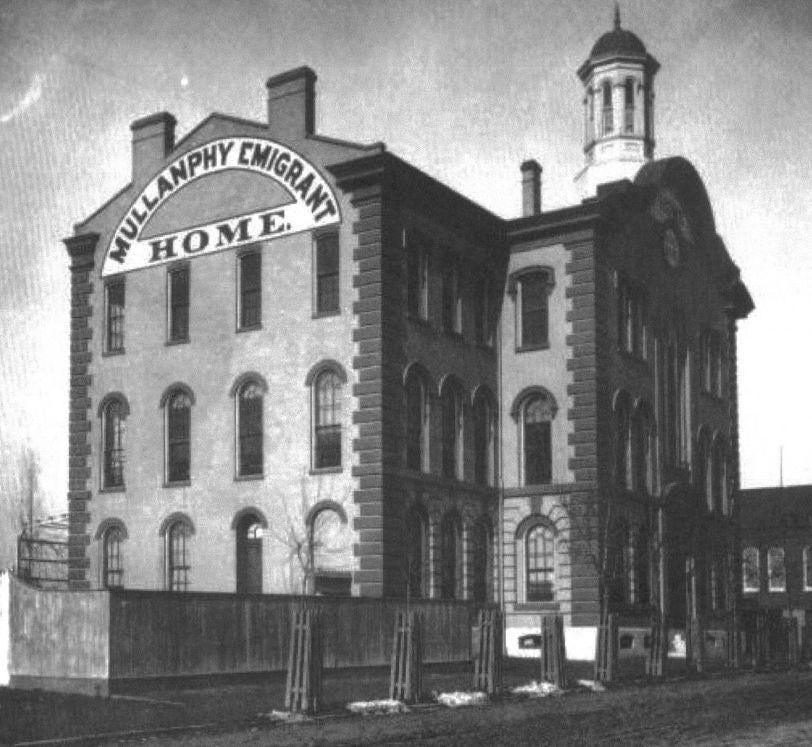

The Mullanphy Emigrant Home at 1609 N. 14th Street in north St. Louis burned down Thursday night, September 14th.

As I remark in many of my pieces, it wasn’t just an old building. Once upon a time, it symbolized hope, compassion, and the enduring spirit of St. Louis. Initially, it provided solace and a fresh start to countless individuals. It then became a school and later a factory, before eventually falling into disuse. And tragically, like so many of our city’s older historical structures, it fell victim to the twin ravages of time and neglect.

Over and over again, we hear this song played out, as structures with such deep roots in our shared history fall victim to mysterious fires. And again, the familiar refrain: if only more had been done.

In this retelling of the Mullanphy family and the 156-year-old building that met its demise on September 14th, I hope to share my appreciation for the city’s architectural heritage as I mourn the loss of yet another piece of our city’s history.

Who were the Mullanphys?

In order to tell the story of the Mullanphy Emigrant Home, we should first (briefly) recount the story of the Mullanphy family.

In 1792, Irishman John Mullanphy came to the United States. After meeting fur trader Charles Gratiot, Mullanphy moved to St. Louis in 1804, at a time when fewer than 1,000 people lived in the city. He made his fortune trading cotton, turning that money into real estate, becoming St. Louis’s first millionaire.

With some of his wealth, he pieced together a large plot of land in what is today Carr Square, just north of downtown, obtaining much of it through foreclosures and back taxes. Starting a trend of forward-thinking philanthropy in the family, he also built hospitals and orphanages starting in 1828 with the stipulation that they treat “all such indigent sick free persons without regard to color, country or religion.”

In the 19th century, John Mullanphy’s children did what they could to help the less fortunate in the new city, including their destitute fellow Irishmen and women who fled to the US during An Gorta Mor, the Great Hunger.

Out of the family, the one who is best well-known for his generosity and kindness was Mullanphy’s son Bryan, who served as mayor of St. Louis in 1847-48. Bryan Mullanphy is remembered as the only one in St. Louis willing to protect the printing press of abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy, and during his life, he gave away a great deal of his inheritance to assist the poor.

The St. Louis Bar passed a resolution upon his death at the age of 42, stating, 'All his oddities are but as dust in the balance when weighed against the uprightness of his life and the succession of his charities.”

Early days of the Mullanphy Emigrant Home

The Mullanphy Emigrant Home was designed in 1867 by architects George Barnett and Albert Piquenard. It initially served as a haven for European immigrants on their journey westward. George Barnett was among the first professional architects in St. Louis, while Albert Piquenard made a name for himself designing capitol buildings in Iowa and Illinois.

Back in 1867, it cost $30,000 to construct this 22,950-square-foot building, much of which was generously contributed by the estate of Bryan Mullanphy in what is known as the Mullanphy Emigrant Relief Fund (which still exists today!). Within six months, the Mullanphy Emigrant Home welcomed nearly a thousand travelers who were given a place to sleep and offered medical care, clothes, and even job assistance when needed.

But as the times changed, so did the purpose of the Mullanphy Home. By 1877, the wave of immigrants had slowed, and the building transformed into a school. Later on, it became the headquarters for the Absorene Manufacturing Company, known for its wallpaper cleaner.

Troubled period

In 2006, the vacant Mullanphy Emigrant Home faced significant storm damage, particularly to the south wall. Recognizing the historical significance of the building, the Old North St. Louis Restoration Group intervened. They utilized funds from various fundraisers and volunteer labor from E.M. Harris Construction Company and the Masonry Contractors Association to stabilize and restore parts of the structure.

In 2007, The Riverfront Times humorously acknowledged the efforts to preserve the Mullanphy Emigrant Home by designating it the "Best Lost Cause" of the year.

Michael Allen, an architectural historian and Director of the Preservation Research Office, commented in 2010 on the building's preservation, noting,

“The fact that this city still has the Mullanphy Emigrant Home is testament to the amazing mobilization of dedicated Old North St. Louis residents, preservationists and civic leaders across the city.”

While the Old North Restoration Group took care of the Mullanphy property for some time, the board eventually decided to sell the building. They hoped to find an entity capable of undertaking the renovation and reintegrating the structure into the community. Dr. Wahied Gendi of W&W Real Estate acquired the property in October 2018 for $130,000, with plans to transform it into a community center or hotel, estimating renovation costs at around $4 million.

Speaking to the Post-Dispatch after the fire, Andrew Weil, president of the Landmarks Association of St. Louis, acknowledged that Gendi “had these grand plans.”

Indeed, when he purchased the property, Gendi told St. Louis Style,

“I will do everything I can to preserve the history of this iconic building so that we can bring something valuable to this community. Whether it serves as a health facility or as residential housing, I will work hard to restore it back to its original glory in a way that best serves the residents of this area.”

Unfortunately, grand plans aren’t enough to save historic buildings if no action follows, and it’s unclear if Gendi ever did anything from 2018-2023 to shore up the building, even prior to storms a couple of years ago that caused further damage.

Fire destroys the Mullanphy Emigrant Home

And that brings us to the fire on the evening of September 14th that destroyed the building.

“It’s a real tragedy,” Weil said. “It’s an incredibly significant building — or was.”

The timing of recent events calls Gendi’s ‘grand plans’ into question. The Post-Dispatch reported that Gendi said an engineering firm determined that the structure was too dangerous to restore. Furthermore, he claimed he couldn’t obtain a loan to stabilize the building after recent storms.

However, the Post-Dispatch reported that Gendi never applied for building permits — but did apply for a demolition permit in May. The Cultural Resources Office had referred the application to the Preservation Board because the structure is in a National Register of Historic Places district, and the Board intended to evaluate the permit request later this month.

Yet, just before that hearing, the building burned to the ground. Gendi told the Post-Dispatch after the fire, “It’s very surprising what happened.”

After 156 years, it seems rather convenient that the building burned down just before the demolition permit was to be considered. But who am I to say?

When I visited the site on Friday, Sept. 15th, I spoke to a woman with the wrecking company, who said demolition would begin on Saturday. That means that by the time you read this, nothing may be left of this noble building that once offered hope and compassion to poor immigrants who found their way to St. Louis.

What will happen now? From what the wrecking company representative said, the owner plans to salvage what he can from the property to use in a new building, perhaps at the same site. It’s not hard to imagine a fast-food restaurant or car wash taking over the space. After all, as Chris Naffziger noted in the Riverfront Times back in 2014, it’s a “strategic and desirable site mere blocks from the new Stan Musial Veterans' Bridge entrance into downtown along Tucker Boulevard.”

Let’s hope Dr. Gendi — an immigrant himself — does better by Bryan Mullanphy’s legacy than that.

Thanks as always for reading. If you’re interested in historic architecture and preservation, you won’t want to miss Michael Allen and Emery Cox from the National Building Arts Center speak about all these things as part of our Unseen STL History Talks series on Sept. 21st.

Your support means a lot to me. If you have a moment, please share this article with others so they too can learn about the Mullanphys and this great loss to the city.

Sources

Michael R. Allen, Mullanphy Emigrant Home, Four Years Later, Preservation Research Office, April 9, 2010.

Jackie Dana, “Irish kings, gangs, and witches,” Unseen St. Louis, March 17, 2022

Walter Hamilton, New Hope for Mullanphy Emigrant Home, NextSTL, January 8, 2019

Chris Naffziger, “Mullanphy Emigrant Home: North St. Louis Landmark Slowly Returning to Glory,” Riverfront Times, March 19, 2014.

Chris Naffziger, Mullanphy Emigrant Home In Serious Trouble, St. Louis Patina, November 6, 2021.

Bryan Mullanphy, St. Louis Mayors, St. Louis Public Libraries.

Bryan Mullanphy, Wikipedia.

Mullanphy Emigrant Home to Undergo Major Renovation, St. Louis Style, May 20, 2019.

Mullanphy Emigrant Home, Missouri Preservation, November 11, 2006.

Mullanphy Emigrant Home and More Mullanphy, Built St. Louis.

Mullanphy Emigrant Home, Mound City on the Mississippi.

Photos: A look back at the former Mullanphy Emigrant Home building over 150 years, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 15, 2023.

Mullanphy Emigrant Home, built in 1867 to welcome immigrants to St. Louis, burns to ground, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 15, 2023.

I'm a descendant of Bryan Mullanphy. I had a good conversation with the owner about making a memorial there. Tried to save what stone work I could. But when I mentioned the men hauling pallets of bricks away Dr. Gendi told he can't do anything to secure the site and then stopped contacting me.

Thank you, I had been loosely following the buildings story and had not heard it had burned. Sorry to hear this.