How a St. Louis tavern was part of the plot to kill Martin Luther King Jr.

The history of a former tavern on Arsenal St. in Benton Park

It’s not every day that you walk into a coffee shop and walk out with a piece of tangible history. Last fall, I wandered into Spine Indie Bookstore & Café at 1976 Arsenal St. in St. Louis, intrigued by the perfect pairing of coffee and books. After chatting with owner Mark Pannebecker, I discovered that this pleasant and welcoming space (which I highly recommend!) has a bit of a dark but fascinating past involving Martin Luther King Jr.

Anyone who lives in an old house probably can relate to this idea that buildings have histories, and if they could only talk, they would have some epic stories to tell us about their previous residents. Commercial buildings house the same ghosts of businesses that came before, along with all the joy and baggage that such history holds.

But since buildings can’t talk, it falls upon us mortal being to tell the stories on their behalf. And with that, let’s take a look at the history of the building at 1976-82 Arsenal and consider why we care about historic buildings as a whole.

The star of our story

The building on Arsenal Street in south St. Louis was built in 1889 by Christian Shollmeyer. It remained in the family until at least 1935. Like many buildings of its era, it had both a commercial storefront on the main level and apartments on the upper floors.

The commercial area was a tavern in the 1930s. A classified ad in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch indicated it was for sale at a “reasonable” price in 1937, and by 1938, the presumably new owner, Michael Reichert, was fined for selling alcohol on a Sunday.

Through the years, the Shollmeyer building housed a shoe repair shop, a beauty shop, a grocer, and an upholsterer. According to Mark Pannebecker, legend has it that it was also a brothel and speakeasy that utilized the English Cave underneath (see below) as an emergency escape route from police raids.

Despite its many incarnations, it was again operating as a tavern by 1960. In 1967 it was purchased by John Larry Ray and his sister Carol Ray Pepper, who turned it into the Grapevine Tavern, described by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch as a “hardscrabble St. Louis tavern… a good-sized place with a pinball machine, shuffleboard and an ornamental tin ceiling.”

Since its time as a tavern (the Grapevine shuttered in December 1968 after John Ray was convicted of robbing a bank in St. Peters), the Shollmeyer building has continued to host a variety of businesses. In the 1970s it was home to a company that sold industrial safety glasses, and in the 1980s, after being boarded up and vacant for some time, it became a gallery for the New Arts Gallery and Studios.

Today the Shollmeyer building houses Spine Indie Bookstore and Cafe, as well as residential apartments on the main and upper floors.

Benton Park & English Cave

Before continuing on with the story of the building, it’s worth a brief digression to talk about its most important neighbors. One of those neighbors is Benton Park, which also gives its name to the neighborhood as a whole.

In the early days of St. Louis, the land served as the St. Louis City Cemetery from 1833 or 1842 to 1859 or 1865 (sources differ on dates). Because the city outlawed cemeteries within the city limits, as St. Louis expanded, it could not be used for its original purpose. After the graves were relocated to the Quarantine section of Arsenal Island in 1859 (this frequently happened to graves in early St. Louis history), the land was turned into a park named after Senator Thomas Hart Benton. Edward Krausnick, a horticulturist and park superintendent, designed the park and added two lakes, a fountain, and stone bridges, and planted rare trees and shrubs.

In the early days, the pond would periodically—and mysteriously—drain underground. It turned out that the pond had been built over English Cave, a cave system that stretches under the park, our architectural hero, and across the alley to the English Cave Community Garden. (For more, I briefly discuss English Cave in my article on brewery caves.) Eventually, they redesigned the ponds (eliminating one of them) and lined the remaining pond with concrete to prevent further drainage into the cave, and now the main pond is regularly stocked with fish. And Benton Park was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

How the Shollmeyer building connects to MLK Jr.

When I visited Spine for the first time, I learned about the connection the building had to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. As it turns out, back in the late 1960s it had been the Grapevine Tavern, and it was owned by the brother of James Earl Ray, the man convicted of killing King.To be honest, before that moment I had no idea that the Ray family was local to the St. Louis area.

So in case you’re just as much in the dark as I was, here’s a quick rundown of James Earl Ray. He was born in Alton, Illinois, in 1928. His family moved around a lot, jumping from town to town in Illinois and Missouri, as his father had escaped from a prison farm (essentially a halfway house) in 1923 and remained a fugitive until his death in 1986. James Earl enlisted in the Army after WWII but received a general discharge in 1948 (under questionable circumstances that involved him shooting a man). At any rate, he returned to Alton, getting involved in petty crime in the St. Louis metro area and traveling to Chicago and LA, not insignificantly having a black girlfriend at one point. He drifted between cities, engaging in petty crime, and serving short prison stints, before finally returning to St. Louis in 1959.

Not long after he arrived in St. Louis, he robbed a Kroger grocery store, for which he was sentenced to 20 years at the Missouri State Penitentiary. After two unsuccessful escape attempts, he succeeded on breaking out on April 23, 1967.

As petty criminals in southern Illinois, the Ray family knew and regularly encountered members of the Chicago Mob. While John Ray kept his distance, James Earl was much closer to them, and regularly associated with members of East St. Louis boss Buster Wortman’s crew.

The Grapevine Tavern enters the story

In addition to all of the other moments in its history, as noted above, the building was once the Grapevine Tavern, owned by John Ray. And depending on whose story you believe, it may have played a key role in a conspiracy to assassinate Martin Luther King Jr.

In the fall of 1967, John Ray and his sister Carol opened the Grapevine Tavern. John Ray initially planned to call his new tavern “Jack's Place,” but instead chose Grapevine, an allusion to the prison grapevine.

Earlier in 1967 James Earl Ray had escaped from the Missouri State Penitentiary, and then gave John $25,000—a small fortune back then, especially for an escaped con with no job or resources. We’ll come back to that money later.

Grapevine Tavern opened on New Year’s Day, 1968 in a neighborhood that was extremely white, and, as John Ray put it in an interview, “pretty redneck.” George Wallace’s presidential campaign office was nearby, and the area also was home to a local White Citizens’ Council, a series of groups organized as a response to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, and that existed to harass, intimidate, and threaten Black people at the polls and elsewhere. And indeed, as the Riverfront Times (RFT) describes,

“Almost immediately, [the Grapevine Tavern] became a magnet for government informants and two-bit criminals, and a popular watering hole for supporters of segregationist and American Independent Party candidate George Wallace.”

And this was with John Ray’s total support. In a comment reported in the RFT, Ray said, "We had his buttons and posters and everything. I voted for Wallace. Now, James — he always liked Nixon."

According to John Ray, St. Louis police agreed to leave the Grapevine alone and allow them to stay open a couple of extra hours if John agreed to display Wallace's pamphlets at the tavern, and he was happy to oblige. As St. Louis Magazine noted,

“The Wallace message resonated in South St. Louis. Wallace supporters and Citizens Council types congregated at the Grapevine Tavern, on Arsenal, every afternoon to talk about the campaign. The bar also served as a sort of criminal temporary-employment office. Ex-cons would show up there and find themselves a “job,” listen to racist political speeches and drink themselves drunk.”

Although Ray owned and ran the Grapevine, he also had tenants who rented the sleeping quarters above the tavern. According to the Post-Dispatch, “the upstairs roomers and the [Wallace] campaign workers were not enough to make the tavern a financial success.” When Ray was arrested for robbing a bank in St. Peters, his financial troubles were seen as a motive, although Ray maintained that he had nothing to do with that robbery. Either way, he was sent to prison, and the Grapevine Tavern closed in December 1968.

Was there a St. Louis-based conspiracy to kill King?

Now it’s time to bring the various threads together. We know that the building on Arsenal housed James Ray’s Grapevine Tavern, home to racists and plenty of white supremacists. But is this where James got the idea to shoot Martin Luther King?

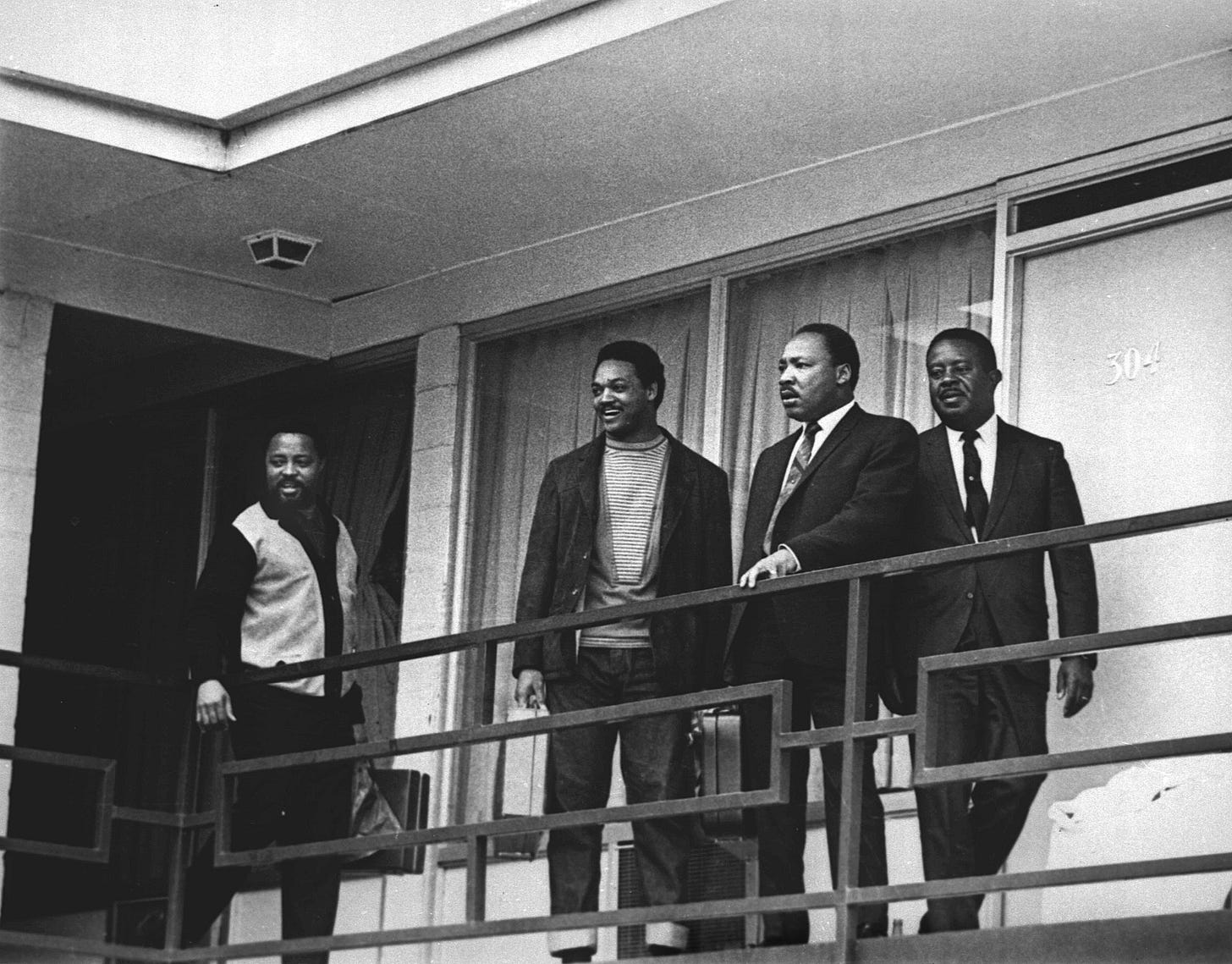

There are a lot of theories about who shot Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, TN. Two of the most prominent include:

James Earl Ray was guilty and acted alone or as part of a conspiracy that was motivated by racism or greed (a bounty), or both;

Ray was innocent and a patsy, as part of a conspiracy to conceal the true assassin’s identity.

Both of these theories about King’s murder tie back to the Grapevine Tavern on Arsenal (as I will note with italics), though in different ways.

Theory #1 (The official theory)

Initially, James Earl Ray confessed to killing King (a confession he later retracted, saying he had been pressured into confessing), and was tried and found guilty of King’s murder, which was portrayed at the time as a racist act.

Because that decision didn’t sit well with many people, the House Select Committee on Assassinations opened a new investigation in 1976 into the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.

In its 1978 report, the HSCA concluded that James Earl Ray killed King in order to collect a $50,000 bounty. This reward had been offered by a patent attorney named John H. Sutherland, who had been involved in both the White Citizens Councils and in Wallace’s 1968 presidential campaign. Sutherland’s associate John R. Kauffmann, another white supremacist, had supposedly approached James Earl Ray at the Grapevine Tavern to make his offer.

As many have pointed out, the story is a bit suspect. It came from St. Louis auto parts dealer and art thief Russell G. Byers, brother-in-law to Sonny Spica (James Earl’s former Mob cellmate). Several years before, Spica had told the FBI that it was well-known in St. Louis that there was a $50,000 bounty on King’s head, and he claimed Kauffmann (a friend of his) and Sutherland approached him to kill King, but he had declined.

According to Byers, it was then that they approached James Earl Ray.

The HSCA suggested the men met Ray at the Grapevine Tavern to engage him in the conspiracy to kill King, but both Ray brothers always denied this ever happening. The Post-Dispatch reported back then that John Ray denied “that any such offer was made to his brother.” Furthermore, for years James Earl Ray vehemently denied ever having been approached by anyone from the Wallace campaign.

Both Kauffmann and Sutherland had died before the HSCA convened, so conveniently, they were not available to be questioned by the Committee.

Despite the holes, this theory remains the prevailing one to this day. According to the US government, Ray shot King from the bathtub in a neighboring hotel, escaped by car, and eventually was captured and convicted after Ray made a full confession of his guilt. But it is an uneasy truth. In the original trial, they made Ray out to be a racist, but over time that was proven false. So they had to make it about money, which was a proven motivation in Ray’s life.

Conrad “Pete” Baetz, a Madison Co. sheriff’s deputy who assisted with the HSCA investigations, pointed out, “We never could figure out why Ray did it,” Baetz said. “He wasn’t a racist to the point of assassinating somebody. He never did anything in his entire life that there wasn’t a buck behind…” (St. Louis Post-Dispatch April 4, 1993).

Theory #2 (John Larry Ray’s theory)

According to John Ray, his brother was an innocent patsy of a deep conspiracy involving the feds (the CIA and FBI) and the Chicago Mob.

In his book Truth at Last, John points out that in the 1950s and 1960s, this wouldn’t have been terribly surprising as it was an open secret that the Mob and the Feds were known to have common interests and worked together, such as was seen with Castro’s Cuba. And given what we know about LBJ’s dislike of King due to the latter’s anti-war stance (the Vietnam War having destroyed LBJ’s political career), and the fact that the government saw King as a Communist agitator, it’s not impossible to believe this theory.

So how did this play out? According to John, James Earl was pretty friendly with the Chicago Mafia. As noted above, he had hung out with members of the Mob before going to prison, and at the MO state pen his cellmate was Sonny Spica. (John Ray admitted in his biography that through this period he never could determine if his brother had joined the Mafia or not).

After his escape, James associated with Obie O’Brien, who was close to East St. Louis mob boss Wortman. Obie sent James out on a number of missions after James escaped prison, including trips to New Orleans and California. John Ray believed that while in prison, Spica convinced his brother that there would be a big job waiting for him if he escaped, and then Obie gave James $50,000, with half of it going to help John open the Grapevine Tavern. John claimed that the money was connected to a diamond heist, and had nothing to do with Martin Luther King, Jr. John believes Obie was working with the government to ensure James Earl was in the right place, and in possession of weapons, to serve as a patsy when someone else pulled the trigger.

As John put it, just before the assassination, James “said that he was going to ‘do a job,’ but didn’t know what was going down,” and he didn’t have a good feeling about it. That’s when the brothers agreed that James would pay back the Mob’s $50,000.

And during his trial and the subsequent investigation, the source of the $50,000 was a hot topic. James apparently lied to the feds, telling them first it came from a grocery heist and then that he had stolen it from a pimp. But the version where Obie gave him the money never made it into the official record, because one thing the Rays never did was inform on the Mob. As John Ray put it, “This fabrication meant that there would likely be no record of where he had actually gotten the money: Buster Wortman and Obie O’Brien, who got it from the Chicago Mob, who got it from a select group of clandestine operatives within the Central Intelligence Agency.”

But this theory has never risen to the same prominence as the first one, told by the government. And it makes sense that the government sticks to the story told by Byers. As James Ray said, the feds “made certain that the plot to kill King stayed in St. Louis with those two dead guys and that it didn’t cross the river to East St. Louis, with its ties to Chicago.” In other words, they kept Wortman and the Mob out of the picture entirely.

It’s noteworthy that King’s own family and closest associates have doubted Ray’s guilt (or at least that he acted alone) for a long time. So although this has all been played out in court and official investigations, many people are dissatisfied with the official theory of Ray’s involvement.

At any rate, the point may be moot now. James Earl Ray died in jail in 1998 at age 70. John Larry Ray died in 2013.

The good news

Whether James Earl Ray was recruited to shoot King at the Grapevine or not will probably never be known, but regardless of the truth, the Grapevine will always be a central part in the plot to assassinate Martin Luther King Jr.

As tragic a tale as that is, it’s also more than 50 years in the past. Returning to the present, it’s nice to note that the Benton Park neighborhood is more diverse and tolerant than it was back in the day, and it’s inconceivable that white supremacist campaign offices would be welcome today.

Indeed, Spine today is everything that the Grapevine was not: it’s a welcoming and vibrant space bubbling with creative energy. It hosts open mic nights with music and comedy and storytelling, history talks, writing groups (my group Write It Already STL currently meets there every Friday!), and more.

And as I dove into the history, I take inspiration in recognizing how a building can go from a speakeasy and brothel to a tavern bankrolled by the Chicago mob to a bookstore and cafe welcoming to everyone. Maybe time can’t heal all wounds, but we can certainly give it our best shot.

With all of the old and currently vacant buildings and storefronts in the city, seeing Spine’s transformation offers hope for others. I think about the Railway Exchange building that once was the home for the Famous-Barr department store but now lies fallow and deteriorating, forcing the city to condemn it.

As I hope I’ve demonstrated in this article, even the most unassuming brick building in an average neighborhood can represent an important history. That’s why saving St. Louis’s built environment—and the history it contains—is critical if we want to understand who we are and how the city came to be.

Thanks for reading Unseen St. Louis. If you found this article interesting, please consider sharing it with a friend or on social media.

Sources

Ellis Conklin, John Ray used to own a tavern in Benton Park. Now he lives in Quincy and dabbles in conspiracy theory, The Riverfront Times, April 2, 2008.

Investigation of the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr, Hearings Before the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives, Ninety-fifth Congress, Second Session, By United States. Congress. House. Select Committee on Assassinations, James Earl Ray, 1979 [Google Books].

James Earl Ray St. Louis Connections, St. Louis City Talk, April 4, 2020.

JFK Assassination Records, Findings on Martin Luther King, Jr. Assassination, National Archives.

Tim O’Neil, How the feds discovered that Martin Luther King's killer was a small-time St. Louis robber, St. Louis Post-Dispatch April 22, 2022.

W. Pate McMichael, The Plot to Kill a King, St. Louis Magazine, September 19, 2009.

Phillip F Nelson, Who Really Killed Martin Luther King Jr? The Case Against Lyndon B. Johnson and J. Edgar Hoover, 2018.

John L Ray and Lyndon Barsten, Truth at Last: The Untold Story Behind James Earl Ray and the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Lyons Press, 2008.

Report by a Missouri Man Suggests Plotters Sought Murder of Dr. King, The New York Times, July 26, 1978.

C. D. Stelzer, A deep dive into the 1978 House Committee on Assassinations’ conspiracy theory on the murder of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., STL Reporter (originally published in The Riverfront Times, April 8, 1992).

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, including:

November 17, 1978

November 30, 1978

July 17, 1979

April 4, 1993

April 22, 2022

White Citizen Councils, The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford.

Harold Weisberg, Frame-Up: The Martin Luther King-James Earl Ray Case, 1971

The book "Killing the Dream" by Gerald Posner delved into Rays life in and around STL. He comes across as a loser, liar, and small time hood, not to be trusted in anything he said.

I interviewed with Russell for a home health position awhile back. The vibes were off and I was thoroughly freaked out when I came home and researched him.