system of the time. It is noteworthy that freedom suits were not as successful after Bryan stepped down from the bench in 1844.3

Having said all of this, his personal position on slavery has been difficult to determine. I’ve seen nothing to suggest Bryan was an abolitionist, and it’s clear that his parents, and most or all of his siblings, owned slaves. According to probate records, at his death Bryan owned a single family of enslaved people, but I don’t know where they would have lived or how he would have benefited from their labor, given that he lived most of his adult life in a hotel or a small apartment. My current guess is he may have inherited them from his father, but they lived with one of his siblings, but this bears further research.

Bringing the St. Vincent de Paul Society to America

Moved by the challenges faced by immigrants in St. Louis, Bryan was instrumental in establishing many efforts to assist the Irish and the poor in St. Louis. His most significant effort was helping bring the St. Vincent de Paul Society to the United States. The Society, originally founded in France in 1833 by Frederic Ozanam, aimed to assist the poor through personal service and spiritual growth, providing immediate relief to those in need, regardless of their race, nationality, or religion, a principle that continues to guide its operations today.

Inspired by Ozanam’s mission, Bryan, along with key figures like Dr. Moses Linton and Father Ambrose Heim, sought to replicate this charitable work in St. Louis, forming the first Society of St. Vincent de Paul conference in the U.S. at the Old Cathedral. The Society's Conference in St. Louis gained formal recognition on February 2, 1846.

Challenging tenure as mayor

Bryan Mullanphy, running as a Democrat, was elected as the Mayor of St. Louis in 1847. His one-year term was marked by significant challenges for the city, including a sharp increase in the population due to German and Irish immigrants escaping famine and political upheaval in their homelands. This surge in immigration led to heightened anti-Catholic sentiment and political strife from the Know-Nothing Party. The city also faced rapid expansion in commerce and industrialization.

From the start, Bryan’s leadership style caused conflict with other officials. His initial plan to include members outside the Democratic Party within the city government caused a stir and alienated him from the Aldermen, who refused to accept his nominees. Furthermore, his cautious financial philosophy led him to advocate a "pay as you go" policy to avoid debt, emphasizing the city's independence from unreliable banks—a perspective shaped in part by his election to Director of the Bank of the State of Missouri in 1838. His stance resulted in him turning down several proposals from the City Council, which, in response, led them to dismiss many of his own suggestions.

St. Louis faced rising crime rates, exacerbated by river traffic and burgeoning commerce. In response, the city enacted a strict vagrancy ordinance in 1845, which Mullanphy, well-versed in the law, selectively enforced, recognizing the impact poverty had on the city. Such a position did not reassure other members of the city government. Meanwhile, he attempted to improve city infrastructure, notably advocating for the macadamization of Gravois Road to facilitate coal transportation, a project the city refused to fund.

Cholera was a significant concern for Mullanphy, who had witnessed many die from previous outbreaks. He described cholera as “the terrible disorder that ravages our city” in a letter. With a basic understanding of the disease's transmission through contaminated sources already emerging, Mullanphy urged city officials to clean up the city and drain Chouteau’s Pond. This pond, created early on by damming Mill Creek for a flour mill, had become a polluted eyesore as the city's population and industrial activities grew. But again, his calls for action were ignored by the city.

Helping immigrants

Unlike many of the other men of wealth and privilege, Bryan demonstrated a true concern for the city's newcomers, especially the destitute Irish immigrants who had been streaming into the city in large numbers beginning in 1847 as the potato crops failed.

According to John Darby, one of Bryan’s favorite activities was to stand on the Mississippi River wharf and watch the riverboats come in from New Orleans. As Darby described it, “so touched would he be at the site of the ragged, homeless wanderer from across the ocean he would have the boat purser detain them, while he went to his banker.” Bryan would then hand out money to everyone, including the crew and stevedores who unloaded the cargo.

Many of these people ended up in the Kerry Patch, a neighborhood that sprang up on his sister Ann Biddle's land. It was named for the county in the West of Ireland from which many of the Irish came, often only speaking Gaelic, making their assimilation more difficult. Ann allowed the Irish newcomers to squat on her land and build makeshift shanties, turning it into a makeshift haven for those who had nowhere else to go.

Bryan and his sister would regularly visit the Patch to hand out money and supplies, including an often-recounted tale about Bryan purchasing 300 razors from a local shop so that these new immigrants could shave.

Claims of insanity

After his term as mayor ended in 1848, Bryan continued working as an attorney until his untimely death on June 15, 1851. However, those final three years seemed to have been particularly difficult for him.

During this period, his mental health took a turn for the worse. In early 1849, Bryan was hospitalized at the Sisters of Charity—the institution founded by his father. In a few letters written between family members and attorneys during this period, there are references to his “unsound mind” and potential insanity, as well as discussions about appointing a guardian to take charge of his estate and a hearing to determine his competency. What exactly had happened with Bryan remains unclear as none of this correspondence provided specifics.

Despite his family’s fears that he would never recover or return to a normal life, apparently, he did. By the summer of 1849, he was back out in the city. Among other things, he visited an attorney to draft his will, went out with his actor friend as noted above, considered a second run for mayor in 1850, and established the Mullanphy Law Library Association. For reasons that aren’t clear, despite his status and wealth, during this period he lived in a modest apartment over a shop, a residence that in the city directories had been occupied by clerks and a widow just prior to and after his own time there.

Victim of cholera

On the morning of June 15, 1851, Bryan’s brother-in-law, James Clemens Jr., wrote a letter to his wife, Eliza, conveying sad news.

In the letter, he wrote:

“[Bryan] was attacked with cholera about 4 o’clock yesterday at the Missouri Hotel and what you have expected and prepared to hear any morning for the last two months has happened but not by any means as bad as you calculated it would be… sensible for a short time before he expired he said to Father Dolman that he was sorry for his treatments to the family… [because] he had determined on self-destruction we have the consolation to know that he died in an hour, on a bed with part of his family around him and not in the street as one expected, unattended and uncared for and alone.”

It is an unusual and uncomfortable letter, as much for what it says as for what it doesn’t. As noted above, Bryan had been hospitalized two years earlier for an undisclosed mental health issue. The exact reasons for Bryan’s apology on his deathbed—or why the family feared he might die alone on the streets—are not detailed.

But there are a few clues as to what form his “self-destruction” may have taken. A newspaper of the period alluded to his ‘dissolute’ lifestyle—at the time, this term generally referred to drunkenness. In 1844, before becoming mayor, Bryan had addressed the St. Louis Total Abstinence Association about the virtues of sobriety, which suggested he may have had personal experience with excessive drinking. Following his demise, his family contested his will but later withdrew, with the suggestion that this was to avoid publicizing Bryan’s alcoholism. Putting it all together makes me wonder if James was hinting that Bryan’s drinking had gotten out of control at the end.

Whether or not it was alcoholism or something else that led others to challenge Bryan’s sanity, perhaps it’s worth considering how hard his last few years would have been on him. While serving as judge, he had endured a nasty dispute with an attorney that continued for several years. His widowed sister Ann—with whom it seems he had been quite close—had died in 1846. His term as mayor was largely ineffectual due to squabbles with the city council. And possibly worst of all, 1848-51 was a period marked by widespread destitution, illness and death, anti-Catholic sentiment, and the great fire of 1849—all of which must have weighed heavy on a man who spent so much time and resources assisting the poor.

It’s plausible he sought solace in alcohol to cope with the immense pressures and personal grief he experienced. But as of now, I’m just not sure. Perhaps with more research, I will be able to answer some of these questions.

A highly contentious will

Moved by the struggles of immigrants arriving in St. Louis, Bryan Mullanphy was inspired to leave a significant part of his estate to support those seeking a new start in the West. In August 1849, Bryan went to the office of attorney Felix Coste and prepared his will. In his will (upon which, after his death, several men who knew him well attested to his sound mind), he allocated one-third of his vast estate—comprising real, personal, and mixed assets—to the City of St. Louis (the rest would be divided among his sisters).

This portion of his estate destined for the city, valued between $200,000 and $250,000—a vast sum at the time—underscored Bryan's commitment to immigrant welfare. It also led to a prolonged legal dispute initiated by his sisters and their husbands.

Oddly, sparking another mystery, at some point shortly after drafting his initial will, Bryan made an addendum. While at a saloon with friends, he decided to bequeath $1000 to a carpenter named William Dreyer, using a page torn from a book and getting his buddies at the bar, including the owner, to witness this addendum. I haven’t figured out who this Dreyer was to Bryan or why he earned this special bequest, as there was no other individual named in the will.

Shortly after drafting his will, Bryan gave the document to Col. D. H. Armstrong, the St. Louis Comptroller, who understood its importance and ensured its safekeeping with the City Registrar. This was likely a step he took after the controversy over his father’s will, which had gone missing after John Mullanphy died.

The legal battle over Bryan’s will, which extended to the Missouri Supreme Court over the city's capacity to inherit land among other concerns, concluded in 1861 after the family dropped their suits, and the will was deemed valid. However, the Civil War delayed the establishment of what would be termed the ‘Mullanphy Relief Fund’ until 1866.

The legacy of Bryan Mullanphy

Over more than a century, Bryan Mullanphy's legacy through his fund has made enduring contributions to St. Louis, extending his compassion to the needs of immigrants and the underprivileged well after his demise. His fund facilitated the creation of the Mullanphy Emigrant Home, providing a sanctuary for those journeying westward, irrespective of their origin. The Mullanphy Fund also led to the establishment of the Travelers Aid Society, an initiative that, over the years, grew from a St. Louis initiative to an international organization.

In addition to these lasting infrastructural contributions, Mullanphy's name has been honored in various community assets, including an apartment building, a school, a bank, and a park, weaving his legacy into the fabric of the city's everyday life. (As far as I can tell, Mullanphy Street was named after his father.) Due to his role in establishing the St. Vincent de Paul Society—an organization that helps people throughout the country, Bryan’s likeness is even immortalized in the mosaics of the Cathedral Basilica.

Bryan’s passing in 1851 was marked by accolades in the Republic newspaper in Washington DC, which celebrated him as “a man of splendid education, of fine genius, and a most excellent heart,” who was “charitable, without making an ostentatious show of it,” devoting much of his time to alleviating the suffering of the poor.

In today's climate, filled with anti-immigrant sentiment and social divisiveness, Bryan Mullanphy's example stands out as a beacon of tolerance, empathy, and action. His dedication to aiding immigrants and promoting a society that values and supports its most vulnerable members offers a compelling lesson for us all. And his life and contributions remind us of the impact that an individual’s commitment to justice and compassion can have on our community.

Thanks to Andrea Knobeloch, Adam MacPharlain, Amanda Bailey, Chris Naffziger, and Nathan Jackson for their professional assistance with different aspects of Bryan Mullanphy’s life, and to Dennis Northcott and Jaime Bourassa at the Missouri Historical Society for their assistance with the archival research and scans.

And thanks to Danny Wicentowski of St. Louis Public Radio for inviting me to discuss Bryan Mullanphy live on the air.

If you enjoyed this piece and would like to help me continue my investigations into Bryan Mullanphy and life in St. Louis in the 1840s, consider upgrading to a paid subscription to Unseen St. Louis. Your support helps make this kind of research possible.

Also, as this is an ongoing research project, if you have any additions, corrections, or suggestions on sources, books, or archives, I’d love to hear from you. You can leave a comment on this post or contact me directly at jackie @ jackiedana.com.

Sources

W. V. N. (William Van Ness) Bay, Reminiscences of the bench and bar of Missouri [electronic resource]: with an appendix containing biographical sketches of ... the judges and lawyers who have passed away: together with many interesting and valuable letters never before published of Washington, Jefferson, Burr, Granger, Clinton, and others, St. Louis: F. H. Thomas and Company, 1878.

Sandra M. Brunsmann. Early Irish Settlers in St. Louis, Missouri and Dogtown Neighborhood 1798-2000. St. Louis, 2000.

Alice Lida Cochran, The Saga of an Irish Immigrant Family: The Descendants of John Mullanphy. Dissertation, St. Louis University, June 1958. New York: Arno Press, Ltd., 1976.

John Fletcher Darby, Personal recollections of many prominent people whom I have known, and of events--especially of those relating to the history of St. Louis--during the first half of the present century, St. Louis, G. I. Jones and Company, 1880.

Lucy A Delaney, From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or Struggles for Freedom. St. Louis, MO: Publishing House of J. T. Smith, No. II, Bridge Entrance, [189-?].

Peter Downs, St. Louis Civil War Sites and the Fight for Freedom. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2022.

Edward Edwards, History of the Volunteer Fire Department of St. Louis. St. Louis: The Veteran Volunteer Fireman’s Historical Society, 1906.

Encyclopedia of the History of Missouri, Vol. 5, 1901.

William Barnaby Faherty, The St. Louis Irish: An Unmatched Celtic Comunity. St. Louis: The Missouri Historical Press, 2001.

Harriet C. Frazier, Slavery and Crime in Missouri, 1773-1865. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2001.

Fire Department History, City of St. Louis MO website

Harriet Lane Cates Hardaway, Descendants of John Mullanphy, St. Louis Philanthropist, 1940.

Frederick A. Hodes, Rising on the River: St. Louis 1822 to 1850 Explosive Growth from Town to City. Tooele, Utah: The Patrice Press, 2009.

David A. Lossos, Irish St. Louis. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.

Kerby Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Patrick Murphy, The Irish in St. Louis, St. Louis: Reedy Press, 2022.

Michael C. O’Laughlin. The Missouri Irish: The Original History of the Irish in Missouri. Kansas City, MO: Irish Genealogical Foundation, 1984, 2007.

Tim O’Neil, Look Back 250 • Cholera epidemic, firestorm afflict St. Louis in 1849, St Louis Post-Dispatch, March 10, 2014.

Papers of the Mullanphy, Chambers, Lamotte, O’Fallon families, Missouri Historical Society Collections.

George Potter. To the Golden Door: The Story of the Irish in Ireland and America. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1960.

The Radical (Bowling Green, MO), January 20, 1844.

Charles Van Ravenswaay, St. Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People 1764-1865. 1991.

The Republic (Washington DC) June 25, 1851.

St. Louis Integrated Database of Enslavement, Washington University.

St. Louis Firemen's Fund, History of the St. Louis Fire Department, With a Review of Great Fires and Sidelights Upon the Methods of Fire-fighting from Ancient to Modern Times, from which the Lesson of the Vast Importance of Having Efficient Firemen May be Drawn, 1914.

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 20 April 1890.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, various dates.

St. Louis Times, Sept. 29, 1878.

Anne Twitty, Before Dred Scott: Slavery and Legal Culture in the American Confluence, 1789-1857. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Walter Barlow Stevens, St. Louis: The Fourth City, 1764-1911 Volume 2, Loschberg, Germany: Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck, 2020.

Andrew Theising, ed. In the Walnut Grove: A Consideration of the People Enslaved In and Around Florissant, Missouri. Florissant, MO: Florissant Valley Historical Society, 2020.

Lea VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Lea VanderVelde, Redemption Songs: Suing for Freedom before Dred Scott. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Andrew Wanko, Great River City: New Faces on the Levee, Missouri Historical Society, August 7, 2020.

The WashU and Slavery Project

Some accounts suggest that John Mullanphy disinherited his son, and then Bryan’s sisters restored his inheritance, but upon my own review of the will, it appears he simply reduced the amount Bryan would inherit, which was still a sizable amount. The family appears to have redivided the estate in some way after probate, as this was a concern during Bryan’s probate later. I’m still trying to track this down.

The accounts date this story to 1850, but the Bates Theater apparently didn’t open until 1851.

From late 1841 on, Bryan had an ongoing dispute with one of the main freedom suit attorneys, Ferdinand Risque, and that may have led to Bryan’s resignation. I will be detailing this dispute in my March 21st talk and a future article here.

Thank you

Great work! Thanks for adding an interesting chapter to the city's history.