The Odyssey of Hardscrabble

How the handbuilt log cabin of Ulysses S. Grant has proven as resilient as its builder

Welcome to a long-overdue article from Unseen St. Louis. The story of Ulysses S. Grant’s traveling Hardscrabble cabin has been on my mind ever since Amanda Clark of the Missouri Historical Society mentioned it in a talk a couple of years ago, but life’s distractions kept it on the back burner. At last, here’s the tale of Grant as a farmer, and the journey of his hand-built log cabin, nicknamed Hardscrabble, after his death. I hope you enjoy this story!

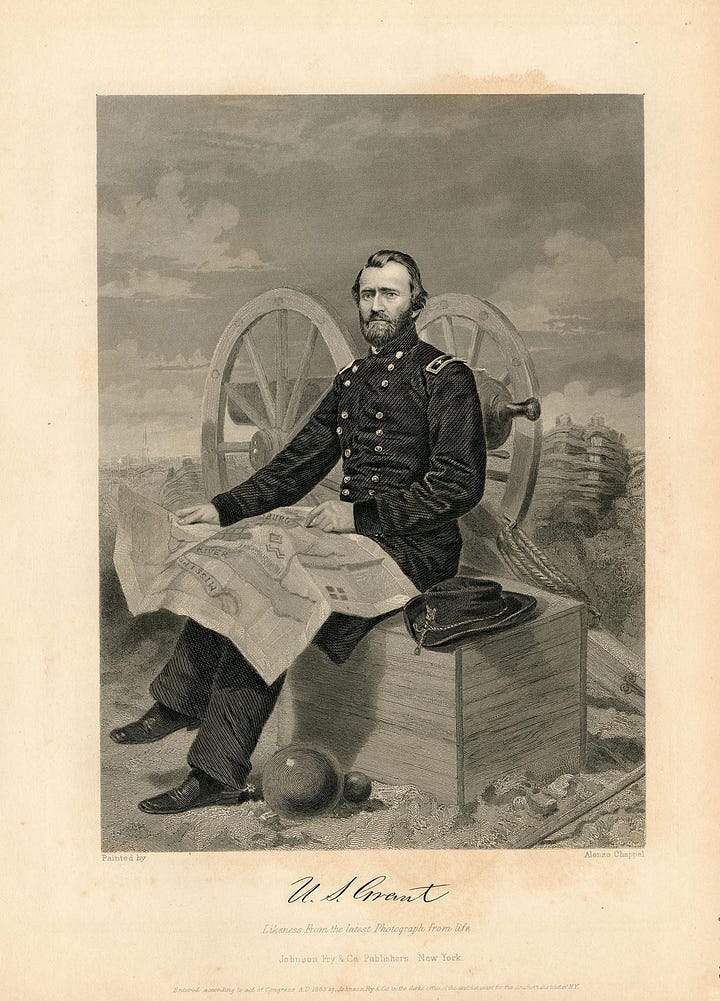

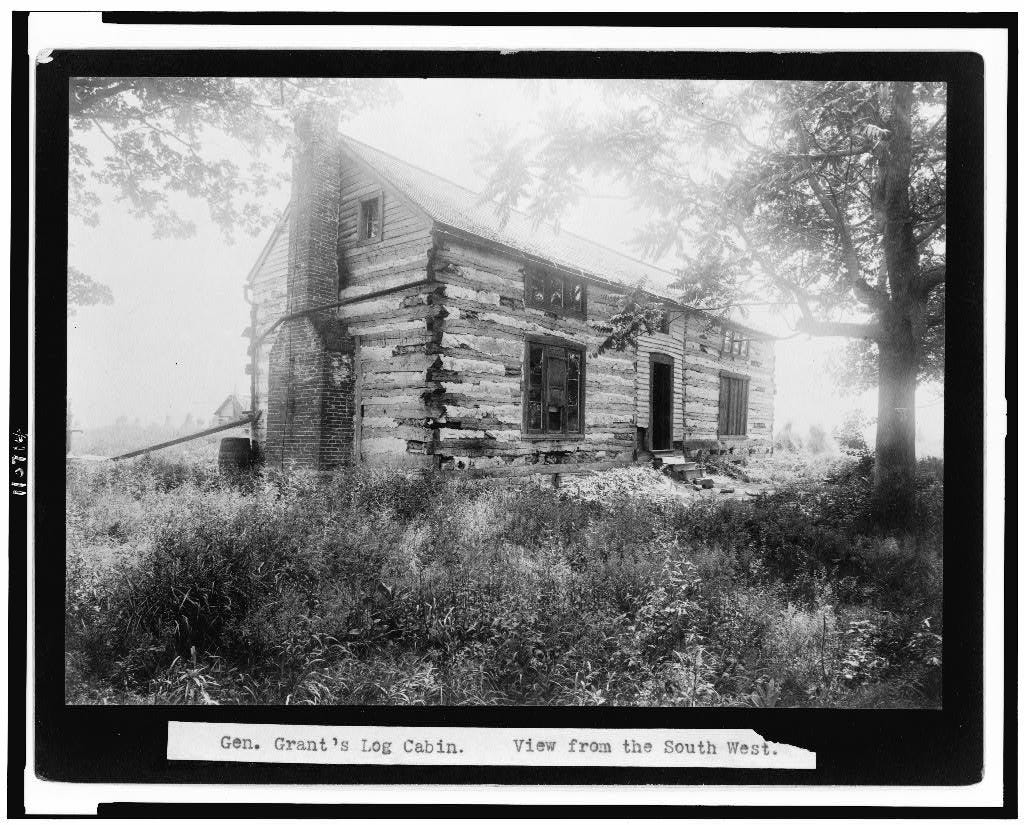

Before Ulysses S. Grant rose to national prominence as a celebrated general and then the 18th President of the United States, his life was marked by personal struggles here in St. Louis. In the early 1850s, the young Grant grappled with poverty and limited opportunities. It was during this time that he built Hardscrabble, a modest log cabin that stands as a symbol of his resilience and resourcefulness.

This article delves into Grant’s early life in St. Louis—and the story of Hardscrabble, which continued on after Grant’s death. From its origins as a frontier home to its transformation into a traveling historical oddity, the cabin reflects both the hardships of Grant’s early life and the evolving story of St. Louis.

Grant’s initial move to St. Louis

Born in Point Pleasant, Ohio, Ulysses S. Grant was assigned to Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis in 1843 after graduating from West Point. There, he served alongside his friend and classmate Frederick T. Dent, who introduced him to his family’s 850-acre plantation, White Haven, just a few miles away. Grant quickly developed a fondness for the estate, which became a favorite retreat during his time in St. Louis. He later recalled,

“As I found the family congenial, my visits became frequent. There were at home, besides the young men, two daughters, one a school miss of fifteen, the other a girl of eight or nine. There was still an older daughter of seventeen, who had been spending several years at a boarding-school in St. Louis, but who, though through with school, had not yet returned home. She was spending the winter in the city with connections, the family of Colonel John O’Fallon, well known in St. Louis. In February, she returned to her country home. After that I do not know but my visits became more frequent; they certainly did become more enjoyable.”

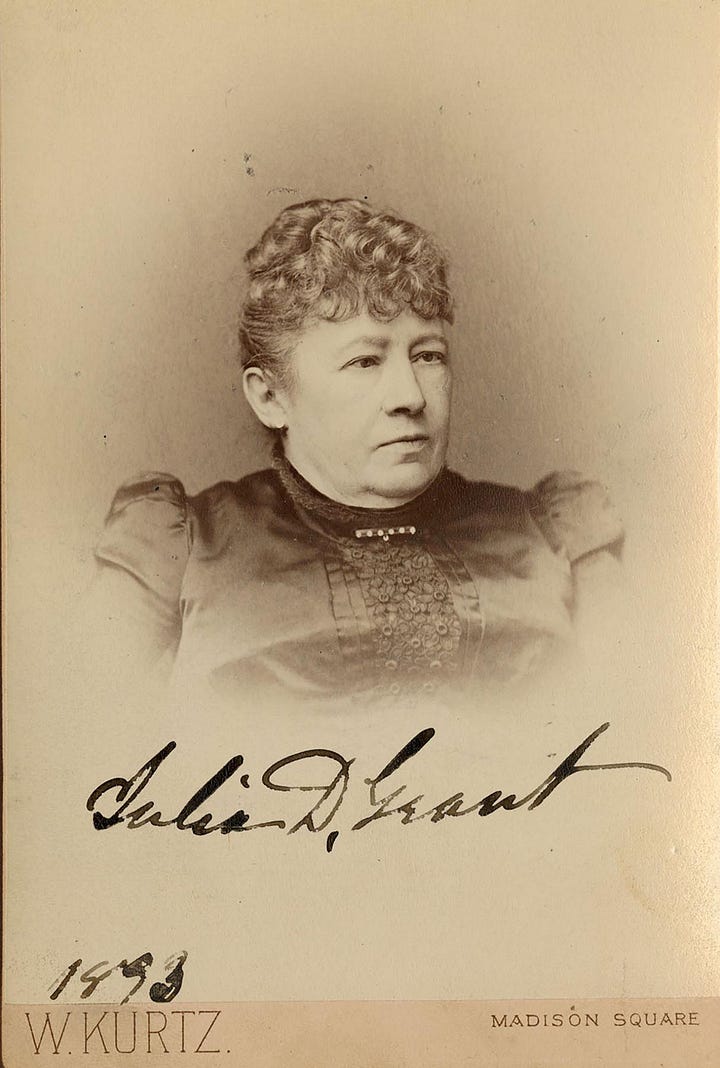

The daughter who captivated Grant’s attention was Julia Dent. During the spring of 1844, she and Grant grew closer, with him later reminiscing, “We would often take walks, or go on horseback to visit the neighbors, until I became quite well acquainted in that vicinity.”

Grant and Julia Dent’s engagement may have been a love match, but their families were far from thrilled. Julia’s parents doubted that Grant, with his modest income and uncertain future, could provide for their daughter. Meanwhile, Grant’s abolitionist parents took issue with the Dent family’s use of enslaved labor—a divide so deep that they refused to attend the wedding. Despite the family drama, Grant and Julia tied the knot on August 22, 1848, at White Haven, with the young officer fresh off his service in the Mexican-American War.

Early married life proved challenging for the Grants. Grant’s military career took him to far-flung postings, including New York, California, Vancouver, and Panama, while Julia, pregnant or caring for their growing family, frequently remained behind. The long separations took a toll on Grant, leaving him grappling with isolation, boredom, and mounting personal struggles. His Army pay couldn’t cover the cost of bringing his family out to the West Coast, prompting him to try his hand at various business ventures—all of which ended in failure. With finances stretched thin and rumors of heavy drinking sullying his reputation, Grant resigned from the Army in 1854, frustrated and unsure of what lay ahead.

How Hardscrabble came to be

Grant’s return to civilian life brought him back to Julia at White Haven. He took up farming on 80 acres that Julia’s parents had given Julia as a wedding present. Reflecting on this challenging chapter, Grant wrote in his memoirs, “I was now to commence, at the age of thirty-two, a new struggle for our support.”

Determined to succeed as an independent farmer, Grant threw himself into the work, cultivating wheat, potatoes, corn, and other crops. He also tended orchards and cleared trees from the property. As Grant recounted in his memoirs:

I worked very hard, never losing a day because of bad weather, and accomplished the object in a moderate way. If nothing else could be done, I would load a cord of wood on a wagon and take it to the city for sale.

His optimism about this new chapter was evident when he remarked to a friend,

“Whoever hears of me in ten years will hear of a well-to-do old Missouri farmer.”

Grant’s vision of independence also included building a home for his family. In the fall of 1855, he began cutting and hewing logs to construct a cabin on an elevated site near his crops, located along what is now Rock Hill Road at present-day St. Paul’s Churchyard. Julia organized a house-raising with neighbors and enslaved laborers, but otherwise, Grant completed much of the work himself, including cutting the logs, shingling the roof, laying floors, and building the stairs.

The modest cabin, which Julia nicknamed “Hardscrabble,” had four rooms—two upstairs and two downstairs—separated by hallways. Despite her husband’s efforts, Julia was unimpressed by the roughness of the log cabin, which she felt was beneath the standards of her upbringing. She later recalled in her memoirs,

[Ulysses] thought of a frame house, but my father most aggravatingly urged a log house, saying it would be warmer. So the great trees were felled and lay stripped of their boughs; then came the hewing which required much time and labor; then came the house-raising and a great luncheon. A neat frame house, I am sure, could have been put up in half the time and at less expense. We went to this house before it was finished and lived in it scarcely three months. It was so crude and so homely I did not like it at all, but I did not say so. I got out all my pretty covers, baskets, books, etc., and tried to make it look home-like and comfortable, but this was hard to do. The little house looked so unattractive that we facetiously decided to call it Hardscrabble

The family moved in during the fall of 1856, but their stay was short-lived. Just three months later, Julia’s mother passed away, and at Col. Dent’s request, the Grants returned to the main house at White Haven. Grant continued farming for another four years, managing not only his own land but also helping with the operations of the Dent family’s 850-acre plantation. Alongside enslaved workers, Grant felled trees, tended livestock, and completed numerous repairs and remodeling projects around the estate.

Despite his relentless effort, farming proved to be an uphill battle. While 1856 saw a successful harvest, the Panic of 1857 devastated crop prices, pushing the Grants deeper into financial hardship. To make ends meet, Grant even pawned his gold watch to buy Christmas gifts for his children. By 1859, a combination of mounting debts, persistent financial struggles, and a lengthy bout of malaria forced Grant to abandon farming altogether.

Selling off Hardscrabble—and getting it back

Grant’s farming ventures at White Haven had reached a breaking point. Unable to make the farm profitable and burdened by mounting debts, Grant and Julia sold Hardscrabble and its 80 acres to a German immigrant, Joseph W. White, for $7,200. Grant moved into the city of St. Louis, where he hoped to find more stable work, leaving his wife and children behind at White Haven. However, financial troubles and career instability continued to haunt him.

Desperate for an income, Grant partnered with Julia’s cousin, Harry Boggs, to form Grant & Boggs, a real estate and debt collection business, which opened on January 1, 1859. The work—grueling, tedious, and ill-suited to Grant’s disposition—provided little relief. During the week, Grant boarded with Boggs in the city, walking back to White Haven on weekends to visit Julia and their children. By spring, the family joined him in St. Louis, renting a modest home at 7th and Lynch in the Soulard neighborhood.

That August, Grant and Boggs brokered a complex transaction, exchanging the Hardscrabble farm for a house and two lots at 1008 Barton Street. White soon defaulted on his mortgage payments, leading to years of legal battles. Julia eventually reclaimed the property in 1863 after a Missouri Supreme Court ruling in her favor, but the ordeal only added to the Grants’ financial instability.

Amid these struggles, Grant was desperate to find work. He pursued a position as County Engineer in 1859, a role that would have paid $1,500 annually. Despite endorsements from two Democratic members of the County Court, his association with his father-in-law’s pro-slavery politics led the three Free Soil members to reject his candidacy. This disappointment dealt another blow to Grant’s fragile confidence, and by October, he resolved to leave St. Louis.

In 1860, the Grants moved to Galena, Illinois, where Grant accepted a stable position in his father’s leather goods business. Working alongside his brothers, he was finally able to provide for his family and pay off debts.

It’s worth pausing to reflect on the fact that Ulysses Grant was, up until this point, largely a failure. He had been broke when he left the Army. Despite a lot of hard work, he was a failure at farming. He then bounced from job to job. Many of us can likely relate to him at this point—he wasn’t heroic, successful, or someone to admire. He was just an average Joe, barely able to make ends meet. What was remarkable about him was his resiliency,

The Civil War's outbreak in April 1861 gave Grant a chance to return to military service and repair his reputation, but it came with challenges. Initially overlooked, he fought for recognition until Congressman Elihu B. Washburne secured him a commission. In June 1861, Grant was appointed colonel of the 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment, launching his rapid ascent to General of the Union Army.

Becoming the owner of White Haven

After the Civil War, and before he became president in 1869, Grant used funds earned from his military service to reassemble his wife’s family farm at White Haven, which had been divided among the Dent children earlier in the decade. By 1867, he had recovered his Hardscrabble land, and over the next several years (during his presidency), he expanded his holdings to over 1,000 acres by 1873. Although he envisioned White Haven as a thriving farm and retreat, he never returned to live there permanently, managing the estate remotely through letters to his resident managers.

Grant focused on raising cattle and horses, planting crops like oats, hay, and wheat, and maintaining orchards near White Haven and Hardscrabble. He also improved the property, adding barns and stables. Yet, the farm never turned a profit, and financial losses mounted. By 1875, strained finances and presidential obligations led Grant to explore leasing or selling the property. Despite his efforts, including offering the land at reduced prices with flexible terms, White Haven remained unsold.

Post-presidency in New York, Grant became entangled in financial ruin through his son Buck’s Wall Street firm, Grant & Ward. Unbeknownst to Grant, Buck’s partner Ferdinand Ward operated the firm as a Ponzi scheme and manipulated Grant’s reputation to attract investors. In May 1884, the scheme collapsed, leaving Grant bankrupt. Grant borrowed $150,000 from William Henry Vanderbilt to cover the firm’s debts. When the firm failed, Ward fled, leaving Grant unable to repay the loan. Determined to honor his debts, Grant and Julia had to give up nearly all of their assets, including White Haven, Hardscrabble, and all of the remaining 646 acres, which were signed over to Vanderbilt on April 15, 1885. Julia later recalled, “When I signed this last deed, it well-nigh broke my heart.”

Despite Vanderbilt’s willingness to forgive the debt, Grant insisted on repayment. Stricken by throat cancer and facing financial ruin, he began writing his memoirs to provide for his family. Encouraged by Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), who promised to secure at least $25,000 for the work, Grant completed his memoirs just one week before his death on July 23, 1885. Ironically, the published work was a financial success and provided for his family.

Hardscrabble on the move

In 1888, Vanderbilt’s agent Chauncey M. Depew sold White Haven to Luther H. Conn, a former Confederate captain turned wealthy St. Louis real estate magnate. Conn, drawn to the estate’s historical and sentimental value, renamed it “Grantwood” and sought to preserve its legacy. Conn’s efforts were well-received, with Julia Grant visiting the property in 1894 and expressing her appreciation for the preservation of the old Dent mansion and other landmarks.

In 1891, Conn sold Grant’s handbuilt Hardscrabble cabin to real estate developers Edward and Justin Joy for $5,000. The Joys dismantled the cabin and moved it to the Old Orchard neighborhood in Webster Groves just off Big Bend, where it was reassembled to serve as their real estate company and residence.

As Edward Joy recalled in a 1903 Post-Dispatch article,

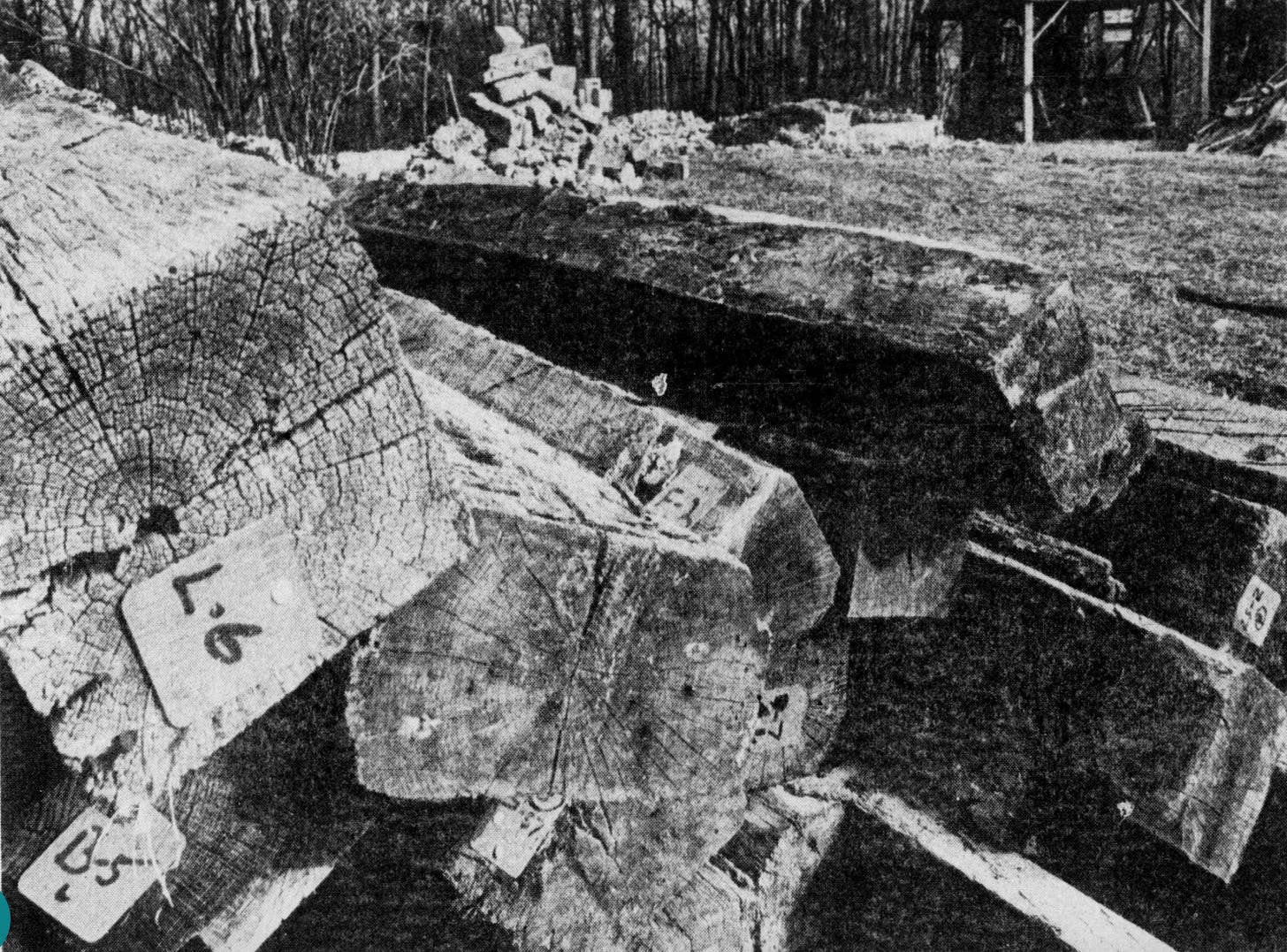

“I removed the cabin to a lot owned by me in Old Orchard, four miles from its original site, where it now stands. There was great danger of relic hunters destroying it had it been left on the farm…. It was necessary to tear the cabin down, but we marked every log, every plank and every brick with its proper number, so that the house was put together again just as it was before.“

In the same article, a woman then living in the cabin remarked,

“I’ve seen a good many log houses down in Kentucky, where the building of them is something of an art, and I must say that, in my opinion, Mr. Grant was a much greater warrior than he was an architect.”

Today, the short street that runs beside the Frisco Restaurant on Big Bend is named Log Cabin Lane in memory of the cabin.

It remained in this location until 1903.

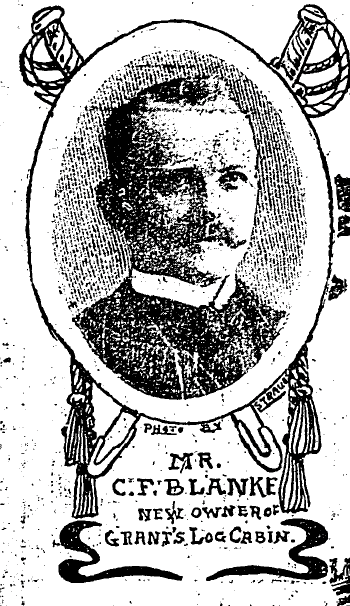

In 1903, Cyrus F. Blanke, a coffee salesman with an eye for marketing, purchased the cabin for $8,000. Determined to preserve the historic structure while promoting his business, Blanke once again dismantled Hardscrabble and relocated the cabin to Forest Park in preparation for the 1904 World’s Fair.

Reconstructed next to the Palace of Fine Arts (now today’s St. Louis Art Museum), the cabin became a centerpiece for Blanke’s coffee enterprise. Fairgoers flocked to the site, drawn by its association with the former president and Civil War hero, as well as by the coffee and tea sold on the premises.

Hardscrabble returns home

After the conclusion of the World’s Fair, something needed to be done with Grant’s cabin. Some proposed moving it from Forest Park to the Jamestown Exposition—a fair in 1907 celebrating the 300th anniversary of the Jamestown settlement—or possibly to Coney Island.

Judge Leo Rassleur, formerly of the Grand Army of the Republic, initiated a movement to prevent Grant's historic log cabin from being moved out of St. Louis. He promoted its possible preservation through a popular subscription campaign. Emphasizing the cabin’s historical significance, he stated:

“I am afraid that the historic cabin will never be returned to St. Louis if once it is shipped away, and I believe this is an opportunity for St. Louis to obtain a building of historic value. I believe we should buy it and preserve it to show our children the immense possibilities of this country.”

Blanke, the cabin’s owner, also wanted it to remain in the city. He turned down offers to sell it out of state and offered to sell it to St. Louis, but the city declined. To save the cabin, August Anheuser Busch Sr. purchased it in 1907 and relocated it to the former Dent plantation, which he had acquired in 1903 (and where he would build the Busch family mansion that stands to this day).

There, the cabin was reconstructed about a mile south of its original location in a spot that overlooks Gravois Road. (It’s worth noting that Busch did not acquire the land that included the Dent home at White Haven. Today that house, located directly across Grant Road from Grant’s Farm, is known as the Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site.)

The cabin became part of a larger legacy when Grant’s Farm was opened to the public in 1954 by August “Auggie” Busch Jr. Today, Grant’s Farm is a 281-acre wildlife preserve and family attraction featuring exotic animals, a tram ride through scenic landscapes, and historic landmarks.

In 1978, Hardscrabble was disassembled for restoration. Prochet Construction, which had experience with historic homes, cataloged all the pieces and replaced several rotten logs. After the restoration, the house was furnished with period items.

Today, while the cabin is not open for regular tours, visitors can glimpse the historic structure during the free tram ride through the park. For those interested in exploring it further, private tours offer a closer look at the cabin and its place in Grant’s story.

You can also visit the original location of Hardscrabble in St. Paul’s Churchyard just off Rock Hill Road.

Hardscrabble, a modest cabin born out of poverty and necessity, has endured the passage of time to become a tangible link to our nation’s history. Its continued presence serves as a powerful reminder not only of Ulysses S. Grant’s perseverance during challenging times but also of the twists and turns of our own city’s history.

As always, thanks for reading. Please consider sharing it with your friends.

And if you enjoyed my work on Unseen St. Louis, please consider a paid subscription if you have the means to do so. Your support helps make my efforts sustainable and keeps all of this content free for everyone.

Sources

“The Famous Grant Cabin Changes Hands,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 15, 1903

Ashton Farrell, Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site Video, July 2, 2020.

Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant

The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant (Julia Dent Grant (Author), John Y. Simon (Editor), 1988:

Grant’s Farm, Wikipedia.

Esley Hamilton, White Haven (Dent-Grant House, National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form, October 1985.

Hardscrabble: The House That Grant Built, Ulysses S Grant National Historic Site, National Park Service.

The History of Grant’s Farm, Grant’s Farm website.

Julia Grant, Wikipedia

Michael Korda, Ulysses S. Grant: The Unlikely Hero. 2004.

Becky McReynolds, “Grant’s Cabin Taken Apart for Restoration,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 12, 1978.

Mary-Lynn Pell, "Grant's Farm ." Clio: Your Guide to History, December 12, 2014.

Pharus-map World's Fair St. Louis, 1904. Library of Congress.

Nick Sacco, A Brief History of U.S. Grant’s Hardscrabble Log Cabin, Exploring the Past, November 27, 2015.

“To Hold Grant’s Log Cabin Here: Movement Started to Prevent the Historic House from leaving Forest Park, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 25, 1907.

Ulysses S. Grant. Wikipedia.

Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site, Wikipedia.

Ulysses S, Grant and Julia Dent Grant Exhibit, National Park Service.

“When Grant Was ‘Broke’," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 21, 1908.

Ralph Williams, “Grant’s Cabin Will Rise Again, Restored,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 28, 1978

I've visited Grant's Farm several times over the years both when I lived in St Louis and later during a visit, but I hadn't realized how nomadic a history the cabin has had. Thanks for the clarification as well regarding the difference between the farm and the National Historic site! Noted for my next visit to the city.

I echo the others- ty for boiling down this cool journey the cabin made! I had no idea!

Question- do we know where near St Pauls Churchyard Hardscrabble originally sat? Curious if there is anything there now to indicate its history…