Welcome to Unseen St. Louis, where I write about the lesser-known history of the St. Louis area. I’ve been busy running the monthly Unseen STL History talks as well as trying to finish a novel, so I haven’t had a lot of time to write standalone articles, but I’m trying to get back into the swing of things, so to speak. I hope you enjoy this one!

Lone Elk Park, a St. Louis County Park of nearly 500 acres located in Valley Park in St. Louis County, is a testament to history's ability to blend natural beauty and wartime necessity. After a recent visit where I learned a little of its history, I wanted to learn more and share it here, along with some of my photos.

Minerals and mining

The sprawling area enclosed by the Meramec River and Interstate 44, the land where Lone Elk Park now stands, as well as the World Bird Sanctuary, Washington University’s Tyson Research Center, and the Endangered Wolf Center, was once known as the Tyson Valley.

Prior to the 1940s, this region was primarily exploited for its mining potential. The area’s rich chert deposits made it a favorite for native peoples, who used this material to craft arrow and spear points and as a trade good.

With the arrival of European settlers in the 1800s, chert deposits were less important than the limestone in the area, which was mined here. From 1877 to 1927, limestone was an important stone for building construction and railways, and lime was used for tanning, fertilizer, paint, and plaster. (Rockwoods Reservation is a park built in an area that used to have lime kilns).

The two major landholders in the area were the Rankens and the Minckes. The abundance of limestone led to the establishment of the town of Mincke, which even got its own railway line. However, by 1927, the limestone mine was exhausted, and save for some planned lumber operations, the area remained largely undeveloped for the first half of the century.

The Tyson Valley Powder Farm

In 1941, the US government, prepping to enter World War II, identified Tyson Valley, with its minimal development, as an ideal location for an ammunition dump and artillery range. The US Army amassed a 2,600-acre tract using eminent domain to create the Tyson Valley Powder Farm for storing and testing ammunition. The military created a fortified camp with 52 concrete igloo storage bunkers, 21 miles of roads, stables, fences, and more. These bunkers stored explosive materials, and notably, the area was used to store refined uranium developed by Mallinckrodt as part of the Manhattan Project (yes, although it was never mentioned in the Oppenheimer film, a lot of that uranium for the atomic bombs came from St. Louis) between 1942 to 1947. Soldiers in military jeeps and on mules patrolled the parameter keeping intruders out.

Between the wars

At the end of World War II, the government’s need for the ammo dump also came to an end. St. Louis County purchased the land in 1947. By July 1948, Tyson Valley Park was officially inaugurated, drawing numerous visitors. The park's attractions ranged from a mini-railway to a wildlife refuge, with hiking trails and horseback riding. Animals like elk from Yellowstone, buffalo from Oklahoma, and deer from Grant's Farm were introduced, offering visitors a unique wildlife experience.

The leftover structures from the war era found new life as restaurants and storage shelters. Some of the igloos were leased to mushroom farmers, providing the perfect environment for cultivation. Quickly the park became a popular destination, and the imported animals thrived. However, the peaceful reclamation was short-lived, as global politics shifted the park’s destiny once again.

The Korean War brought an end to the park

In 1951 as tensions in Korea escalated, the US government invoked provisions from its original land purchase and reclaimed the park, reinstating the Tyson Valley Powder Farm. Initially, they sought to lease the area, but by 1954, they decided to purchase it outright, leaving just a small 240-acre section that would become the West Tyson County Park.

The reclamation wasn't smooth. Although the Army sold off the bison, they decided initially to leave the elk and deer to roam. Unfortunately, a bull elk during rutting season damaged one of the Army’s vehicles. Additionally, since there wasn’t sufficient vegetation for the growing herd (and the Army didn’t want to pay to feed them), the elk had become a problem. An officer decided it was no longer safe to allow the elk to roam and issued a directive to remove the animals from the property. From October 1958 to March 1959, soldiers hunted the elk until no more could be found and donated the meat to local food pantries.

A lone elk

Following the end of the Korean War, the land entered a transitional phase. Initially, the government used it for storage, housing surplus items. By 1961, however, the government deemed the Tyson Valley Powder Farm unnecessary and put the land up for sale.

St. Louis County wanted to reclaim as much of this territory as possible. At the same time, Washington University eyed a substantial portion of the land for its biological and medical research initiatives. The government ended up selling 2,000 acres to the university. Interestingly, the deal came with a stipulation: the university must conduct research on the premises for a span of twenty years. Meanwhile, the County procured an additional 465 acres, integrating it into the West Tyson County Park.

The County envisioned transforming the park into a haven for winter sports enthusiasts, complete with skiing, sledding, and other winter activities. During these initial stages of development, as work was underway on what would become the Tyson Research Center and the expanded Tyson Valley Park, a park worker made an unexpected discovery.

A large elk had concealed itself among the trees for six long years. It had evaded the soldiers hunting the other elk and survived on the remaining vegetation without being seen. Park staff believed the elk had been young, perhaps the size of the deer, when the others were killed, and so it escaped notice.

It doesn’t take a huge leap to guess how this lone elk would change the trajectory of the park’s future.

At the time, the construction of a chain-link fence meant to demarcate the boundary between the park and the Tyson Research Center was in progress. Wayne Kennedy, the park’s superintendent, recognized the elk’s significance. He instructed park supervisor Gene McGillis to leave a gap in the fence. With his animal tracking expertise, McGillis spread a truckload of sand near the fence gap and patiently waited. Once elk tracks appeared in the sand, indicating the animal's entrance into the park and no subsequent exit, he informed Kennedy and the park closed the gap in the fence.

While the County's initial plans leaned heavily towards winter recreational activities, the discovery of the elk changed everything. Plans for a winter resort park were scrapped in favor of restoring the natural elements of the park as a habitat for the elk.

Acknowledging its resilient inhabitant, the park also received a new name: Lone Elk Park.

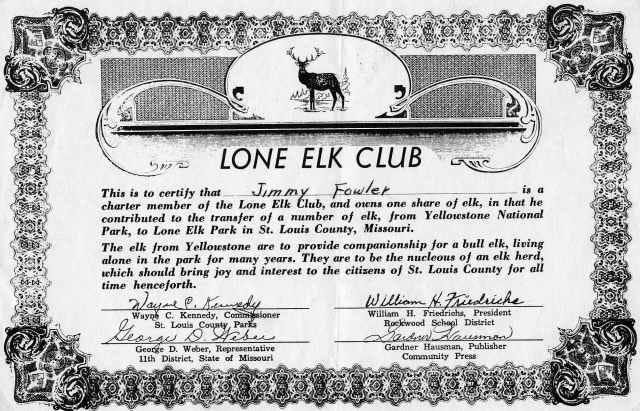

The local community, deeply moved by the elk's survival story, rallied around the park. Elementary students from the Rockwood School District raised $300 to help sponsor the transportation of additional elk from Yellowstone National Park. Those who contributed received a certificate, humorously termed "Elk Stock." Additionally, the Fred Weber Corporation generously funded the construction of a lake within the park with a $50,000 dam. Such was the elk's influence that none other than Walter Cronkite reported the unfolding events.

Upon the arrival of the new elk, the lone elk survivor must have been thrilled to have a new herd. Reports from the time indicated that merely 20 minutes after the release of the new elk, he joined the herd, remaining with them for a little over a year before he eventually died.

Besides the elk initiative, more buffalo were introduced from Oklahoma and the St. Louis Zoo, and for a brief period, the park even experimented with Barbados sheep.

Legacy

Today Lone Elk Park, a 546-acre county park, is a remarkable example of military and mining land reclamation. Its past stands as a reminder of how land can be repurposed, as well as the resilience of nature in the face of human intervention.

Today you can still see some artifacts from its time as a military base. Old bunkers, once part of ammunition storage, now serve as animal feeding zones. Vestiges of ancient mining activities, alongside remnants of old Army structures, such as the observation tower just inside the entrance, pepper the landscape.

When I recently visited the park for a special access tour at dawn (feeding time), I got to see all of the animals—the elk, deer, and bison—come out for breakfast. It was an amazing opportunity to get up close to these amazing animals (one of the bison was so close to me that I could have stuck my arm out of my car window and petted its head).

Before we started, our guide, Sgt. Cheryl Fechter of the St. Louis County Park Rangers, told us a little about the history I’ve shared above. She said they typically maintain 10-11 bison (with just one male bull at any time) and about 18 elk. The landscape is mostly oak and hickory trees that date back to the 1950s or later, as most of the land had been cleared when it was a military base. The animals help keep the understory clear of honeysuckle and other plants. A goal of the County Parks is to clear more of the land to make it more suitable for grazing, but that is resource-intensive and, therefore, on the back burner for now. She also let us in on a secret—the lake was built on top of sinkholes and has always leaked. When the water drains out, they try to trace it, assuming it flows into the Meramec River, but haven’t figured out where it goes. It is fed by a little spring and rainwater.

As we drove through the park, I spied a black cat on a fallen tree. When I asked the man feeding the animals about the cat, he told me that people sometimes dump pets in the park. Unlike other cats they have come across in the past, somehow, this one has evaded trapping for three years and lives alone on the land.

I’d like to think he is the reincarnated spirit of that lone elk that evaded hunting for so long—and changed the nature of this park forever.

You can visit Lone Elk Park (1 Lone Elk Park Rd, Valley Park, MO 63088) daily, 8 AM - dusk. It is free, but they do take donations inside the gate. It is known as a drive-thru park, and you never need to leave your vehicle to enjoy the animals. However, there are a few picnic facilities and a hiking trail among the elk (the bison are in a separate area). If you plan to hike, be sure to note that ticks are heavy, and you will need to take precautions.

I hope you enjoyed this brief visit to Lone Elk Park. None of this would be possible without the ongoing support of my readers. If you enjoy Unseen St. Louis, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

And I’d love it if you’d help me get the word out—share this article with your friends!

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lone_Elk_County_Park

https://patch.com/missouri/eureka-wildwood/bp--the-story-of-lone-elk-park

What a fascinating article! Thank you so much!

Love this! ❤️