You get a hospital, and you get a hospital...

The segregated nature of early St. Louis healthcare

Welcome to Unseen St. Louis, where I explore underappreciated aspects of St. Louis history.

Last week I was rather ill and ended up in the ER (not with COVID). I feel much better now, but as a consequence of the illness, I fell way behind on writing and researching for my next article for this newsletter as well as its sister publication Story Cauldron.

However, my experience inspired me to look back at the history of some of the noteworthy hospitals in St. Louis. I hope you find this as interesting as I did!

Hospitals, hospitals everywhere

When you’re in St. Louis, you really can’t throw a rock without hitting one of our local hospitals, which seem to be everywhere. There are the Mercys, the string of Catholic hospitals named after every conceivable saint (except one which isn’t Catholic), the giant Barnes-Jewish complex towering over Forest Park, and lots of smaller hospitals and clinics and outpatient facilities (not to mention the urgent cares on nearly every corner).

Growing up here, with my mom working as a nurse in one of them, I was always aware of the different hospitals, even though I never went to most of them. My mom talked about them a lot, and how patients came from one hospital or were transferred to another, how one hospital was overloaded, or whatever. So even though I knew little about them, I knew all the names.

So writing this was a strange bit of nostalgia, but it also highlighted how little I knew about any of the hospitals, including the one she worked at for most of my life.

And I discovered that in St. Louis through the 1950s, everyone had their own hospital. Depending on whether you were Catholic, Jewish, or Protestant; Black or white; rich or poor; or an adult or child, which hospital you would go to was largely pre-determined.

The good news is that today, you can go to any hospital you want and the choice is more based on location and the type of care you need rather than your personal identity. But it wasn’t always that way.

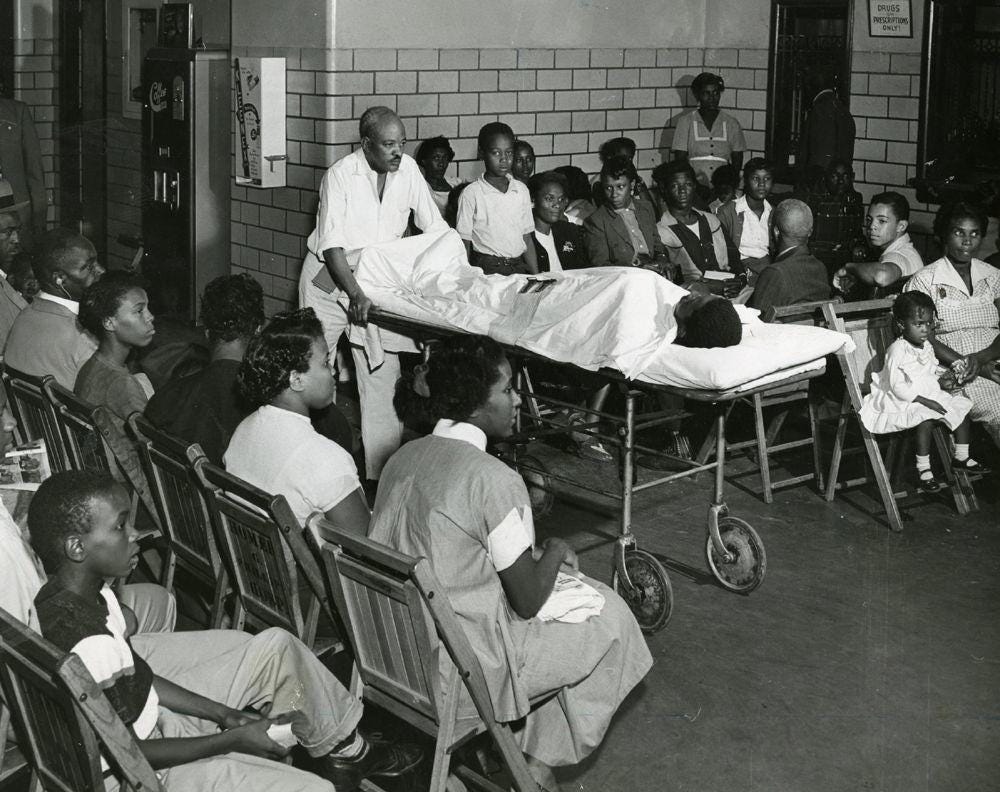

Homer G. Phillips Hospital

Homer G. Phillips Hospital was an important institution in St. Louis. For many years it served an important role in the city. Built in 1937 at 2425 Whittier St. in the vibrant Ville neighborhood, it was the main hospital serving the Black population in a segregated city. In time, it became nationally recognized for its research and healthcare and was one of the few places in the US providing education and training to Black doctors, nurses, and technicians.

The hospital was named for Homer Garland Phillips, a local lawyer, community leader, and civil rights activist. He also owned two Black St. Louis newspapers. In 1923 he successfully campaigned for a bond issue to build a new hospital. At the time the only hospital serving the Black community was the insufficient City Hospital No. 2 in the Mill Creek Valley neighborhood.

Phillips never got to see his hospital completed. He was shot on the morning of June 18, 1931, at the age of 51. He was on Delmar Blvd. waiting for a streetcar and reading a newspaper when two men assaulted him and then shot him. Police had two suspects, men who disputed the fee he charged for settling the estate of the late George Fitzhugh. In two different trials, the two men were acquitted.

When the new hospital was completed, the St. Louis Board of Aldermen decided to name the new Black hospital after Phillips.

In 1955 St. Louis Mayor Raymond Tucker decreed that Homer G. Phillips had to serve all St. Louis residents regardless of race, ending the hospital’s tradition as an exclusively black institution.

The hospital closed in August 1979. The nurses’ wing became low-income housing in the 1990s and in 2004, it became a senior housing center now named the Homer G. Phillips Dignity House.

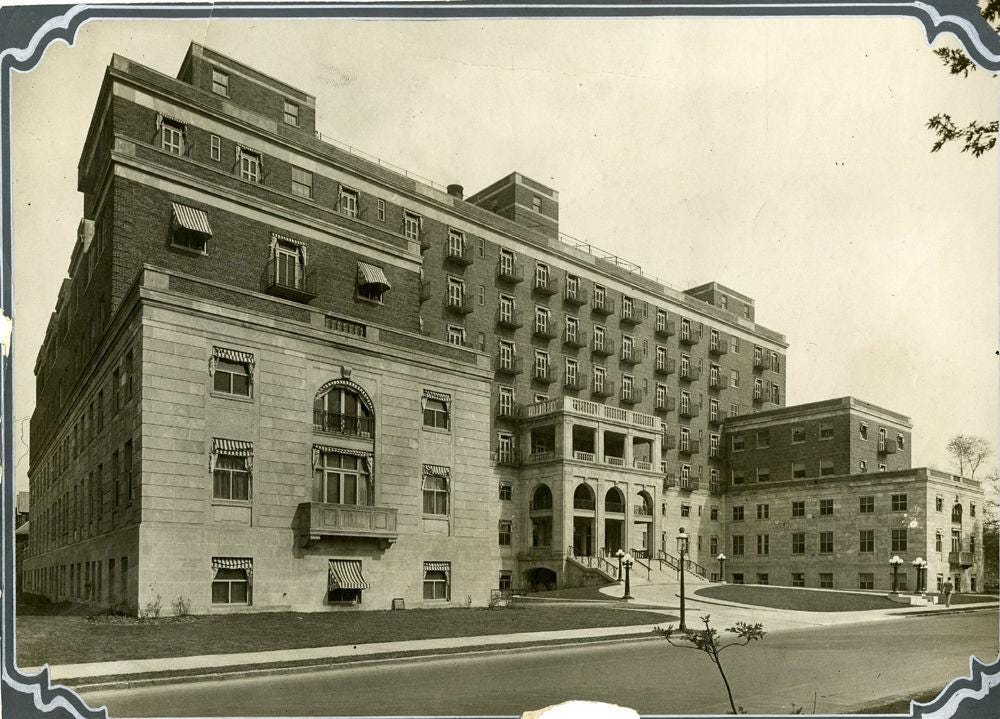

Jewish Hospital

Jewish Hospital is special to me. This is where I was born and where I would go for various medical issues as a kid. Although she was Catholic, my mom worked there for many years, including several years as the Emergency Room supervisor. When I was in grade school I had breakfast with my parents in the cafeteria (which had great food!) every day before school, and I would often use the bathroom and get snacks in the gift shop after school when my dad and I went there to pick her up after work. Even though I haven’t been inside the building in decades, I was still sad to see that it had been demolished.

Jewish Hospital started out in 1901 when the work began on the first hospital to serve the St. Louis Jewish community, located at 5415 Delmar Blvd. It was established to take care of the many Jewish refugees in the city, but from the start, it operated under the directive to care for people of “any creed or nationality.” The hospital proved popular, treating 2000 patients a year in 1915, and was expanded multiple times. Eventually, it became clear that a new hospital was needed. Just 26 years later, on May 16, 1927, a new and much larger Jewish Hospital was completed at the corner of Kingshighway and Forest Park.

After the first full year of operation, the new hospital had already treated over 5000 patients. In the 1950s it merged with the Jewish Sanatorium, the Miriam Rosa Bry Convalescent-Rehabilitation Hospital of St. Louis, and the Jewish Medical Social Service Bureau, and work began to expand the hospital further. The hospital became one of the original participating institutions in the new Washington University Medical School and Associated Hospitals (WUMSAH) program in 1962, and the next year it was one of the teaching hospitals affiliated with Washington University Medical School.

In 1992 Jewish Hospital signed an agreement to pool resources with Barnes Hospital next door, creating Barnes-Jewish, Incorporated (BJI), which then became BJC Health System the following year. In 1996 the two hospitals officially merged as Barnes-Jewish Hospital and it is nationally recognized as one of the best hospitals in the country.

Although Jewish Hospital continues to this day, the Jewish hospital building that formed part of the Wash U Medical Center was vacated in 2019 and demolished in March 2021.

Deaconess Hospital (Forest Park Hospital)

My dad and I spent many years community to school and work along what locals call Highway 40. In a prominent location across the highway from Forest Park was Deaconess Hospital, also referred to as Forest Park Hospital.

The first Deaconess Central Hospital was built at 2119 Eugenia St. 1889 by the Evangelical Deaconess Society of St. Louis (part of the religious organizations that would later become the United Church of Christ). By the time the hospital at 6150 Oakland Avenue opened in 1930, it was already on its third incarnation.

In 1997 the hospital was sold to Tenet Healthcare Corp. of Dallas with proceeds establishing the Deaconess Foundation, which provides grants to children's organizations. In succeeding years it was sold or acquired a few more times, and suffered financial difficulties until it was closed in 2011, and the St. Louis Zoo acquired the property for future expansion in 2012. The building was demolished in 2014.

Right now the site of the hospital is an empty field, and I wasn’t able to find any evidence of plans for its development since the St. Louis Zoo purchased the property.

St. Louis City Hospital No. 1 and No. 2

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, St. Louis had two city-run hospitals, and as was the case with so many of the local healthcare facilities, segregation was the norm, and one hospital treated white patients while the other treated Black patients.

City Hospital No. 1

In 1845 St. Louis was in the grip of one of several cholera epidemics that ultimately killed thousands. As a response, city officials passed an ordinance on July 10, 1845 to authorize the purchase of land and construction of a City Hospital. The first hospital building, located at today’s 14th St. and Lafayette Ave. This building was destroyed by fire in 1856, and the second building fell victim to the catastrophic 1896 tornado.

The third hospital, located at the same address, was completed in the early 1900s. As a St. Louis Star-Times reporter wrote in August 1937 (and as quoted in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch), the hospital served

"the indigent sick, the victims in summer and exposure cases in winter, victims of industrial accidents, fires, explosions, stabbings and all the other misfortunes incident to the swift pace of any metropolis.”

A large hospital complex that served the city for many years, City Hospital No. 1 was closed down in 1985. The complex was turned over to the St. Louis Land Reutilization Authority in 1992. Because it is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the complex was able to receive federal funds for a huge environmental cleanup and renovation. Renovated and new buildings on the site now feature condominiums, a climbing gym, an event space, a catering company, and A. T. Still University–Missouri School of Dentistry and Oral Health.

City Hospital No. 2

The second City Hospital was located at 2945 Lawton Avenue in Mill Creek Valley, a largely Black community just east of St. Louis University that would be razed in the 1950s.

In 1919, when the city established the public hospital, there was a huge need for healthcare for the city’s increasing numbers of Black residents. This was the period of the Great Migration when Blacks in the South moved to urban areas in the Midwest, and the only hospitals that would see Black patients were the private hospitals St. Mary’s Infirmary on Papin and 15th Street and Peoples Hospital on Locust. Neither would treat patients that could not pay for services upfront.

In an interview, former Mill Creek Valley resident Mary Covington explained the segregated nature of the city, saying, “We knew what hospitals to go to, and what streets we could not go pass [sic].”

However, unlike most hospitals (including City Hospital No. 1) that were built specifically for that purpose, the city decided to establish No. 2 in the former Barnes Medical College building.

Apparently the medical college had not been successful, and after it shut down the building spent some time as a hotel, then it was the Centenary Hospital for a while, before finally becoming City Hospital No. 2 in 1919. By then, it appears the facility wasn’t in the best condition, but at the time there was no one to champion a bond issue.

When it opened, City Hospital No. 2 and its 500 beds served this growing population. It also trained Black doctors.

Eventually, this hospital proved inadequate, leading to the construction of what would be called Homer G. Phillips, as noted above.

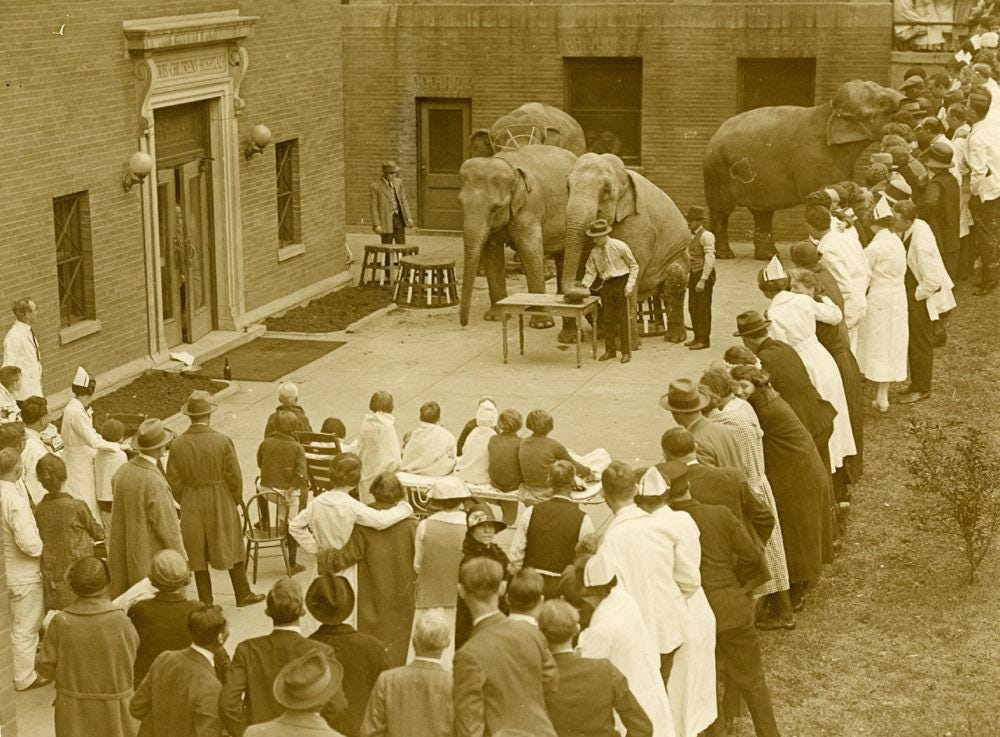

Shriner’s Children’s Hospital

The first Shriners’ Hospital building in St. Louis was completed in 1924 at Kingshighway and McKinley Ave., and then expanded in 1928. It was one of the first Shriners’ Hospitals in the US, built like the others at the time to address a terrible epidemic of polio in children. Over time, the hospital worked with children with orthopedic and mobility impairments.

As an innovator in the field, the St. Louis hospital hosted a successful operation to lengthen a child’s leg back in 1924, and in 1930 introduced an innovative technique to use traction to correct congenital dislocation of the hip. As noted in the photo above and at the top of the article, they were also known for bringing a bit of the Shriners’ Circus to the hospital to entertain the patients.

Shriners’ Children’s Hospital moved in 1963 to a new location on S. Lindbergh Blvd. in Frontenac, and in 2015 moved to Clayton Road, just two blocks away from its original location, which underwent renovation and opened as apartments in 2019.

Today the hospital cares for children with orthopedic needs, as well as other specialties including craniofacial conditions, spinal cord injuries, colorectal and gastrointestinal care, and sports medicine.

St. Louis County Lunatic Asylum/City Sanitarium/St. Louis State Hospital

Standing prominently on Arsenal Blvd. on the Hill, with its gleaming cast-iron dome designed by William Rumbold (who also designed the dome on the Old Courthouse in downtown St. Louis), it’s impossible to miss.

In 1846 the tract of land for the future hospital was set aside, and the grand public St. Louis County Lunatic Asylum opened a number of years later on April 23rd, 1869. Although located within the City of St. Louis today, it was opened and operated by St. Louis County (this was before the “Great Divorce” of 1875 when the City pulled itself out of St. Louis County.) After the separation, the hospital was renamed the "St. Louis Insane Asylum."

On opening day a number of patients (variously listed as 129 and 150) were admitted to the hospital, and the numbers grew steadily from there. In 1907, the hospital began work on a number of wings and annexes to accommodate the more than 2000 patients now needing its services.

In 1912, the "Million Dollar Annex" expanded the hospital considerably, and after a bond issue, the original hospital was fire-proofed, and the hospital added a large auditorium, cafeteria, and other buildings. More additions were made in the 1960s with the Kohler Building.

In 1948 the City of St. Louis sold the hospital to the State of Missouri for one dollar.

Eventually, instead of an “asylum” where people were essentially removed from society, the State Hospital became a highly-regarded institution to treat mental disorders. Some of the buildings were torn down in the 1990s, and the hospital moved into a new building at 5300 Arsenal in 1997 and was renamed to the St. Louis Psychiatric Rehabilitation Center. (For the curious, in 2019 the Post-Dispatch published a number of intriguing interior photos of the original building).

Today, the South Side YMCA occupies a building on the property.

I hope you enjoyed this look back at some historic hospitals in St. Louis. If you have memories of time in any of these hospitals or others in the area, I’d love to hear from you in the comments. I’d also be interested in ideas you may have for future articles. Be sure to leave a comment, and subscribe to get future articles from Unseen St. Louis.

Sources

Barnes-Jewish Hospital, History.

Tim Bryant, “Old Shriners Hospital in St. Louis to be rehabbed,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 30 January 2015.

“The Color Of Medicine: The Story Of Homer G. Phillips Hospital,” St. Louis City Talk, 20 May 2020.

Deaconess Hospital (St. Louis, Missouri), Wikipedia.

Shonda D. Gray, “City Hospital No. 2: Origins, Evolution, Regression, and Remembrance,” Decoding the City.

Valerie Schremp Hahn, “150 years: From Lunatic Asylum to St. Louis Psychiatric Rehabilitation Center”, Post-Dispatch, 23 April, 2019.

History of Shriners Children's St. Louis (Shriners Hospital).

Alex Ihnen, “Historic Shriners’ Hospital May Avoid Wrecking Ball,” NextSTL, January 2015.

Rachel Lippmann, “The 'Bittersweet Progress' Of The Demolition Of St. Louis' Old Jewish Hospital,” St. Louis Public Radio, 16 May 2013.

David A. Lossos, “Early St. Louis Hospitals, Homes, and Asylums,” 2011.

Chris Naffziger, “4 lost or forgotten St. Louis landmarks we should remember,” St. Louis Magazine, 2018.

Chris Naffziger, “Centers of community that were destroyed in the Mill Creek Valley” St. Louis Magazine, 26 September 2019.

Beth O’Malley, “Decades of service from St. Louis-area hospitals.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 4 September 2019.

Tim O’Neil, “A look back — The day Homer G. Phillips was gunned down in St. Louis,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 18 June 2022.

Steve Patterson, “Jewish Hospital Merged With Barnes Hospital in 1996, But An Older Jewish Hospital Building Remains Integral To Current Treatment,” Urban Review, 27 October 2021.

Adrienne Wartts, Homer G. Phillips (1937-1979) Black Past, 25 October 2008.

I worked at Forest Park Hospital from August 1999 until October 2005. What a great place to work! I was a surgical technician there and that was my first job. Everyone was great! The doctors, nurses, and even the secretaries! The operating room schedule was booming! We did everything from ENT, ortho, neuro, urology, and general surgery. On occasion, I would go to the surgery center to scrub eyes and hated it! But I learned so much and now I’m scrubbing eyes at my current job and it’s been a full circle moment for me! I learned so much now and I credit it to the nurses and techs and Forest Park Hospital

Very interesting article! I was born at Firmin Desloge Hospital in 1955. Like me, I'm happy it's still standing!