In this week’s Unseen St. Louis, let’s get down and dirty and explore a time when caves and beer went hand in hand. I’d like to offer a special thanks to local cave/brewery history enthusiast Mike DeBroeck who provided several of the images and some of the details in this piece. Any errors, though, are all mine!

Today Downtown St. Louis looks much the same as any other mid-sized city’s central business district. There are office buildings and hotels, restaurants and apartment buildings, and of course the Gateway Arch and a number of city parks. What you may not realize is that underneath much of downtown is a network of caves and tunnels that are mostly hidden away today but once were essential to the city’s industry.

Let’s dig into the history of the caves and the role they played in the growth of St. Louis breweries (and the Civil War!) for over 75 years.

The surprise sinkhole

History is often more interesting when it intersects with the present, and that’s exactly what happened back in March 2022, when a 50-foot-deep sinkhole suddenly appeared in Memorial Park, across from the Post Office at 18th and Market Streets.

Initially, reporters wondered where the tunnel went, and residents expressed concern. But thanks to the Metropolitan Sewer District, the cause was uncovered: a storm sewer line had been placed above an old tunnel used by the Winkelmeyer Brewing Company, and the older tunnel had collapsed, causing the sinkhole. To fix it, a plumbing company used heavy equipment to place nine large sandbags down in the hole, like the ones used for a levee, and then poured a bunch of concrete on top. An inelegant but hopefully effective solution to the hole.

Surprisingly, this wasn’t the first time a sinkhole suddenly appeared in the area. In 1959 there was a cave-in in Memorial Plaza that had to be filled with 4000 cubic yards of fill, and in 1960 the sidewalk sunk in front of the post office. Below is the 1959 cave-in.

But contrary to what reporters might say, these cave-ins aren’t random or mysterious. They’re actually a big part of St. Louis history.

The city built on swiss cheese

St. Louis was built on top of a series of cave networks. In the 19th century, numerous breweries sprang up on top of all of the local caves. Some had names largely lost to time—Lemp, Falstaff, Winkelmeyer—while one, Anheuser-Busch, is known to all.

If we go way back, the land where St. Louis is now was once covered by a vast sea. The deaths of millions of tiny creatures formed layers of limestone; this rock in turn was slowly carved out by streams, forming caves.

In the 19th century, many of these caves were utilized by breweries. As Joe Light, president of the Meramec Valley Grotto cave explorer group described it,

“A bunch of thirsty Germans show up, and the only way they can get their beer is to go underground, and they grab and utilize every cave they can find.”

Notable caves & the breweries that used them

The first breweries in St. Louis started around 1810, and by 1860 there were 40 of them. As we will see, many of them brewed lager beer and chose to locate their breweries over natural caves that maintained constant cool temperatures year-round. Before refrigeration, brewers could lager beer by bringing in blocks of ice in the winter to drop the temperatures for the brewing and conditioning process. For the rest of the year, the cool underground spaces also provided a good place to store beer away from the heat of a muggy St. Louis summer.

In most cases, the breweries modified the caves. The owners leveled floors, put in stairs and walls, constructed brick or stone vaulting (which both reinforced the cellars and helped draw away water seeping through the ceiling), and sometimes even installed narrow-gauge railroad tracks. Some cleared out all of the natural cave features, while others worked around them. Once the caves were ready, the breweries installed giant vats and other equipment for the brewing or storage of their products.

Here are just a few of the better-known caves and breweries in the area.

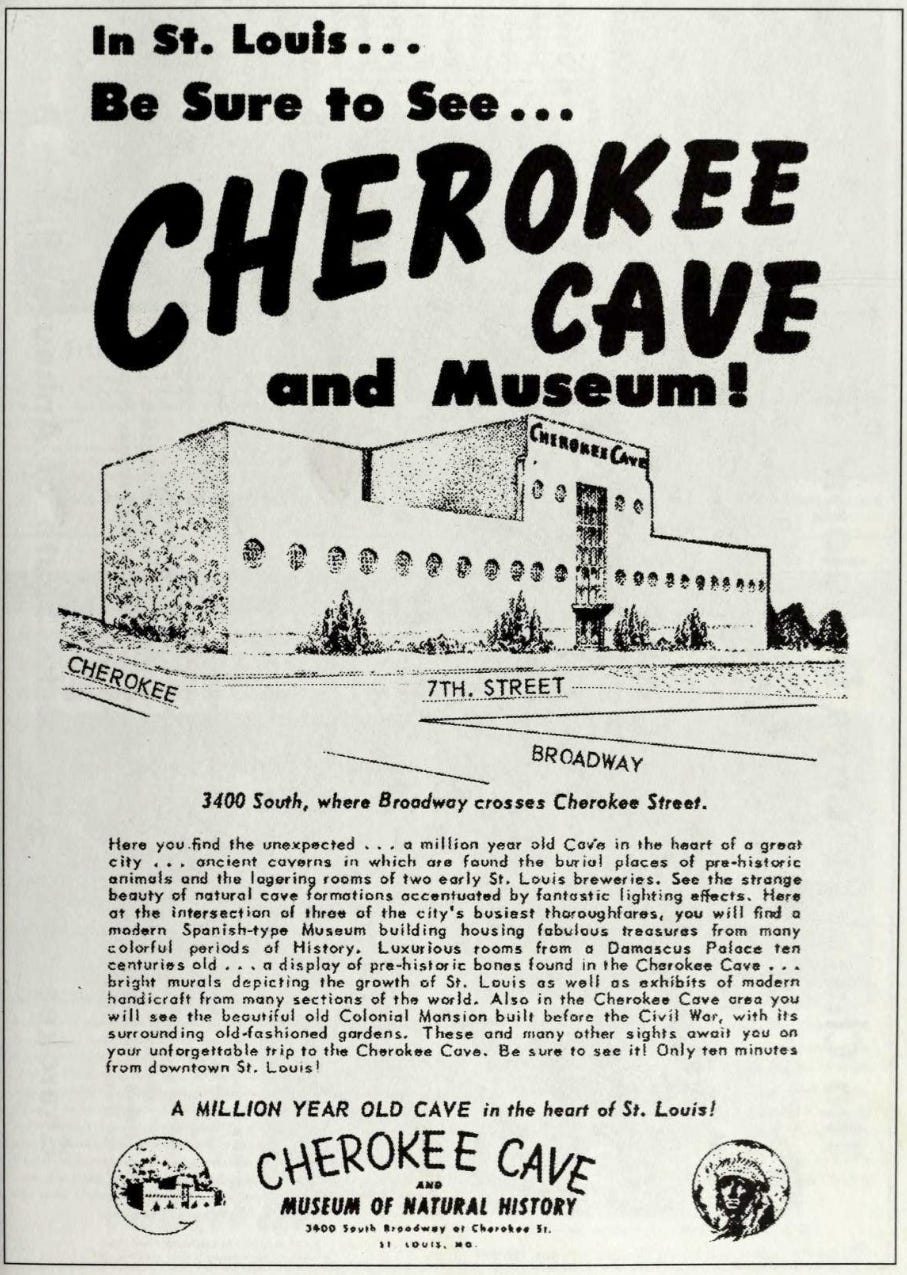

Cherokee Cave and Lemp Brewing

(between Cherokee, DeMenil Place, Utah, I-55, and S. Broadway)

The relatively large cave known today as Cherokee Cave first gained importance when Adam Lemp founded his brewery in 1840 and used the caves underneath his new brewery for beer storage and lagering.

Lemp was the first to brew lager beer in St. Louis. He had built a small brewery on 2nd St. but in 1850 relocated his brewery to the triangle formed by Cherokee and S. Broadway to take advantage of the cave underneath for his lagering cellars. By 1879 Lemp’s brewery (known as the Western Brewery until formally changed to Lemp in 1892) produced 88,000 barrels of beer annually.

During the Lemp ownership, not only was the cave used for brewing purposes. Because of the natural air-conditioning, part of the cave was turned into a theater, complete with clouds painted on the ceiling. The Lemp family also built a swimming pool.

Unfortunately, despite being a huge industrial presence in the city, Lemp closed its doors in 1921, selling their popular Falstaff brand to the then-named Griesedieck Beverage Company, which renamed itself Falstaff. (As an aside, the Falstaff Brewery in St. Louis was the #3 brewery in the country in the 1960s, but legal trouble and then acquisition drove the brand into the ground, and the beer was discontinued in 2005.)

The Lemps weren’t the only ones to use the cave. In 1856 Dr. Nicholas DeMenil bought the Chatillon mansion across the street from the Lemp brewery and used the cave underneath the house to store food; he leased part of the cave to the Lemps. Minnehaha Brewery also used the cave until the business went under in 1865.

After Lee Hess bought the DeMenil mansion and surrounding land in 1945, he developed Cherokee Cave into a short-lived local attraction. Among other things, he excavated a clay-filled passageway separating the Lemp and Minnehaha sections of the cave so that more of it could be viewed by tourists. As he did so, he uncovered the first of what would ultimately be 2000-3000 fossils from an extinct species of peccary (a type of wild pig) and a northern armadillo—these bones were excavated by specialists from the American Museum of History in New York.

The cave remained in operation until the Missouri Highway Department bought the land in 1961 for highway construction. Unfortunately, the cave entrance and some of the cave itself were destroyed with the construction of I-55 in 1964.

Since the closure of Cherokee Cave, there haven’t been many opportunities for people to visit the cave. A friend of mine told me that back in the 1990s there was a brief time when the Lemp Halloween attraction included a tour of the cave. She recalled there being an “old rickety iron cage kind of elevator” that descended into the cave, and as she put it, “It was TERRIFYING. I chickened out and went back and didn’t take the whole tour.” Apparently, others recall this Halloween attraction as well, but details are sketchy.

For a glimpse into Cherokee Cave in 1998, here’s an old video with Jim Kirchherr when he went underground. And for a nice updated history, check out Chris Naffziger’s article from 2017.

Cherokee Brewery

(Cherokee & Iowa)

Not to be confused with Cherokee cave, Cherokee Brewery opened in 1866 on Cherokee St. Like so many other breweries, it was constructed over a cave, which was heavily amended with quality masonry vaulting.

This brewery was reopened in recent years as Earthbound Brewery. They offer tours of the groin-vaulted beer cellars on weekends for $10 or $15 respectively depending on whether or not you’d like to sample a glass of their beer afterward. For more discussion of the architecture of the beer cellar as well as photos from the renovations, check out St. Louis Magazine.

English Cave

(East of Benton Park between Arsenal and Wyoming)

English Cave is the second-largest of the known caves beneath St. Louis. Records suggest it is between 25 and 35 feet wide and 350 feet long.

From what I have found, and what others have shared, it appears Joseph Phillipson built St. Louis Brewery, an ale and porter brewery, over this cave. Elkanah English was also involved in the business, and at some point bought out Phillipson. Then, possibly in 1839 and maybe earlier, Isaac McHose joined the brewery. McHose sold his portion of the property to Ezra English in 1851 shortly before McHose’s death in 1852. [Edit: The history of the brewery and cave has become a bit murky, and I am currently sorting it out. Thanks to Laura E. Tague and Mike DeBroeck for providing more details.]

The brewery itself shut down in the 1840s due to the cholera epidemic, but the cave continued on as an underground beer garden where guests could drink and bowl, and go on hot-air balloon rides above ground. Later the cave was used to store beer and wine, and for a while, there was even a mushroom farm. At some point in the early 1900s, the city sealed up the cave.

Due to the fact that no one knows the location of the entrance to the cave, English Cave was almost lost to history, but cave buffs wouldn’t let that happen. After extensive research, a team led by Bill Kranz, project facilitator for the McHose and English Cave Recovery, decided to take action. In 2020, they drilled two holes in the community garden that went right into the ceiling of the cave. They then used LIDAR to confirm that the cave was beneath their feet and to identify some of the cave features. You can read more about their exploration here, and in a future post, I hope to explore the efforts to find English Cave in more detail.

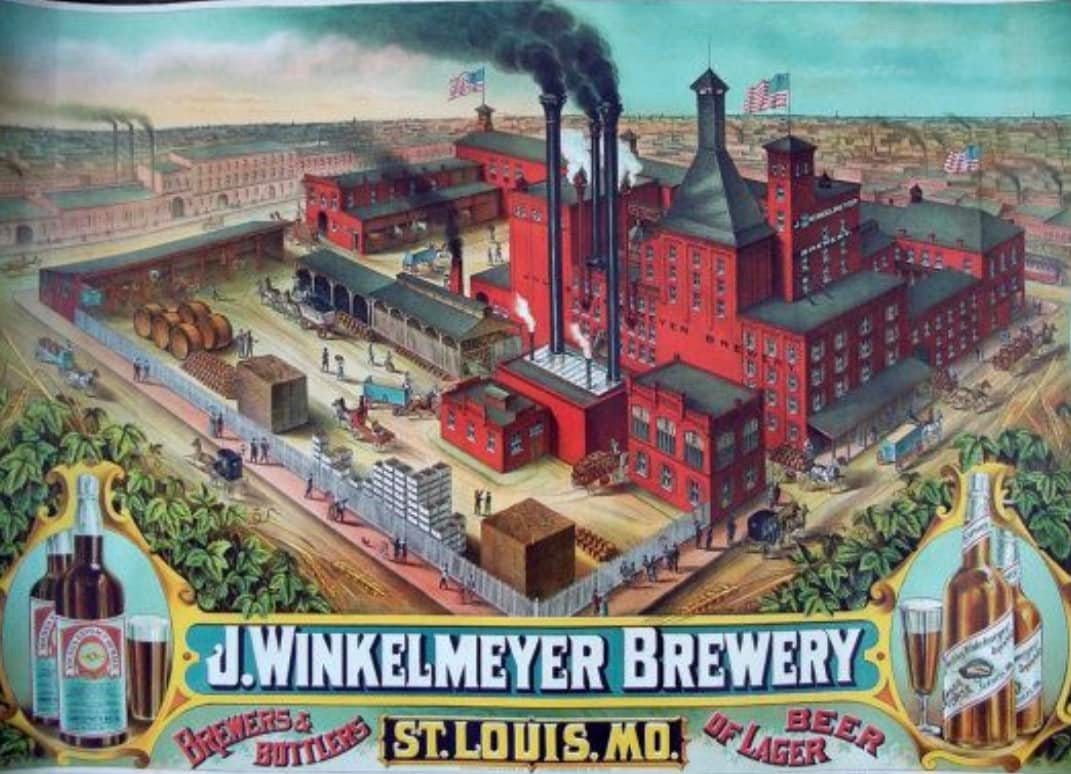

Winkelmeyer Brewing/Stifel Cave

(Market Street between 17th and 18th)

This cave is located beneath the Post Office at 17th and Market St. It was used by Julius Winkelmeyer and his brother-in-law Frederick Stifel when they started Winkelmeyer’s Brewing, located at 1714 Market Street, in 1843.

They chose a site for their brewery near the edge of Chouteau’s pond, a three-mile-long waterway that ultimately became polluted from both sewage and industrial waste and was drained in 1853. The location of the pond, south of where Union Station is now, was subsequently used as a railroad yard.

Winkelmeyer continued the brewery after the death of Stifel and Stifel’s wife during the cholera epidemic in the 1840s. When Julius died in 1867, his widow Christiana continued to run the business through its incorporation as Union Brewery, and until it was sold to the St. Louis Brewing Association in 1898.

Excelsior Brewery, run by the Winkelmeyers and Stifels, also operated on Market. Unlike most of its competitors, it continued until 1916, one of the last of the 19th-century breweries to close. In 1902 Christopher Stifel added ‘tombstone’ memorials to the cave under Excelsior Brewing, commemorating Julius Winkelmeyer and Frederick Stifel, and in the 1930s during excavation workers found the memorials still on the wall in the tunnels under the ground.

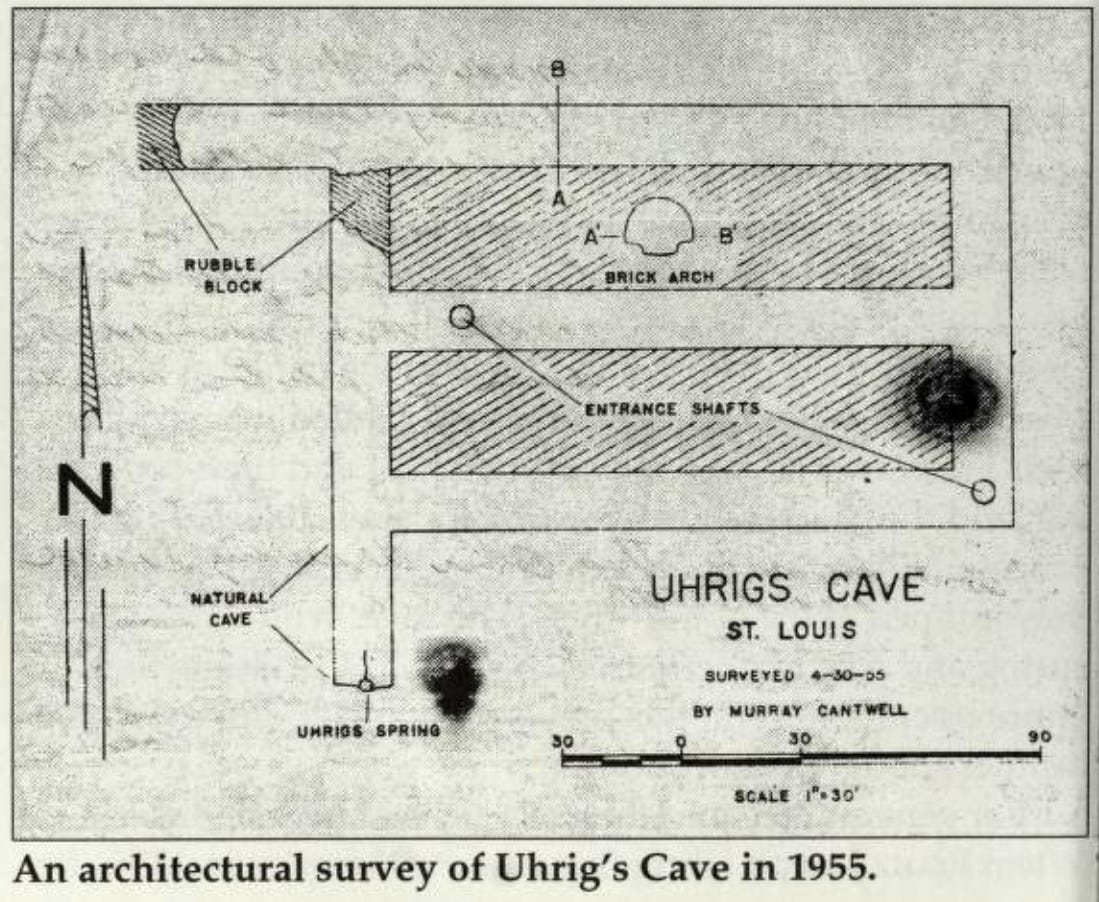

Uhrig’s Cave

(Jefferson and Washington)

In 1847 the Uhrig brothers started a brewery at 1804 Market St. near the present-day location of Union Station. Originally called Camp Springs Brewery, their operation had three cellars, two storage cellars, and a big malting cellar, along with a cooling plant. But they also purchased land from Dr. William Beaumont a short distance away at what is now Jefferson and Washington. The site was chosen in part because of the higher elevation, making it less likely to flood, as well as because the land was inexpensive. Despite there being no houses in the area at the time, the Uhrigs thought it would be good for a beer garden (if one can imagine it, that area was once covered with oaks).

Originally Urhig’s northern cave was about 40 feet long, but the Uhrigs blasted out tunnels and built a sizeable complex underground, expanding it to about 210 feet, with brick walls and arched ceilings. They connected this cave to the brewery on Market and installed a narrow-gauge railroad to move the beer from the brewery to the new lagering rooms.

In 1952 they started hosting various entertainment in the cave, and during the Civil War, the Home Guard used some of the larger tunnels for drills.

The brewery continued until 1874, but the cave lived on as a beer garden above ground, and a theater, swimming pool, roller rink, and bowling alley. Under the ownership of Thomas McNeary in 1884, a stage was built and McNeary and his brother installed electric lights and seating in the cave, turning it into a vaudeville establishment.

In 1908 the auditorium known as the St. Louis Coliseum was built over the cave, and it continued until Kiel Auditorium brought it to an end. For a while after that, the Coliseum was used as storage—until finally succumbing to the wrecking ball in 1953.

Schnaider’s Cave

(Chouteau Ave.)

Schnaider’s Cave is located at Chouteau and 18th St. under what was once the Schnaider’s Centennial Malthouse. In 1865 Joseph Schnaider built his brewery over another cave, using it for lagering and storage. Today, in the basement of the 21st Street Brewer’s Bar is the Malthouse Cellar, where you can still see the remains of underground tunnels that led beneath Chouteau extending south to the Schneider Brewery.

Anheuser-Busch Cave

(S. Broadway and Arsenal)

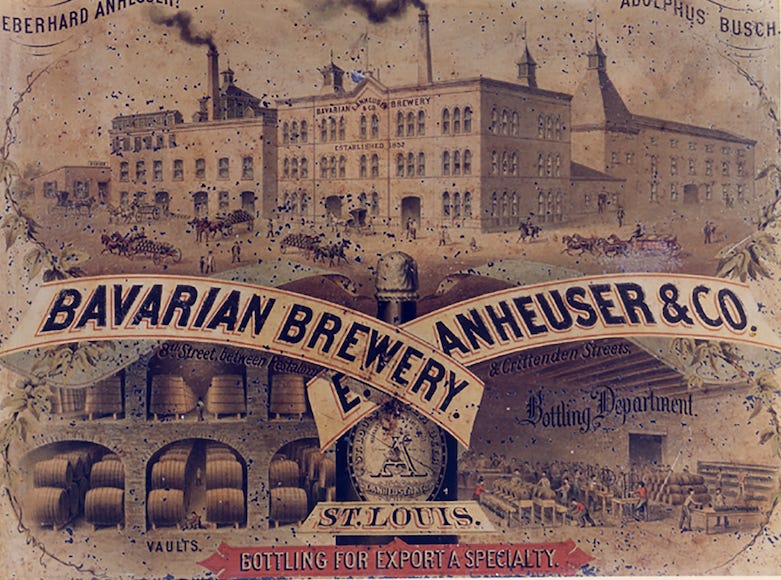

Yes, even our famous St. Louis brewery was built over a cave. The cave was initially discovered by George Schneider, who built the Bavarian Brewery there in 1852. Around 1859, Eberhard Anheuser, a local soap manufacturer, provided a loan to expand the brewery. When Schneider couldn’t repay the loan, Anheuser acquired the business and renamed it E. Anheuser & Co.

A couple of years later Lilly Anheuser, Eberhard’s daughter, married Adolphus Busch, the owner of a brewery supply company, while Lilly’s sister Anna married Adolphus’s brother Ulrich, forever bringing the two families together (and making for a very messy family tree!). After serving in the Union Army in the Civil War, Adolphus Busch joined the business. He became president when Eberhard died in 1880, and renamed the brewery the Anheuser-Busch Brewing Association.

Just like the other brewery caves, A-B used the caves under the brewery for lagering and storage. Because of the brewery’s proximity to the arsenal, during the Civil War, the caves and tunnels were used to relocate and hide arms and ammunition to prevent them from being taken during an expected raid.

What happened after the breweries closed?

Due to economics, competition, acquisition by British-owned St. Louis Brewing Association (a worthy subject of a future article!), and eventually, Prohibition, most of the 19th-century breweries closed between 1890 and 1920. Anheuser-Busch and Falstaff were the notable exceptions.

And with a rapidly growing city, few of the brewery buildings survived. In particular, when Union Station was built in 1894, all of the breweries along Market St. were already gone, and the caves were out of sight, out of mind.

When the breweries were demolished, some of the tunnels were repurposed as steam tunnels or for other underground utilities, but for many of them, workers typically dumped the materials into the caves underneath. This process didn’t necessarily fill up the cave, but it would block the entrances/access points.

And although most of the caves were forgotten, every so often they turn up again. When Market St. was widened in the 1930s, and again when the Post Office was built, workers stumbled across the remains of the brewing caves, discovering masonry walls, stone, and brick columns, and various brewing equipment. And of course, there are the occasional sinkholes like the one last month.

But if you’re interested in the caves, the ones at Earthbound Brewery and the Malthouse Cellar are still partially accessible.

Don’t look up—look down!

I hope this brief tour has intrigued you and made you see St. Louis in a whole new light. Breweries were an important part of the growth of St. Louis, and they might never have been as numerous or as successful without the caves underground.

If you’re curious to learn more, check out the numerous blogs, books, and other materials linked below.

thanks, i really liked the cave info. Great job.

I didn't realize urban caves were another thing StL and KC had in common. Including actual caves and mined-out spaces, a crazy 10 percent of the KC metro's industrial space is underground. One facility, Subtropolis, is supposedly big enough to hold 42 Arrowhead stadiums. But I prefer the St. Louis concept of building breweries over the caves better than what KC has done—almost all the underground spaces here are just warehouses and offices. 🍻