Growing up in North St. Louis County in the 1970s, I didn’t have a firm grasp of the different townships that criss-cross the county. I knew I was from St. Louis but that my mailing address was Ferguson (yes, that Ferguson). I heard the names Cool Valley and Kinloch and Berkeley and University City and Clayton, but as a kid, everything blurred together and I had only the vaguest sense of socio-economic and racial disparity in housing and infrastructure.

As I explored last week, I grew up in the Wyndhurst apartment complex, just east of Lambert Field Airport, and immediately south of a creek that separated us from the city of Kinloch. In searching the history of the area, I discovered that directly north of my complex and across the creek, there was a barricade that prevented the Black residents of Kinloch from driving into Ferguson, which was then largely white. After protests in the late 1960s, the two cities worked to remove the barricade, only to have others demand the construction of fences and walls to keep the communities apart—much like the so-called peace walls built in the north of Ireland, or the Israeli West Bank barrier.

Until a few weeks ago I had never realized there was so much going on right next door. In the following piece I try to to peel back the history that led to the barricades and how it explains so much about the nature of North St. Louis County even today.

A brief history of Kinloch

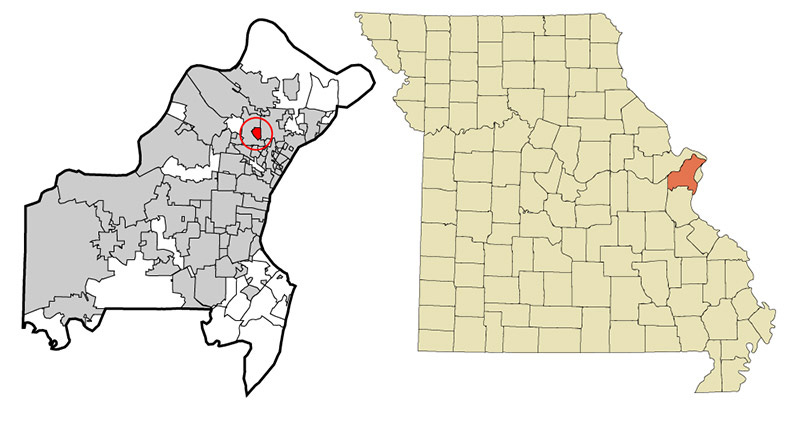

Kinloch, the first Black incorporated city in Missouri, is a tiny city of approximately one square mile wedged between Ferguson and Lambert-St. Louis International Airport.

In the late 19th century Kinloch sprung up along the Wabash Railroad. The first residents were white, but some land was set aside for Blacks, many of whom were former slaves who worked in the white households. In 1885 a real estate company sold lots in the area, advertising specifically to Black residents in St. Louis and elsewhere around the country.

Early on, Kinloch was generally regarded as a pleasant area. In 1898 the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described Kinloch Park as a “beautiful suburb” and noted, “no suburb around the city has a more attractive location or is growing more rapidly than this one.”

In 1912 President Teddy Roosevelt became the first president to fly at the airstrip at Kinloch Field, an early airport that later gave way Lambert Field, the region’s airport. Upon receiving his invitation, he said, “will visit the field, but under no circumstances will I make a flight.” When he arrived, he changed his mind.

With Black soldiers returning from WWI, and others fleeing racial violence in East St. Louis in 1917, the city grew rapidly in the first few decades of the 20th century. By 1920 the population of Kinloch was nearly 2000, and as people moved in, neighbors helped each other build homes, often from salvaged lumber. By 1940 the population was 3607, and by 1949, there was a population that hit 5100. Many residents worked in white homes or took jobs at the steel mills and automotive plants in the area. The little town didn’t have a lot of amenities, but it did have an elementary school, a few shops, churches, and at one point, even a movie theater.

William H. Gillespie, who documented much of the history of Kinloch, called the city “a very tight community with a family and religious orientation.”

The city was eventually incorporated in 1948.

The boundary wall

By the 1960s, Kinloch was home to over 6000 people, while neighboring Ferguson to the east and south was a much larger (and at the time, largely white) city of 28,000 residents. And despite sharing a sizeable border, only two streets connected the two towns—and one of them was intentionally unusable for decades.

Long-time Kinloch resident Larman Williams described how Kinloch was different from Ferguson from the beginning. As the LA Times recounted,

People were poor, sure, but they worked hard. The problem was that other than the airport, all the businesses — and so, the tax base — were based in Ferguson. Black people from Kinloch could cross into Ferguson during the day to work as maids or factory men. But they had to be back across the border by sunset, when the gates closed.

From the earliest days of Kinloch, a train and then a streetcar ran along Suburban Avenue through Ferguson and into Kinloch. The right-of-way was owned by the St. Louis Public Service Co. When the streetcars were discontinued, the company relinquished the land in 1948.

Although the road was used for traffic for a while, it wasn’t in good repair. Eventually, in the late 40s or early 50s Ferguson built steel barricades blocking off the street, which according to Ferguson Mayor John G. Brawley were considered “safety measures.”

While the barricade may not have been specifically constructed to keep people out (I was unable to find any documentation on this, but will continue to investigate), the lack of political will on Ferguson’s part to rehabilitate the road—and as we’ll see, ongoing resistance to having Suburban Ave. open to through traffic—certainly could be construed as such.

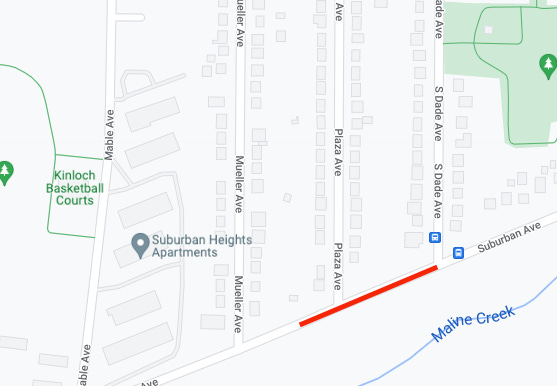

Here’s a quick and dirty map of the area (I lived where the SKF facility is now at the bottom of the map.)

In 2014 the LA Times toured the area with 80-year-old Ferguson resident Dorothy Kaiser. They traveled down Suburban on the Ferguson side, and as they approached the city border, she went silent. As the paper put it:

“I wouldn’t really know this area,” she says.

This is where the gate used to be, she says.

The one to keep black people out.

Filmmaker Jane Gillooly made a documentary entitled Where the Pavement Ends, which aired on PBS in 2020. She interviewed a number of people about the boundary wall. While everyone knew where it was, no one remembered what it looked like. Of course, when it was there, no one, on either side, ever had a reason to go there. It was just a double dead-end street to the residents of both communities. But everyone knew why it was there.

With the rise of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, people in Kinloch started pushing for it to be removed, and to make Suburban a thoroughfare through both communities, while many residents in Ferguson opposed it. After Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, some marchers made a point to breach the barricade in order to reach Zion Lutheran Church in Ferguson.

Removal and efforts to resurrect the wall

After months of arguments and protests, the Ferguson Ministerial Alliance presented a resolution to the Council stating, “Although we realize that the barricade on Suburban at the city limit was at first simply a safety factor,” they now believed that it “has become a symbol of racial separation.”

Finally, just a couple of days after the march in Kinloch, the Ferguson City Council voted to remove the barricade on Suburban on April 9, 1968.

At the time, Councilman Carl V. Kersting (put a pin in his name) said, “we’re not interested in keeping the barrier up because of racial feelings.” Instead, he argued, the people along the street “do not want the rumbling of trucks and cars in front of their homes.” He also noted that he would “hate to see this area opened up to aggravate a situation that is, at best, unpleasant.”

For Kersting, the barrier wasn’t about race at all. It was simply a safety thing, a convenience thing. It reduced traffic, that’s all. Right.

Build up that wall?

As it turned out, in the years after the barricade was removed, there were some Ferguson residents that didn’t like the new status quo. In 1975 some of them started a campaign ostensibly to make Ferguson safer.

And Councilman Kersting was back.

Along with the ‘Plaza Heights Improvement Organization’, Kersting demanded that the barricade be rebuilt. He also proposed that Ferguson purchase a 2-foot-wide, 2000-foot-long strip of land that behind people’s homes along the border, and called for a variance to build a 10-foot-high fence in the strip.

The fence would prevent burglaries, Kersting and the PHIO said. Kersting claimed once again that this had nothing to do with race because both Black and white families were crime victims.

And he was determined. He was quoted as saying, “if I had my way, I’d build a brick wall.”

Fortunately, not everyone in Ferguson agreed with Kersting. Ferguson city attorney Al E. Nick called him on it, saying, “that’s just what they did in Germany.”

One resident, Betty O’Keefe, pointed out that she had lived on the street adjacent to Kinloch for 20 years, and Kinloch hadn’t ever troubled her. It was only “in the last five, six years that things have started going bad.”

She didn’t draw a connection to the removal of the barricade, but it’s not hard to see the implications. In 1975 the barricades had only been down for a little ove six years. Some Ferguson residents blamed Kinloch’s Black population for all crime in Ferguson, and pointed to the road connecting the communities.

Ferguson resident James Quinn argued, “If these people want to build a wall over there, good for them.”

The fact was, the idea behind the fence was to prevent people from Kinloch from entering their city, and everyone knew it. And some were willing to say as much. Ferguson resident Tom Ryan pointed out that “there was enough racism without the fence,” while Ferguson’s city attorney Nick pointed out: “A burglar isn’t going to be stopped by a fence.”

Meanwhile, Kinloch’s city attorney, Harold L. Whitfield, wasn’t having it. He pointed out, “if there are some problems [with Kinloch residents],” why wouldn’t the city want to co-operate with Kinloch officials?”

In January 1976, undeterred from previous failures to create his racist wall, Councilman Kersting once again popped up calling for a fence. In this latest effort, he demanded a chain link fence be constructed immediately—guess where? If you said across Suburban Ave., you’d be mostly right.

Kersting actually wanted to fence off the entire block of Suburban from the Kinloch border to Dade Ave, as I’ve illustrated above. “We should pass a motion to install a fence tonight and have it up this weekend,” he said. “Then we could study other proposals as we go along.” Mayor Charles H. Grimm was not impressed, however, and the motion failed.

In the end, the fence and barricade contingent lost their war, and Suburban remains open to this day.

Kinloch and Ferguson today

The city of Kinloch first got on the map due to its airstrip. Ironically, it was the development and then the expansion of Lambert Field that helped usher in Kinloch’s downfall. But since the 1970s, Kinloch's story has been one of depopulation, fraud, and greed by people within and outside the city who think they can make a quick buck on the city’s ongoing misfortunes.

About Kinloch, the Post-Dispatch noted in 1978 that

“no major roads run through the city. No industry has ever located there, despite its proximity to Interstate Highway 70 and Lambert Field. Its isolation from the rest of St. Louis County, both physically and racially, has plagued Kinloch since its founding.”

In the 1980s, the airport began buying homes for a noise-abatement program, purchasing over 1000 properties. The city’s population plummeted, and poverty and blight took hold. Then in 1995, the airport planned to buy out most of Kinloch for expansion, though nothing ever came of those plans, and St. Louis, who owns the property, recently turned a bunch of it over to NorthPoint development.

In 1990 the population was 2702, with 17 white residents, with more than half of the households receiving public support of some kind. The mayor at the time, Bernard Turner Sr., and many residents were convinced that the airport wanted to wipe Kinloch off the map.

Today there are roughly 250 people clinging to life in a city that refuses to disincorporate but has almost no housing or businesses and is largely filled with empty lots, deteriorating buildings, and huge piles of trash from people outside the community using Kinoch as an illegal dumping ground. Just to the west is a PepsiCo distributor, and towards the airport are other warehouses, all part of the new NorthPoint development. Meanwhile, Lambert Airport, which is owned by the city of St. Louis, still owns half of the parcels in Kinloch, while St. Louis County owns Kinloch Park and a few other properties. And most of this land is vacant, drawing no revenue for the city and offering no opportunities to attract new residents.

In 2000, the Riverfront Times wrote an article about Kinloch. They pointed out that

“Kinloch's very survival depends on redevelopment of the land taken by St. Louis. That was something Kinloch and St. Louis recognized in the early 1980s, when the buyout began, but that is no longer the case.”

In the end, what made Kinloch possible has also led to its demise. As former Mayor Joseph L. Wells explained in 1978,

“segregation in itself is the reason for Kinloch being here, and segregation is the reason the city was cut off…. No one wants to annex the poor in the first place, and when they’re poor and black, you can forget it.”

Note: There’s a new documentary, The Kinloch Doc, made by filmmaker Alana Marie. I was unable to find a way to view it for this article, but I hope to see it in the future.

Trailer:

I hope you enjoyed this article. For more articles like this, be sure to subscribe, and I would love it if you would share it with others who might be interested.

If you would like to leave a comment (especially if you’re from the area or have more information or corrections to share!) I would love to hear from you.

Both towns, Kenlock and Berkeley are now giant shit holes

As Lambert took over Kinloch and more air traffic caused constant noise, many residents moved to Berkeley contributing to decline in Kinloch's population. Unfortunately, I understand about 75% of Berkeley is owned by landlords living out of the area and not maintaining their properties. It's a sad site to see.

The author mentioned living in the Wyndhurst Apartments. I lived on Brotherton Lane that went past that development. Wyndhurst slowly deteriorated and required a police substation to maintain the peace. Several times a day, the police would fly by my house with lights and sirens going to get there before the substation opened. Finally, all the apartments were torn down and the land became part of the industrial park.