Welcome to another edition of Unseen St. Louis, where I examine unusual or largely-forgotten moments in history. In light of record-setting rainfalls and flash flooding over the past couple of weeks, I thought it would be timely to examine how almost 100 years ago, St. Louis took big steps to prevent flooding along the edge of the city.

What is the River Des Peres?

The River Des Peres is a once-idyllic small river that flows through St. Louis city and county. The main river channel starts at N. Warson Rd. just north of Olive, runs as an open stream through University City, and goes underground just west of Kingsland, a couple thousand feet from where it flows under Forest Park. It then re-emerges as a channelized river just east of Macklind at Manchester. The river bottom is now concrete, with the banks lined with big chunks of limestone rip-rap, and it flows through neighborhoods along the boundaries of St. Louis City until it reaches the Mississippi in south St. Louis.

And it has always been controversial

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch is filled with late 19th century and early 20th century accounts of people drowning in the river, of the stench of the water, often filled with sewage, of the mosquitos and disease blamed upon the waters, and most of all, the devastating floods that were a regular part of life near the river.

Below is a poem published in the paper back in 1894. (On YouTube there’s a modern tribute to the river if you prefer).

For decades citizens and city leaders called for something to be done about the problematic waterway, but finances, differing opinions, and a world war got in the way.

The early days

The name River Des Peres comes from the French for “of the fathers,” and honors the Jesuits who settled along its banks near the Mississippi River.

One segment of the river ran through what would become known as Cheltenham, south of Forest Park. As I describe in a separate article, this area was popular with early settlers who chose to make their homes near the river and nearby sulphur spring. (As I explain, this area would become home to clay mining and factories as well as the first train station west of downtown St. Louis).

1904 World’s Fair

In 1876, the river was considered scenic and was considered a feature in the newly-opened Forest Park. But things soon changed as the city grew and the waterways, including the River Des Peres, began to be used as sewers.

When city officials began to plan the 1904 World’s Fair in the park, they anticipated huge crowds. Wanting the city to be a gleaming showcase for international visitors, the officials quickly realized that fairgoers would not appreciate the stench of an open sewer running through the park.

As a result, work began in early 1902 to dig a channel for the river, which would then be covered for the duration of the event. They enclosed the river in a wooden tunnel through the park at a cost of $125,000.

A Permanent Plan

For those who lived in the River Des Peres valley, any significant rainfall could spell disaster. Flooding, river rescues, and loss of homes and other property were regular occurrences. In August 1915, thanks to a hurricane the city received over 7 inches of rain, causing significant flooding.

As described in the Post-Dispatch, the flooding cut the city off from the county. Floodwaters turned the Jefferson Memorial in Forest Park into an island, as much of the park was under 10 feet of water. Houses in Maplewood flooded to the second floor.

In that one flood, 11 people died, and over 1000 homes were destroyed.

For years city officials tried to do something about the river, but it was a costly endeavor and the city residents refused to support a bond project. Finally in 1922 Mayor Henry W. Kiel had a billboard constructed on which he said,

“Think this over! What other big city would have an open sewer running through a fine, big park?”

That was enough for voters to finally approve $11 million in bonds to address the problem.

Channelizing the river

After the bond measure passed, W. W. Horner, chief engineer for the Board of Public Service, divided the river into sections lettered A through J to break the work into ten chunks, starting with A in 1924 and completing J in 1933. Workers drained the river and installed sewer pipes. Nine miles of the river flowed underground in 58-foot-wide tunnels before emerging near Macklind Avenue.

Later, between 1933 and late 1940, workers hired by the city and the Works Progress Administration placed the stone along the banks to prevent future erosion.

Ultimately, the River Des Peres channelization project was designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1988.

Pushing the problem downstream

Burying the river through Forest Park, and for a little ways south, helped solve the problem of flooding in the wealthier neighborhoods and within the park itself, but as anyone who lives near the river channel in South St. Louis can tell you, it didn’t totally solve the issues of stench, mosquitoes, or flooding.

Most heavy rains over the city that cause runoff will cause the river to swell. In fact, during our recent rains (8.64 inches on July 26th being our all-time one-day record, though we got several inches more over the next two weeks), the river turned from a trickle to white water rapids in moments. Under such conditions, the river can jump its banks for a short time. But it’s Mississippi River flooding, causing water to back up into the River Des Peres, that leads to the worst inundation into local neighborboods.

There have been several years when the river has jumped its banks and spilled into neighborhoods, particularly during record-setting flooding back in 1993.

More recently, the Riverfront Times documented some of the flooding in 2019.

It’s worth considering architectural historian Michael Allen’s take on the issue:

Among the most significant consequences of the River Des Peres project has been continued flooding of the southwestern part of the river, which has overflowed carrying stormwater from more wealthy western neighborhoods. Heavy flooding in 1973 overwhelmed governmental resources, so private citizens in the affected middle-class areas built their own levees along the open channel to prevent further flooding. These levees held for a flood in 1982-1983 and still stand today, although they did very little to help during the huge flood of 1993.

The River Des Peres and the environment

Until relatively recently, the River Des Peres received little respect. It has long been a place where people tossed old appliances, tires, and even cars. Near its approach to the Mississippi, a number of industrial plants occasionally dumped oil or chemicals into the water. In one case, Monsanto was the cause of a fuel oil spill in 1977, while two years earlier, an unknown source poisoned 5000 fish in the river. The Missouri Department of Conservation reported in 1976 that the river was “grossly polluted,” a situation that caused little concern at the time because the water was not used for drinking water, fishing, or recreation.

Despite the pollution, wildlife—from ducks and geese to fish, snakes, turtles, and frogs—have always found a home in the river, and rats routinely take up residence in the underground tunnels.

Legacy

It’s a shame that the designers of the flood abatement project didn’t consider the environmental impact of their concrete river channel or other ways to protect it as a natural stream. No effort was made to mitigate run-off into the channel or make the river aesthetically-pleasing to the city’s residents.

Obviously, St. Louis could have built needed storm water and sewer lines without disturbing the River Des Peres, although that would certainly have been more expensive and less impressive.

In a failed attempt to turn the river into something other than an eyesore, Mayor Alfonso J. Cervantes proposed in 1972 that they turn part of the lower river (between Lansdowne and Morganford) into a recreational lake for boating. The plan fell through when local residents complained about the potential for traffic and crowds in their neighborhoods, none of which had been designed for such a purpose.

Only in Forest Park has anything been done to honor the River Des Peres. Starting in 1993, the park underwent a significant redesign that turned existing water features into an approximate stand-in for the original river, although 100% of the actual river remains underground.

Despite the river not being the idyllic stream of yesteryear, it can make for a pleasant outing (if you give it a chance, it has its charms). Although you still won’t want to play in the water, it seems significantly cleaner than it was in the 1970s and 1980s—perhaps because some factories have relocated, while others follow more stringent EPA laws.

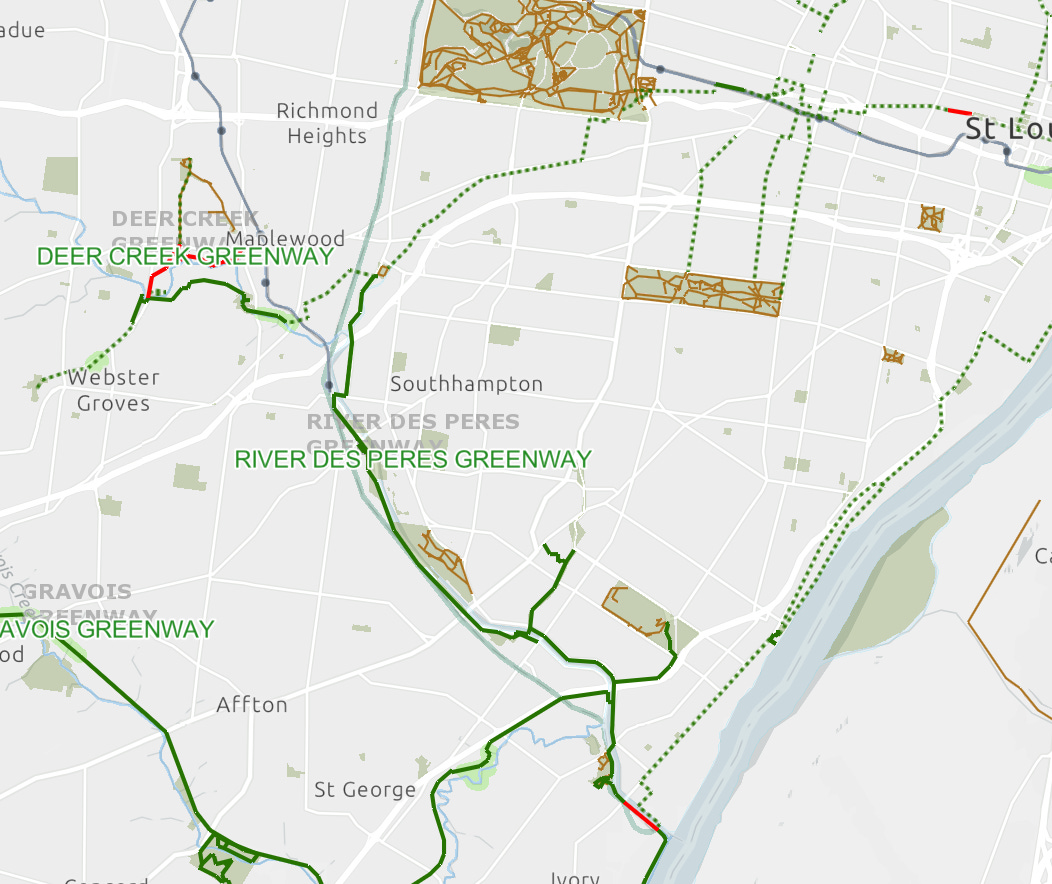

Today the majority of the river is part of the extensive Great Rivers Greenway, allowing hikers and cyclists to follow a 9.36-mile paved trail along the river. (You can download a detailed map from their website.)

And if nothing else, you can go visit my favorite little bridge over the river at Sulphur Ave. that started my journey through lesser-known moments in St. Louis history.

Thanks for reading this history of the River Des Peres. If you enjoyed this, I encourage you to take a look at the other history articles I’ve shared here. And be sure to share it with your friends!

Sources

Michael Allen, The Harnessed Channel: How the River Des Peres Became a Sewer, 2010.

Jeannette Batz, A Sewer Runs through It, Riverfront Times, 6 December 2000.

Jackie Dana, A little but mighty bridge (my article about a bridge over the River Des Peres)

Jackie Dana, Finding the beauty within an industrial wasteland (my article about the area just south of the River Des Peres, now near Hampton and Manchester)

Chad Garrison, Rare Glimpse Into Underground Tunnels of River Des Peres, Riverfront Times, 25 October 2011.

St Louis Post-Dispatch

10 Jan 1902

12 Jan 1916

31 July 1978

River Des Peres, 1915 (23 July 2012)

River Des Peres (Wikipedia)

Wow, this was really great!

Interesting and extensive historic overview. Thank you!