St. Louis's amazing technicolor floodwalls

How Paint Louis got its start—and a brief look at this year's mural artists

Welcome to Unseen St. Louis, where I share the history of lesser-known parts of the city’s history. Today, let’s look at the connection between the Mississippi River and urban art.

I’m also excited to introduce a new component of Unseen St. Louis, so be sure to read to the end!

Where pragmatism and creativity collide

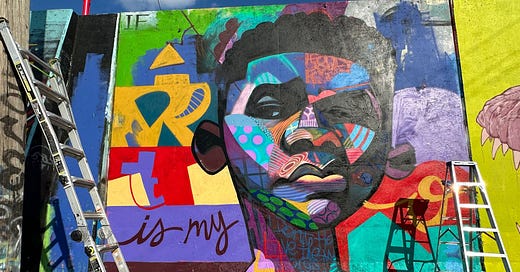

On Saturday, I checked out Paint Louis, the annual Labor Day weekend festival at the Mural Mile/Graffiti Wall along Wharf St. in Downtown St. Louis.

It totally blew me away! I’ve been down to the Graffiti Wall before, but seeing all the artists hard at work in the hot sun was pretty powerful. Plus, the vibe down there was excellent, with all the visitors, food and beverage trucks, vendors, and music. In short, it was a lot of fun.

And as always, I had to ask… how did all of this come into being?

The ‘Project’

Before we can talk about Paint Louis and the murals, we have to start with the “canvases”—the thick slabs of concrete on which the murals get painted and refreshed every year.

From the founding of St. Louis, the Mississippi River was both the city’s greatest asset and its largest foe. In good times, the river allowed the city to grow and prosper thanks to the trade the river made possible. However, when it flooded, it could (and often was) devastating, with businesses, farms, and homes inundated by the river. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many lives were lost to flooding in the city.

By the 1950s, the city of St. Louis finally decided to do something permanent to protect downtown against the unpredictable surges of the Mississippi River. In 1947 and 1951, the river reached a flood stage of over 40 feet, and the city was finally ready to do something about the problem. After much political wrangling, the city secured funding from the federal government to take on a massive flood control project. On February 24, 1959, dignitaries, public members, and key figures in the project gathered for a monumental $130 million initiative to shield St. Louis from flooding.

The plan—soon to be known as the Project—was to construct 11 miles of walls and levees, along with 27 pumping stations and updated sewers. The barriers themselves—concrete and earthen levees—would run from Maline Creek at Riverview Drive down to Chippewa. The goal was to build a system that could withstand a flood of up to 52 feet, which was the height of the Mississippi when it flooded in 1844.

Below is a diagram of the planned flood protection system.

When the system was completed in 1965, river freight traffic increased substantially, and new trucking depots were built along Hall Street in north St. Louis, further expanding the city's economic power.

Ironically, in the 1960s, as the Army Corps of Engineers was building the flood protection system, people complained that the flood walls were too high. It took a while, but the naysayers were eventually proven wrong.

In 1993, the Mississippi River swelled to a staggering 49.6 feet at St. Louis, the highest in recorded history. According to the National Weather Service, water flowed past the Arch and downtown at a rate of 1.08 million cubic feet per second. The water came within two feet of cresting the floodwall, which held and saved the city from devastation.

Below is a photo of the river just below the floodwall during the 1993 flood.

The Mural Mile & Paint Louis

Nestled between Victor and Chouteau Avenues, south of the Gateway Arch, lies a stretch of the flood wall known as the Mural Mile.

Every Labor Day weekend since 1997, an event called Paint Louis welcomes hundreds of graffiti and mural artists worldwide. Their mission? To transform this two-mile stretch of the flood wall into a new and unique collection of art.

John Harrington, co-founder and organizer of Paint Louis, reminisced last year about the St. Louis alternative/hip-hop scene of the late '80s and early '90s that led to this artistic event.

Back then, the flood wall was a gathering spot where DJs, rappers, and breakdancers would jam while graffiti artists painted murals into the wee hours. These gatherings provided a haven for artists and performers, free from police interference or gang-related threats. As Harrington recalled,

“The jams kept getting bigger and bigger every year, and finally, since it got so big, we were like, ‘We should name it. Since it’s based off of the wall and how we value watching the artists paint, we called it Paint Louis.”

From the start, Paint Louis was a hit. Each year, artists from all around the world set up shop on a section of the wall and the area’s residents cheered them on.

For Harrington, Paint Louis was always more than just an event or a party. Recently, he commented on how growing up as a Black man in St. Louis presented its own set of challenges.

“The cops kept kicking us out of all the hangout areas like the Delmar Loop, the West End, Laclede’s Landing, so it was only place we could go where there were no people, no cops, nobody to bother us.”

Paint Louis became a means for him to give back, creating a sanctuary for the community to engage in artistic endeavors and show off an underappreciated art form.

However, because of its location on city property, Paint Louis has had its fair share of challenges. In August 1999, after only two years, Mayor Harmon pulled the plug on the event, claiming that the year before, the artists and attendees created many problems for the city.

Responding to that decision through a Post-Dispatch Letter to the Editor, organizers Joseph MacDonald and John Harrington pleaded their case on Sept 1, 1999:

“Paint Louis is designed to be a declaration of artistic proficiency and innovation. It can and (if allowed) will be both an attraction to the culture we passionately embrace and a landmark in our city for a younger generation.”

After a public outcry, the mayor eventually changed his mind and allowed Paint Louis to proceed—as long as participants agreed to some basic rules.

As Harrington recalled,

“Back in the day, some of the mayors liked it, and some of them didn’t. It’s still the last outlaw element of hip-hop; everyone knows a DJ, everyone knows a rapper, everybody dances like a b-boy, but not a lot of people do graffiti art or know about graffiti art.”

While the event has grown in popularity, the essence of “Paint Louis” remains the same. With the City of St. Louis' blessing, the event has grown to attract over 400 mural artists annually, who breathe life into the flood wall with their vibrant creations. As time passes, these artworks undergo further paint-overs, giving the original pieces new identities and layers of meaning.

Today, graffiti art has transformed the once desolate flood wall strip. As Harrington noted, “that area is still a like a no man’s land, but now it’s known for Paint Louis.” The Mural Mile has become a landmark for families, tourists, and wedding photoshoots. And the artwork serves as an ongoing testament to the transformative power of art and community and the dream of a more inclusive and vibrant St. Louis.

If you want to view the Mural Mile for yourself, it’s open 24/7, so head down Chouteau Avenue towards the river and then hang a right when the road ends. From there, you can drive or park and walk down the nearly two-mile stretch of murals, all freshly re-painted last weekend.

NEW! Unseen STL History Adventures

You can only appreciate history so much from a website or a history talk. To that end, I’m excited to announce Unseen STL History Adventures. Let’s get together and hit the road, checking out historical sites while meeting fellow history geeks!

Unseen STL History Adventures won’t provide traditional tours, but instead, we’ll have “go at your own pace” activities paired with social activities (think lunch or coffee) before or after the event.

Some of the Unseen STL History Adventures will piggyback onto existing events. For example, our first outing this Saturday will be joining the Pulitzer Arts Foundation’s curated tour of the National Building Arts Center’s new exhibit. But other events will be much more off the beaten path. Let’s visit historic bridges, talk about the coal and clay industries, and check out sites involved in the Manhattan Project here in St. Louis. We’ll even take a trip to the Mural Mile!

As much as possible, these adventures will also be accessible, so if you have mobility challenges, you can still join in the fun.

This will be a blast, so I hope you’ll join us! Sign up on Meetup.com at https://www.meetup.com/unseen-stl-history-adventures/

Thanks as always for reading. Be sure to mark your calendar for the next Unseen STL History Talks on Sept. 21st, when we will welcome Michael Allen and Emery Cox from the National Building Arts Center. Stay tuned for a special announcement post with more details in the next few days.

And if you haven’t already, be sure to subscribe to Unseen St. Louis so you don’t miss out on everything we have coming up.

Sources:

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 25, 1959; February 15, 1968; September 1, 1999

THE MURAL MILE (FLOODWALL) (Regional Arts Commission of St. Louis)

Paint Louis celebrates 25 years of art and hip hop at the flood wall (St. Louis Magazine)

Paint Louis Returns For 26th Year Colorizing St. Louis Floodwall (Forbes)

First, I want to thank Kathryn Vercillo of @createmefree here on Substack. Her weekly roundup led me here.

St Louis and the Metro area are my “other” hometown. The decade we lived there was transformative for me is a zillion ways, and I miss it so much. Finding this blog is a gift!

Jackie Dana loves St.Louis. I'm feeling the same when I reading her newsletter.