2334 Olive: A Century of Progressive Politics

Surprising history of a site in St. Louis that may have escaped your notice until now

Welcome to Unseen St. Louis. This time around, I’m going to explore the history of a seemingly random building that turned out to have several quite surprising stories behind it. I hope you enjoy the ride!

At the corner of Olive and Jefferson in Downtown West St. Louis stands a building from 1968—a relatively recent addition to the city’s landscape. While this modern structure has its own unique story, the site is steeped in an even deeper history. This unassuming corner has been home to key moments in civil rights and political activism, witnessing the efforts of individuals and groups who fought for social change. The history embedded in this site serves as a reminder of St. Louis’ deep connections to these movements and the individuals who fought to make the city a better place to live.

The site also allows us to step into the future as it will serve as the campaign headquarters for another progressive leader, Cara Spencer, who hopes to continue the legacy of social change and reform in St. Louis.

Join me as I unlock the secrets of what is now 2334 Olive St.

The Olive and Locust Historic District

The area between Jefferson and 21st Streets, bordered to the north and south by Olive and St. Charles Streets, was once part of what is known today as the Olive and Locust Historic Business District, a neighborhood originally part of the historic Mill Creek Valley community .

Among the neighborhood’s key commercial and industrial establishments in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were the Columbia Incandescent Lamp Company, Lambert Pharmacal Company, and Standard Oil Company. The area also housed a perfume manufacturer and a printing company, with the Hurck Motor and Cycle Company at 2113 Olive eventually transforming into a Harley-Davidson dealership by 1951. At 23rd and Olive, you could find Thomas Sheehan's plumbing company, which thrived from 1922 into the 1950s in a building that still bears his name today. Nearby, you could find the Erker Brothers’ optical lab, the first of its kind west of the Mississippi. And at 23rd and Locust you would encounter the Otis Elevator Company offices.

But the area also hosted a number of social services that provided care for local residents. A resident might have visited the People’s Hospital, built in 1909 on Locust, which served as a vital community center, hosting the St. Louis American Red Cross and Missouri Tuberculosis Council. The Sisters of Mercy also contributed to the neighborhood's social services, founding an infirmary and home for girls at 2210 Locust.

This district, known for its manufacturing and retail businesses, was also home to Automotive Row. This may have been because Olive and Locust were paved with granite before 1895, aiding transportation and fostering the area’s development into a retail hub. There were also many residents in the area, as many of the buildings housed businesses on the first floor and apartments above.

The Midway Building

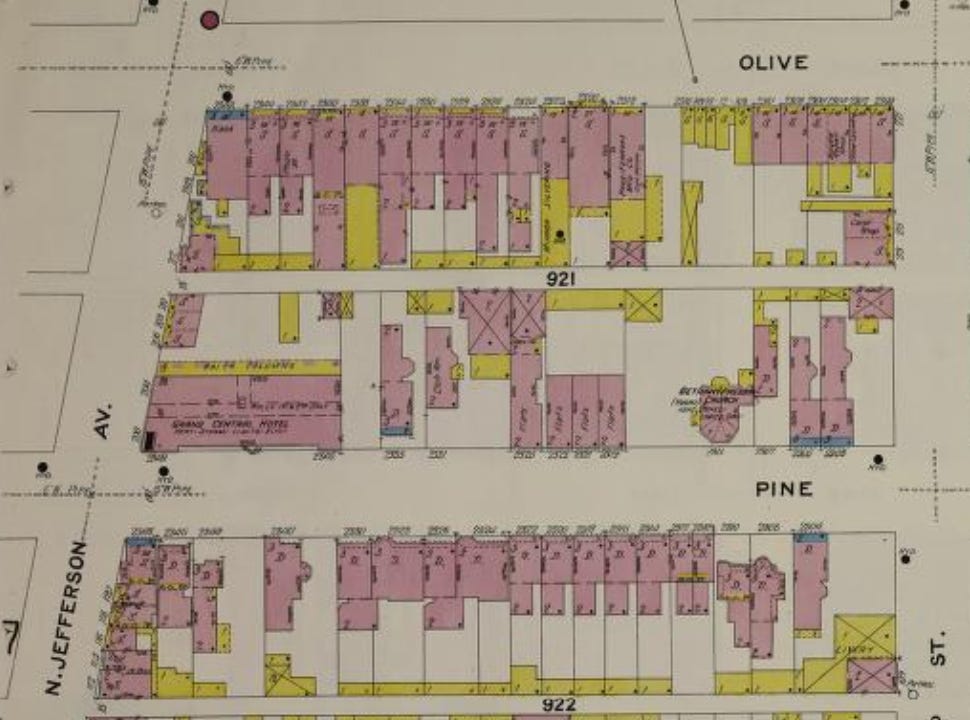

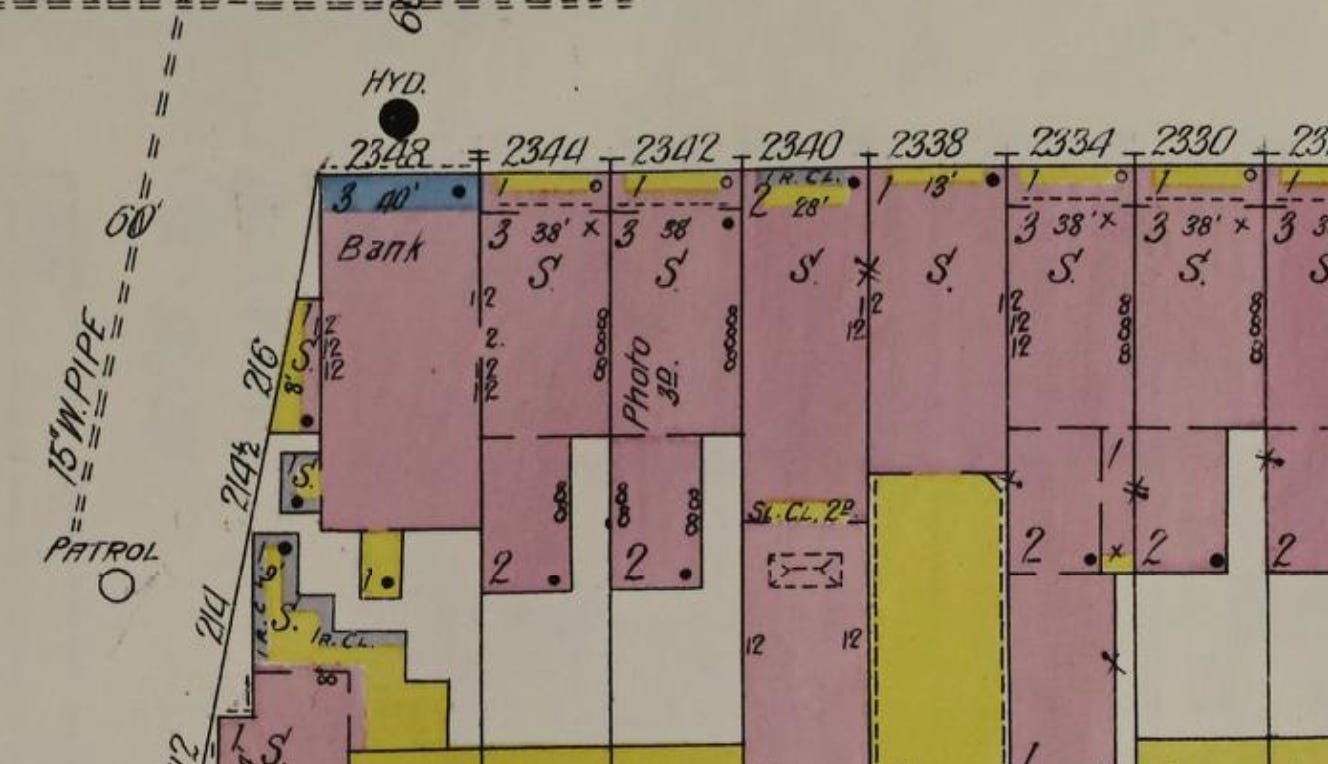

But back to our location. As anyone researching old buildings in the city will tell you, many addresses have changed over the years, and this block of Olive was no exception. Based on the 1909 Sanborn fire insurance map, the building at the southeast corner of Olive and Jefferson—today 2334 Olive—was once 2348 Olive.

You can view the Sanborn map of this area below:

Below is an enlarged detail of the above map, allowing you to better make out the building in question in the top left corner:

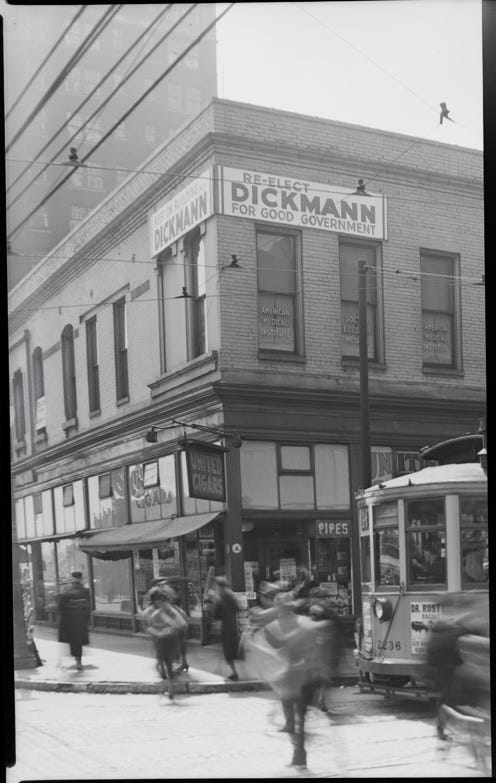

According to a different map from 1905, the building at this address was the location of the Phoenix Building & Security Co., but it looks like that company relocated to the Railway Exchange Building after 1913. After that, records indicate the building became known as the Midway Building. By the 1920s, the bottom level of the building, initially marked on the Sanborn map as a bank, had become a cigar shop and billiards hall, with residential apartments upstairs, which, as noted above, was a common feature of this neighborhood.

You can see a bit of the Midway Building below, which was still a cigar shop in 1937 when this photo was taken.

It’s worth noting the “Re-elect Dickmann” sign, which is an interesting tidbit. Bernard Dickmann had been elected mayor in 1933 as the first Democratic mayor in 24 years, an office he would hold until 1941. (As an aside, in the 1930s, Dickmann, along with Luther Ely Smith, successfully, albeit somewhat fraudulently, campaigned to demolish the riverfront neighborhood for what would, two decades later, become the grounds for the Gateway Arch.)

Progressive Politics in the 1920s

A few tenants of the Midway Building are particularly interesting.

The Progressive Party made their St. Louis headquarters in the building in 1924. The party was led by Robert "Fighting Bob" La Follette, a prominent reformer from Wisconsin.

La Follette, known for his fierce resistance to the corrupt influence of railroads, utilities, and large corporations, sought to put the power of government back into the hands of the people. His vision, known as the "Wisconsin Idea," encouraged collaboration between public leaders and academic experts, recognizing that education should extend beyond the classroom and that research could address real-world issues. As Governor of Wisconsin, La Follette introduced significant reforms, including the regulation of railroads, workers’ compensation laws, a state income tax, and the establishment of the direct primary. His reforms positioned Wisconsin as a model for progressive governance.

La Follette’s influence extended to the national stage when he became a U.S. Senator in 1906 and later a leading figure in the Progressive Republican movement. He opposed the conservative policies of President Taft and even sought the presidency himself in 1924 under the Progressive Party's banner. His platform was notable for its opposition to the Ku Klux Klan and its advocacy for public ownership of utilities, labor rights, and farm relief. Though La Follette finished third in the election, his progressive ideals gained substantial support, with over five million votes. The principles he championed continued to influence American politics, helping to shape key components of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and later progressive initiatives under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson.

And it was at the Midway Building at Olive and Jefferson that Progressive Party workers campaigned for La Follette and these political reforms.

From Progressive Politics to Civil Rights

The Midway Building had several apartments on the upper floors. One resident was attorney Homer G. Phillips, who listed 2348 Olive as his address in 1926.

Phillips was a prominent Black attorney, community leader, and activist in St. Louis. Born in 1880 and raised in Sedalia by his aunt, he earned his law degree from Howard University in 1903. By 1911, he had moved to St. Louis and established a successful legal practice.

Phillips quickly became a key figure in civil rights and local politics, founding the Citizens' Liberty League to fight for Black rights after St. Louis residents voted in 1916 to enforce segregation in housing. He led the opposition to the ordinance, which barred Black residents from moving into neighborhoods where 75% or more of the population was white. Although his initial injunction to prevent the special election on the measure was denied, Phillips and the local NAACP secured a temporary injunction that delayed the ordinance's enforcement. This legal maneuver, pending the Supreme Court's decision in Buchanan v. Warley, ultimately led to the ordinance being declared illegal.

A member of the Republican Party, as was common for many Black Americans before the New Deal, Phillips unsuccessfully challenged incumbent Congressman Leonidas C. Dyer, the nephew of the judge who granted the injunction, in the 1926 Republican primary.* (This was when he listed his address as 2348 Olive St.)

Phillips also played a critical role in defending Black soldiers who had been court-martialed after the 1917 East St. Louis massacre and represented African Americans in several criminal cases related to the riots. In the early 1920s, he helped found the St. Louis Negro Bar Association, and in 1927, he was elected president of the National Bar Association, a national organization of Black attorneys.

Today, Phillips is best known for advocating for a new hospital for St. Louis' Black community, as the existing City Hospital No. 2 was inadequate. Tragically, he never saw the hospital completed. On June 18, 1931, at the age of 51, Phillips was fatally shot while waiting for a streetcar on Delmar Boulevard. The motive was believed to be related to a fee dispute, but despite two trials, his alleged assailants were acquitted. In recognition of his contributions, the St. Louis Board of Aldermen named the new hospital in his honor.

* A note about Dyer: in 1918 he proposed an anti-lynching bill in Congress. Although it passed in the House of Representatives, it failed in the Senate due to a filibuster in the Senate by southern Democrats. You can read the text of the bill on the NAACP website.

A Modern Structure

In 1968, a new chapter began for the Communications Workers of America (CWA) with the completion of a modern office building on the site of the old cigar shop and neighboring structures. This building, designed for both the Regional and Area Offices of the CWA, was a striking departure from the past, embodying the principles of modern architecture and marking a significant moment for the union.

To appreciate the significance of this new office building, it's essential to delve into the history of the CWA and its strong ties to St. Louis. Founded in 1947, the CWA became a vital advocate for telecommunications workers in an industry dominated by major employers like AT&T and Southwestern Bell. AT&T, initially founded in St. Louis in 1878 as the American District Telegraph Company, grew into a telecommunications giant, while Southwestern Bell began as the Missouri and Kansas Telephone Company and later became a key subsidiary of AT&T. With these companies at the heart of the local economy, St. Louis emerged as a hub for communications, making the CWA a crucial force in securing the rights of workers across the region.

Nationally, the CWA rose to prominence through decades of struggle against the monopolistic Bell System, with numerous strikes and organizing efforts that culminated in its establishment as the largest communications and media labor union in the U.S. By 1949, the CWA had affiliated with the CIO, cementing its influence with over 700,000 members today. Locally, the union’s efforts improved working conditions and wages for thousands of employees, extending into other sectors like media and public radio.

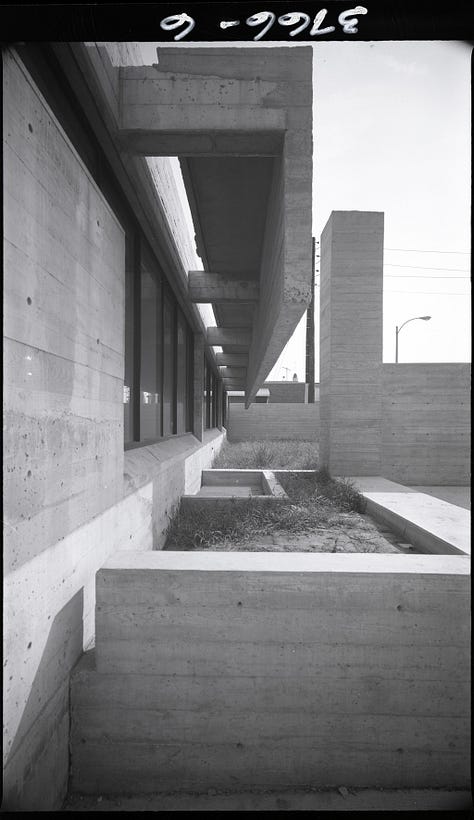

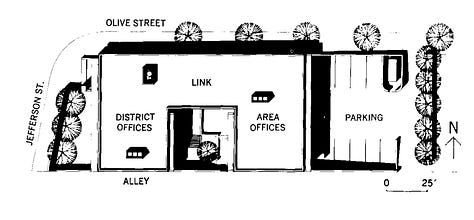

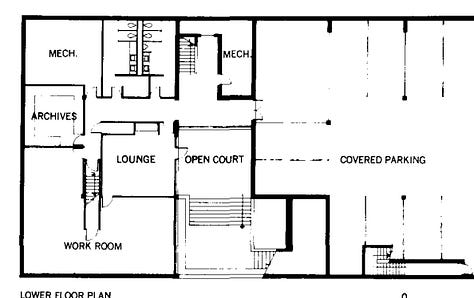

The dramatic new structure that the CWA commissioned in 1968, designed by Anselevicius/Montgomery/Rupe Architects, brought a modern aesthetic to the neighborhood. The building’s design offered a fresh take on the office environment, featuring a private courtyard, covered parking, and unusual elevations.

Architect George Anselevicius explained in 1970: "Our main intent was to deinstitutionalize an office building, to make it almost a house." The 14,000-square-foot structure, built for $450,000, provided separate wings for the regional and local offices while sharing facilities like the reception area and lounge.

Privacy and comfort were central to the design. A narrow court on the west buffered the offices from the street, while a landscaped parking area on the east provided breathing space. The central courtyard offered a private, calming environment for all the offices. Over time, the building evolved, with "alumicore" cladding added in 1986 to improve heating and cooling efficiency, covering the original concrete exterior made from Meramec bottom gravel. In 2018, Dan Pollmann purchased the building, and his wife redesigned the interior using custom furniture from Martin Goebel.

A new progressive leader moves in

In Fall 2024, the building at 2334 Olive will become the new HQ for the Cara Spencer for Mayor campaign.

Much like the La Follette Party and Homer G. Phillips before her, Cara Spencer is dedicated to making St. Louis a better place for everyone to live, regardless of race or social class. Her platform focuses on bringing transparency to city politics, helping residents tackle everyday challenges, protecting the city's historic landmarks and architectural treasures, and breaking down the barriers that divide us—all while working to restore pride in our beautiful city. Having served on the St. Louis Board of Aldermen since 2015, Cara brings a deep understanding of the city’s challenges and opportunities to her run for Mayor.

To learn more about her vision for St. Louis, visit her website—or soon, stop by the historic site that will become her campaign headquarters at 2334 Olive. And while you're there, take a moment to appreciate the building's modern architecture and reflect on the rich history that surrounds you—history that helped shape the city’s future, just as Cara aims to do.

(Disclaimer: although Cara suggested this topic, she did not compensate me for this article or tell me what to write. It just felt like a fun challenge and a way to help her campaign.)

If you enjoyed this piece of St. Louis history, I’d love it if you’d show your support by subscribing to Unseen St. Louis and sharing this article with your friends!

Sources

Paul Y Anderson, “La Follette’s Announcement of Presidential Candidacy,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 06 July 1924.

Architectural Forum, US Modernist July 8, 1970 pg 70-73.

AT&T, Wikipedia

CWA History: A Brief Review 1910-2024, Communications Workers of America.

Communication Workers of America, Wikipedia

Jackie Dana, You get a hospital, and you get a hospital…, Unseen St. Louis, July 1, 2022.

Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, NAACP.

“Fifty Year Backward Glance in St. Louis,” The St. Louis American (1949-2010); St. Louis, Missouri. 27 Dec 1973.

Guide to the Communications Workers of America Records, NYU Libraries.

Tim O'Neil, A look back - The day Homer G. Phillips was gunned down in St. Louis. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 18, 2023.

Homer G. Phillips, Missouri Encyclopedia.

Homer G. Phillips, Wikipedia.

Dan Pollman, owner, 2334 Olive.

Progressivism and the Wisconsin Idea, Wisconsin Historical Society.

Robert La Follette, Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickenson State University

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Saint Louis, Sanborn Map Company, Vol. 2, 1909, image 9. Library of Congress.

Southwestern Bell, Wikipedia

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Mon, Jul 26, 1926.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Wed, Sep 10, 1924.

Washington University Magazine, Winter 1975.

I seriously have to think that Phillips was murdered because the local white establishment had gotten tired of an "uppity" Black man challenging them politically. The fee dispute was likely a dodge to deflect blame towards him.