St. Louis Riverfront Clearances

The convergence of politics, real estate, and preservation efforts in the 1930s

In May 2024, I gave a presentation on the riverfront clearances as part of our monthly Unseen STL History talks. The following article is based on that research.

When someone thinks about St. Louis today, one of the first things that inevitably comes to mind is the Gateway Arch. As an iconic symbol for the city and the tallest monument in the US (and second in the world, with only the Eiffel Tower taller), it is undoubtedly a remarkable and significant part of St. Louis.

However, the Arch has only graced our city’s skyline for just shy of 60 years. Before then, an entire neighborhood existed along the riverfront, with some of the oldest structures in the city including commercial storefronts, warehouses, apartments, boarding houses, saloons, artist spaces, and industrial buildings.

Let’s consider what the riverfront was like before the Arch was built, the schemes city leaders engaged in to tear down the existing buildings, and the bits of history we lost along the way.

The Dream

The initial concept of transforming St. Louis’s riverfront was heavily influenced by the early 20th-century “City Beautiful” movement, which promoted monumental architecture to foster civic pride and social order.

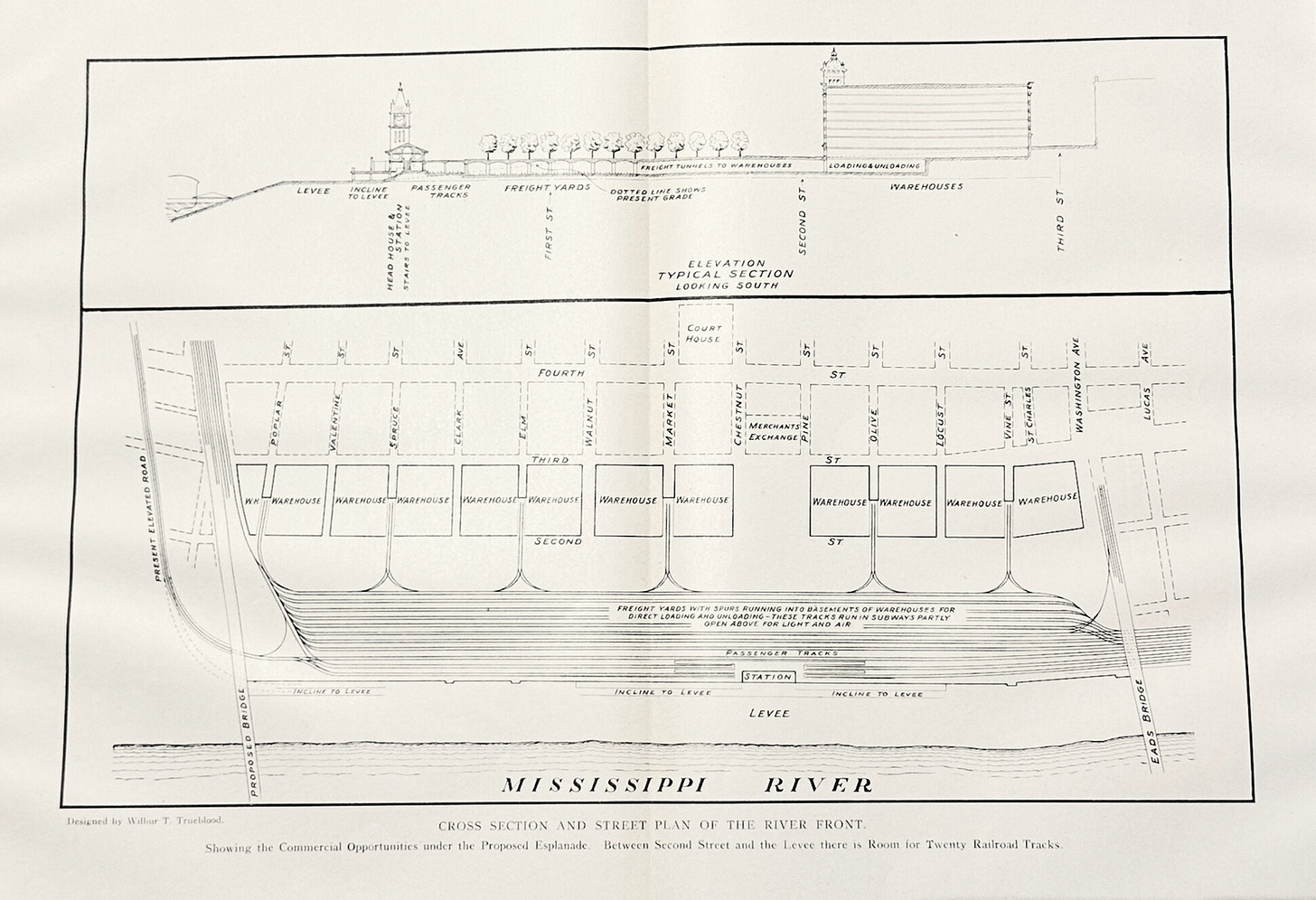

Inspired by this ideology, the Civic League of Saint Louis drafted a comprehensive city plan, “A City Plan for St. Louis 1907,” focusing on municipal buildings, parks, civic centers, street improvements, etc. Planners envisioned the riverfront as a scenic public space with classical structures and formal plazas, replacing industrial clutter.

In 1915, architect J. L. Wees proposed a riverfront plaza with a giant arch similar to the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, topped with a statue of St. Louis the crusader king. In 1916, St. Louis’s first full-time city planner, Harland Bartholomew, oversaw architect Hugh Ferriss’s design for a grand mall and memorial along the levee, aiming to beautify the area and stabilize property values. However, the $50 million cost proved too expensive, and the plan was eventually dropped.

The Men Behind the Project

Although the earliest plans for the riverfront didn't come to fruition, the idea of redesigning the area never completely faded. A couple of decades later, two men—Luther Ely Smith and Bernard Dickmann—joined forces to continue the efforts where the Civic League had left off.

Trained as an attorney, Luther Ely Smith quickly turned his focus to civic functions. In 1914, he was one of several committee members that put together the elaborate Pageant and Masque of St. Louis on Art Hill in Forest Park. This initiative would later evolve into the Muny, the oldest and largest outdoor musical theater in the United States. In 1916, Mayor Kiel appointed Smith to become chairman of the City Plan Commission, and Smith hired Bartholomew. After World War I, Smith was behind the building of structures like the Civil Courts Building and Kiel Auditorium. His involvement in urban planning and historical preservation extended beyond St. Louis—in the 1920s, he played a crucial role in establishing the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park in Indiana.

In the 1930s, St. Louis, like the rest of the nation, suffered during the Great Depression. Recognizing the need for civic pride during such challenging times, Smith resurrected the 1907 city plan for the riverfront. He framed it as an opportunity to build a monument to westward expansion, one that would celebrate the city’s history while also boosting the economy through job creation and increased tourism.

Smith would join forces with real estate developer and new mayor Bernard Dickmann. Dickmann had joined his father's real estate company in 1907, becoming president of the company in 1923. In 1931, he became president of the St. Louis Real Estate Exchange. Two years later, in April 1933, Dickmann was elected as the first Democratic mayor in 24 years, signaling a significant political shift in St. Louis. Dickmann seemed to recognize from the outset how important a successful, high-profile project would be for his political career and re-election.

The Scheme

By late 1933, Smith brought his plan to the city leadership, and in April 1934, the two men, along with other civic leaders and businessmen, formed the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association (JNEMA).

The objectives of the JNEMA were:

to revitalize the riverfront district by removing old buildings and railroad yard debris

to create employment opportunities during the Depression through the construction and maintenance of the new memorial park

to construct a landmark commemorating Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase, highlighting St. Louis's historical significance as the “Gateway to the West.”

Smith and Dickmann’s reframing of the project to focus on President Jefferson proved successful, leading President Roosevelt to sign a joint resolution in 1934 that created a federal commission to plan the design and construction of the memorial.

Despite its many positives, the plan required large-scale demolition of existing buildings along the riverfront, sparing only the Old Courthouse, Old Cathedral, and Old Rock House. This drew the ire of many city residents, particularly those who owned businesses or lived in the riverfront neighborhood.

To gain public support for the project, the mayor and other city officials portrayed the riverfront as outdated and rundown. However, the riverfront area was actually a bustling part of the city, home to 290 active businesses employing nearly 5,000 workers, as well as nearly 200 residences, most of which were rentals. With his background as a real estate developer, Mayor Dickmann promoted the project as one that would beautify the city, as well as stabilize and increase the downtown real estate market. He argued that clearing the riverfront would boost the value of surrounding properties, encouraging necessary economic development and creating investment opportunities for potential speculators. Claude Ricketts, chairman of the city's real estate board, reinforced this message, highlighting the financial benefits of increased property values post-demolition.

Meanwhile, critics saw through the scheme and pointed out how the project benefited real estate investors at the expense of the area's current inhabitants. Those opposed to the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association accused the organization of manipulating public opinion and overstating the problems of the neighborhood to justify demolition.

The 1935 Bond Election

Financially, the riverfront memorial project was ambitious and risky. It required a massive bond issue during significant financial hardship for the city. But if the city could win a bond election, the money would be used not only for land acquisition and area clearance but also to finance the construction of the memorial itself.

After extensive lobbying, Mayor Dickmann secured an initial $6.75 million commitment from the federal government (with an agreed total of $22.5 million) and planned a $7.5 million bond election for the city.

The campaigns for and against the bond were intense. Mayor Dickmann claimed the project would bring 5,000 jobs to the city (conveniently avoiding mention of the loss of 5,000 jobs when the companies in the area shuttered). Meanwhile, two groups, the Taxpayers Defense Association and the Citizens’ Nonpartisan Committee led by Paul O. Peters, described the plan as a scheme to enrich real estate interests at the public’s expense. They pointed out that the plan would decrease city revenues by about $200,000 annually and emphasized that the federal government had made no commitment to match the city's expenditure.

The results of the bond election on September 10, 1935, were astonishing: nearly 71% of the votes were in favor, allowing the bond to pass by a wide margin. However, the legitimacy of these results was quickly called into question.

A year-long investigation by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch uncovered over 46,000 fraudulent voter registrations, suggesting a deliberate attempt to manipulate the election outcome in favor of the riverfront project. Registrations were found at vacant buildings, hotels, and other non-residential addresses. The Washington Post even commented on the extent of the false registrations, indicating clear manipulation of the democratic process.

By 1939, the final appraisal for the condemned property reached nearly $7 million, marking a 65% increase over the previous year’s values—proving much of the opposition's fears about the overvaluation of the land.

Despite the controversies and allegations of fraud, a court ruling later determined that the city had entered into a legal contract with the federal government for matching funds, rendering the alleged electoral fraud moot. This ruling allowed the election results to stand despite the fraudulent votes.

Federal Funding Concerns

One significant obstacle in the riverfront project was securing federal funding. In November 1935, U.S. Attorney General Homer Stille Cummings declared that the government could not release the funds as planned under the Emergency Relief Appropriations Act of 1935 due to the project's local economic focus rather than broader public utility.

But that didn’t stop Mayor Dickmann. As a Democratic National Committeeman, Dickmann went straight to Washington, D.C., and threatened to withhold St. Louis’s Democratic vote for President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the upcoming elections if the necessary funds were not released. That’s right—the mayor of St. Louis essentially blackmailed the President of the United States to get his monument.

And just like that, Assistant Attorney General Harry Blair identified a legal workaround through the Historic Sites Act, facilitating the allocation of $6.75 million in federal funds. President Roosevelt finally authorized the funds on November 15, 1935.

Demolition and Opposition

With cash in hand, the city moved forward with its memorial project, which involved razing 37 blocks and 486 structures. This extensive demolition forced hundreds of residents and a vibrant community of artists and musicians to relocate. Despite the significant resources allocated to the memorial's creation, displaced small business owners faced inadequate support and limited relocation options. The demolition of numerous industrial and commercial buildings drove up the prices of other available locations, making it even harder for those displaced to find new spaces. Many people, including business owners and early preservationists, pointed out that the area wasn’t filled with slums and dilapidated buildings like city leaders claimed and noted that it was an important part of the city's early history. Among other things, the area was home to the city’s fur industry, which predated the founding of St. Louis. The riverfront also housed a considerable number of unique cast-iron buildings.

Among the most vocal opponents was Charles Peterson, an architectural historian who had already founded the Historic American Buildings Survey within the Department of the Interior. Appointed project planner for the new park with the National Park Service, Peterson was dismayed by the wholesale destruction of buildings he deemed historically significant. He viewed the demolition as a loss of cultural heritage that could have been integrated into new developments. Peterson was horrified to learn that the Historic Sites Act of 1935, used to legitimize the creation of the memorial, was now being used to sanction the destruction of hundreds of old buildings. As he lamented,

“We’re in the business of saving buildings, and here we are pulling them down, and wholesale! The biggest demolition the Park Service ever had.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Sigfried Giedion, a noted Swiss architectural historian, made fervent appeals to save the cast-iron buildings in particular. Giedion emphasized the structures’ architectural and historical importance, arguing they were essential to understanding St. Louis’s past and had no equivalent in other countries. In August 1939, Giedion made a final attempt to preserve these buildings, emphasizing their role as a "connecting link between the humble unpretentious warehouses of the Creole merchants and the modern skyscrapers," underscoring the narrative of the city's role in the expansion of the West. His efforts, however, were in vain as the city moved forward with its plans.

Preservation Efforts and the National Park Service

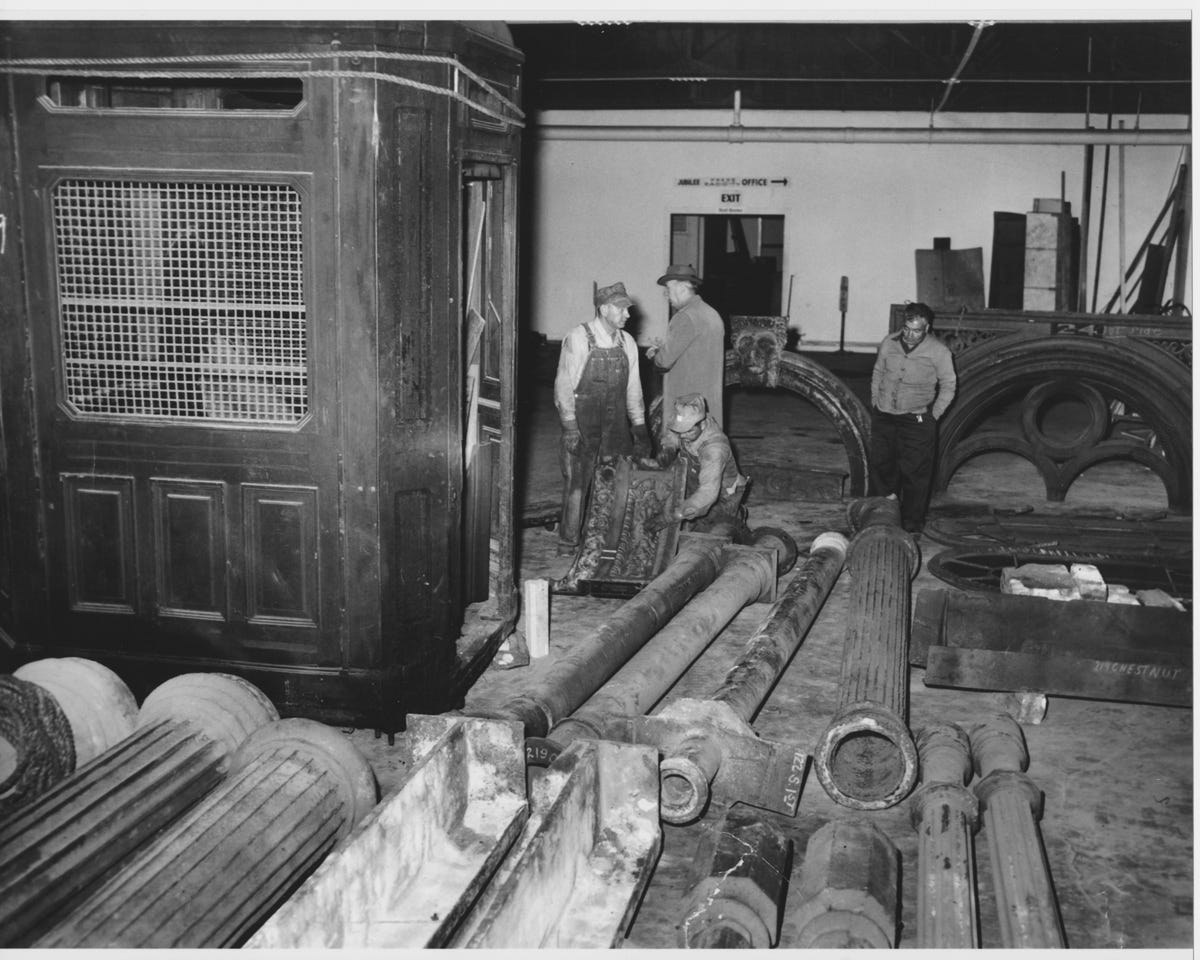

Before everything was reduced to rubble, the National Park Service made efforts to document and preserve some of the architectural elements of the buildings. All the structures slated for demolition were photographed, and staff created structural drawings for certain buildings. The plan was to establish an architectural museum as part of the memorial, including preserved building columns, cast-iron fronts, and other materials. To facilitate this, the architectural materials were stored at the Denchar Warehouse.

In 1958, the Denchar warehouse storing the original building materials had to be removed to grade the land for the memorial. Because plans to build an architectural museum had fallen apart, Park Superintendent Julian Spotts requested that the architectural fragments be given away. National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth approved the request, and letters were sent to local universities and museums offering the fragments at cost.

By September 1958, the National Park Service decided which objects it wanted to keep, and within the next few months, the Smithsonian Institution, the Missouri Historical Society, and other organizations hauled away selected items. In the winter of 1959, the Denchar Warehouse was torn down, ending all hopes of having a Museum of American Architecture on the memorial grounds.

The Case of the Jean Baptiste Roy Home

Originally built by fur trapper and explorer Jean Baptiste Roy in 1829 on land purchased from Pierre Chouteau Jr., the house at 615-17 South Second Street was the oldest dwelling in the city. Despite its historical significance, public interest waned after the riverfront district was obliterated, leading property owner A.L. Browne to order its demolition.

Efforts to save the building included interventions from the St. Louis Star-Times, Missouri Historical Society director Charles van Ravenswaay, and Harvard professor Kenneth J. Conant. Conant, president of the Society of Architectural Historians, toured the home in January 1947 and declared it worthy of restoration, stating, “It is part of the birthright of the city. You will be surprised how elegant a restoration would be made of this building.”

However, despite these efforts, demolition began on March 31, 1947. Lee Hess (of Cherokee Cave fame) bought the remains with initial plans to reassemble them for a museum, but these plans fell through, and the building stones were scattered.

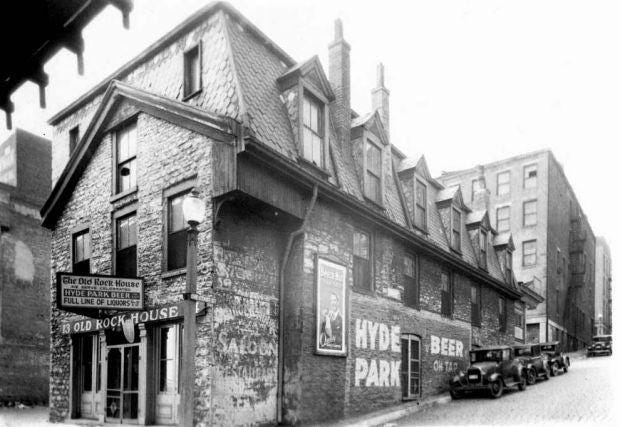

The Old Rock House: An Architectural Loss

Even older than the Roy house was the Old Rock House, built in 1818 by fur trader Manuel Lisa. It stood for over a century as a rubble-stone warehouse on Front Street (later known as Wharf Street and now Leonor K. Sullivan Boulevard), a testament to St. Louis’s early commercial history. Purchased by James Clemens, Jr. in 1828, the building served various functions over the next sixty years, including a sail loft that manufactured canvas tops for covered wagons, an ironworks store, and a produce commission house.

In 1880, it was converted into a saloon, and during the 1930s, it gained popularity as a nightclub featuring African-American performers. Ann Richardson, known as “Rock House Annie,” drew crowds of suburbanites who came to hear black music played by black musicians. When the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial was established in 1935, the Old Rock House was the oldest standing building in St. Louis.

The building's historical significance and unique architectural features made it a prime candidate for preservation. In 1940, the last tenants were evicted, and the Park Service obtained a Works Project Administration grant to convert it into a museum of the historic St. Louis fur trade. Despite this, plans in the 1950s to relocate the elevated railroad tracks along the river doomed the Old Rock House, as it could not be moved as a unit due to its construction on a limestone outcropping. The structure was disassembled in 1959, but by 1965, much of the Old Rock House was missing and presumed lost. (None of the stones were used in the new Old Rock House event venue.)

A Parking Lot

By the mid-1940s, almost all buildings were gone (and others in the vicinity, such as the Merchant’s Exchange, would go soon thereafter). Until they started construction of the Gateway Arch in 1963, however, the area where so many buildings once stood was nothing more than a parking lot.

Was It Worth It?

The transformation of St. Louis's riverfront was a complex and controversial project. While the project ultimately succeeded in creating the Gateway Arch—a magnificent monument that brings joy and pride to many (including myself)—it’s difficult to reconcile its grandeur with the extensive demolitions that preceded its construction. In order to gain the Arch, St. Louis lost a significant part of its history and a vibrant neighborhood that could have been revitalized.

One commentator suggested that, rather than erasing this historic area, it could have been transformed into something as grand and culturally rich as the French Quarter in New Orleans. Instead, the decision to demolish the riverfront district resulted in the destruction of businesses, historic buildings, and a lively community, highlighting a profound loss amidst the creation of an iconic symbol.

In the end, was it worth it? For me, it’s a hard call. I’d love to know what you think.

Timeline

April 11, 1934: the State of Missouri incorporated the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association (JNEMA)

June 15, 1934: President Roosevelt signed the Joint Resolution establishing the United States Territorial Expansion Memorial Commission (USTEMC)

April 10, 1935: The Governor approved H. B, 445, authorizing the City of St. Louis, upon approval of the voters, to issue bonds up to $5 million “for the purpose of providing funds to pay by way of assistance to the US, or its qualified authority… in order to induce the location and establishment within such city or such park or plaza.”

April 30, 1935: The Board of Aldermen unanimously adopted the Resolution, committing the City to hold the bond issue election and to take necessary steps to vacate streets and alleys in the Memorial area.

May 1, 1935: USTEMC approved plan — boundaries, historical significance, architectural competition, and estimated total cost of $30 million

June-July 1935 City of St. Louis passed the necessary ordinance permitting its citizens to vote upon a bond issue to contribute up to $7.5 million for the memorial

August 21, 1935: President signs Act on “Historical Sites, Buildings, Objects, and Antiquities”

September 10, 1935: Citizens of St. Louis passed the $7.5 million bond issue by more than a ⅔ majority

September 23, 1935: Mayor approves ordinance directing tissue of $7.5 million bonds

November 3, 1935: Missouri Supreme Court sustains validity of bond issue

December 21, 1935: President Roosevelt signs Executive Order 7253 designating the Secretary of Interior to acquire and develop Jefferson National Expansion Memorial with the allocation of $6.75 million of federal funds (from Public Works Administration) to be matched by $2.25 million contributed by St. Louis

Jan-March 1936: Injunction suits in state courts to restrain the city from proceeding with memorial decided and suites dismissed

February 1, 1936: Mayor Dickmann approves an ordinance authorizing payment of $2.25 million to the US government

June 22, 1936: National Park Service establishes office in St. Louis for Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

June 24, 1936: The District Court of the US for the District of Columbia dismisses a suit to enjoin the National Park Service from proceeding

August 17, 1936: US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia grants a temporary injunction preventing land acquisitions

March 8, 1937: The US Court of Appeals affirms the district court’s decree and denied the injunction

June 1, 1937: US Supreme Court terminates the case and dissolves the injunction

June 1937 – July 1938: 40 petitions (one for each block) are filed in the US District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri to condemn lands in the area for Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

July 1, 1937: Mayor Dickmann approves ordinance authorizing mayor and comptroller to deed Old Courthouse to US Government

July 1937 – October 1938: New cases are brought to halt the project; all eventually decided in favor of the government’s right to proceed

June 14, 1939: Funds totaling $6,183,480 are deposited in the Registry of the US District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri as the reasonable value of the lands to be acquired for the Memorial under a Declaration of Taking and title to 37 blocks, and portions of 3 others were thereby vested in the US

January 1938 – June 1939: Commissioners appointed by the US District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri return an aggregate appraisal award for the area under condemnation of $7,012,554

January 1940: Demolition contracts covering the entire area are let, which should complete the removal of the buildings by Spring of 1941

March 15, 1940: Of 479 parcels under condemnation, 78% are settled satisfactorily as to price in agreements with owners

1936 – 1940: Historical and planning studies are made concurrently with the process of land acquisition

December 1940 – November 1941: Presidential approval is granted for Works Projects Administration projects for restoring the Old Rock House; the general improvement of the Memorial Area; the construction of National Memorial Drive (widening Third Street); partial restoration of the Old Courthouse; preparing museum exhibits; and constructing new facilities in the Memorial area

December 1, 1941: Offices of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and National Park Service are moved into the south wing of the Old Courthouse

May 1942: Demolition of all buildings to be removed from the memorial area is completed

As always, thanks for reading and for supporting Unseen St. Louis! If you’re not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribing for free means you’ll always get the latest article and update delivered right to your email.

And if you’re already a subscriber, I’d love for you to consider upgrading to a paid subscription to show your support for St. Louis history and to keep this work sustainable. (I’m trying to purchase a house in STL City, and every dollar counts!)

Select Sources

A City Plan for St. Louis, St. Louis: The Civic League of St. Louis, 1907.

Author interview between Tracy Campbell and NPR’s Scott Simon, Gateway Arch 'Biography' Reveals Complex History Of An American Icon, May 25, 2013.

Mary Bartley, St Louis Lost: Uncovering the CIty’s Lost Architectural Treasures, St. Louis: Virginia Publishing, 1998.

Tracy Campbell, The Gateway Arch: A Biography. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

Thomas C. Grady, The Lost St. Louis Riverfront, 1930-1943. St. Louis: St. Louis Mercantile Library, 2019.

Alex Ihnen, What “The Gateway Arch” by Tracy Campbell Tells Us About St. Louis, NextSTL, May 31, 2013.

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York: Vintage Books, 1992. (Originally published in 1961).

Walter Johnson, The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States, New York: Basic Books, 2020.

Fred Kaplan, The Twisted History of the Gateway Arch, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2015.

Bob Moore, An Architectural Museum on the St. Louis Riverfront, National Building Arts Center website.

Tim O'Neill See what had to be cleared before they built the Arch, St Louis Post-Dispatch, April 11, 2024.

Kimberlee N. Ried, A Gateway to the West, Prologue Magazine, Fall 2016, Vol. 48, No. 3.

St. Louis Globe-Democrat and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Mark Tranel, ed. St. Louis Plans: The Ideal and the Real St Louis, The Missouri Historical Press, 2002.

Teens Make History Apprentices, What the Arch Cost St. Louis, Missouri Historical Society, February 4, 2021.

Carolyn Hewes Toft, The Arch Grounds and the Old Rock House, Landmarks, 1996.

Booklet by Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association, May 1935, Missouri Historical Society Collections.

Newspaper clippings and other ephemera, Missouri Historical Society Collections.

My compliments on a thoroughly researched and well-presented article.

Jackie, congratulations. You are one of the few in this city who has a more complete, detailed understanding of what happened on the riverfront.