From Ireland to St. Louis, with love

From mountain man to businessman, Robert Campbell's legacy lives on at the Campbell House

Happy St. Patrick’s Day! Here’s a special post to celebrate one of the earliest and most noteworthy Irish immigrants to St. Louis, Robert Campbell. And if you’re new to Unseen St. Louis, you’ll also want to check out last year’s post about the Kerry Patch, the large settlement of Irish in the city in the 19th century, and the kings, witches, and gangs that lived there.

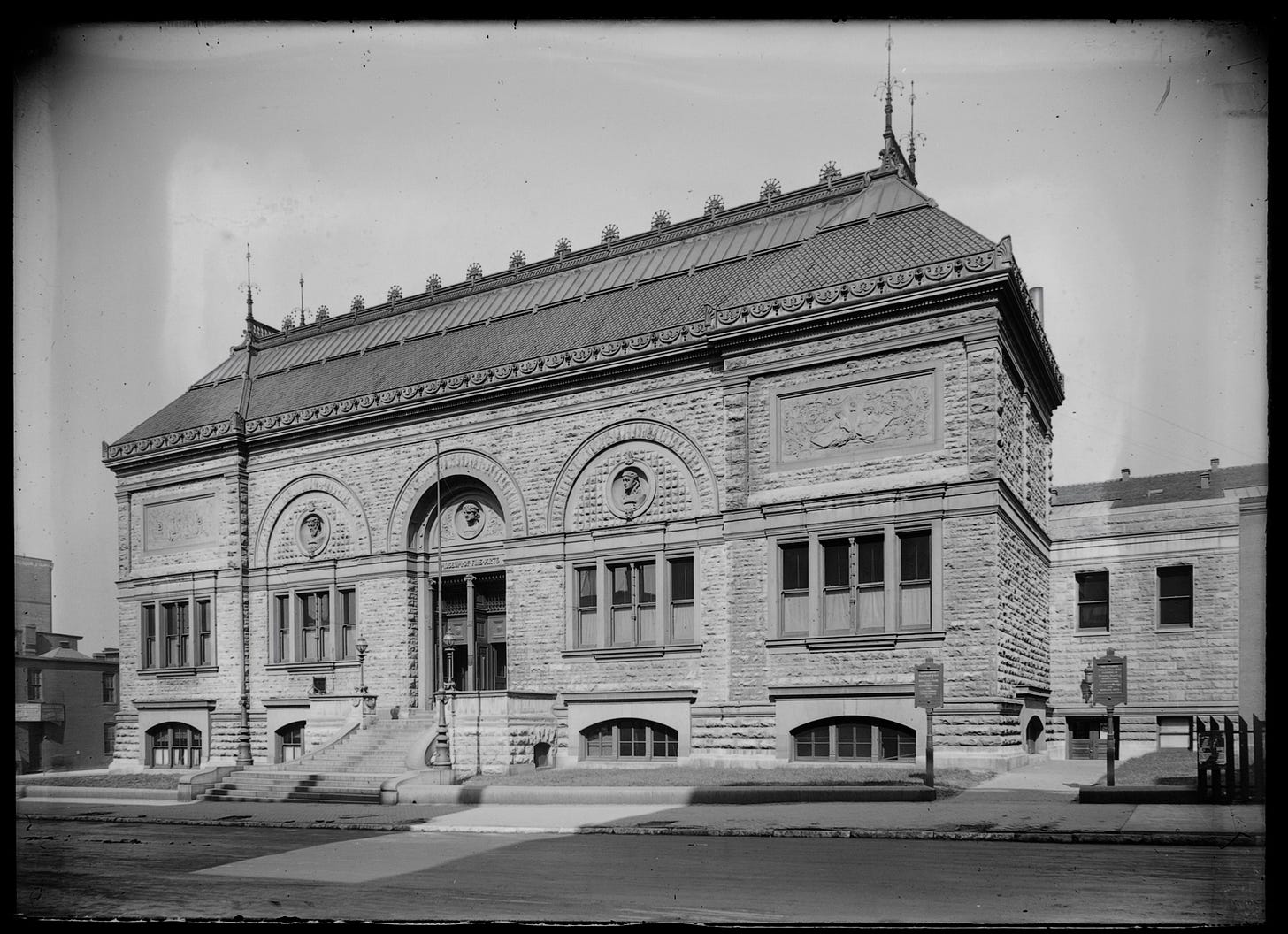

Last Sunday, I took a special tour of the Campbell House Museum in Downtown St. Louis. It’s located at 1508 Locust St., just two blocks from the St. Louis Central Library, and survives as a solitary white house amidst office buildings, parking lots, loft apartments, and other businesses.

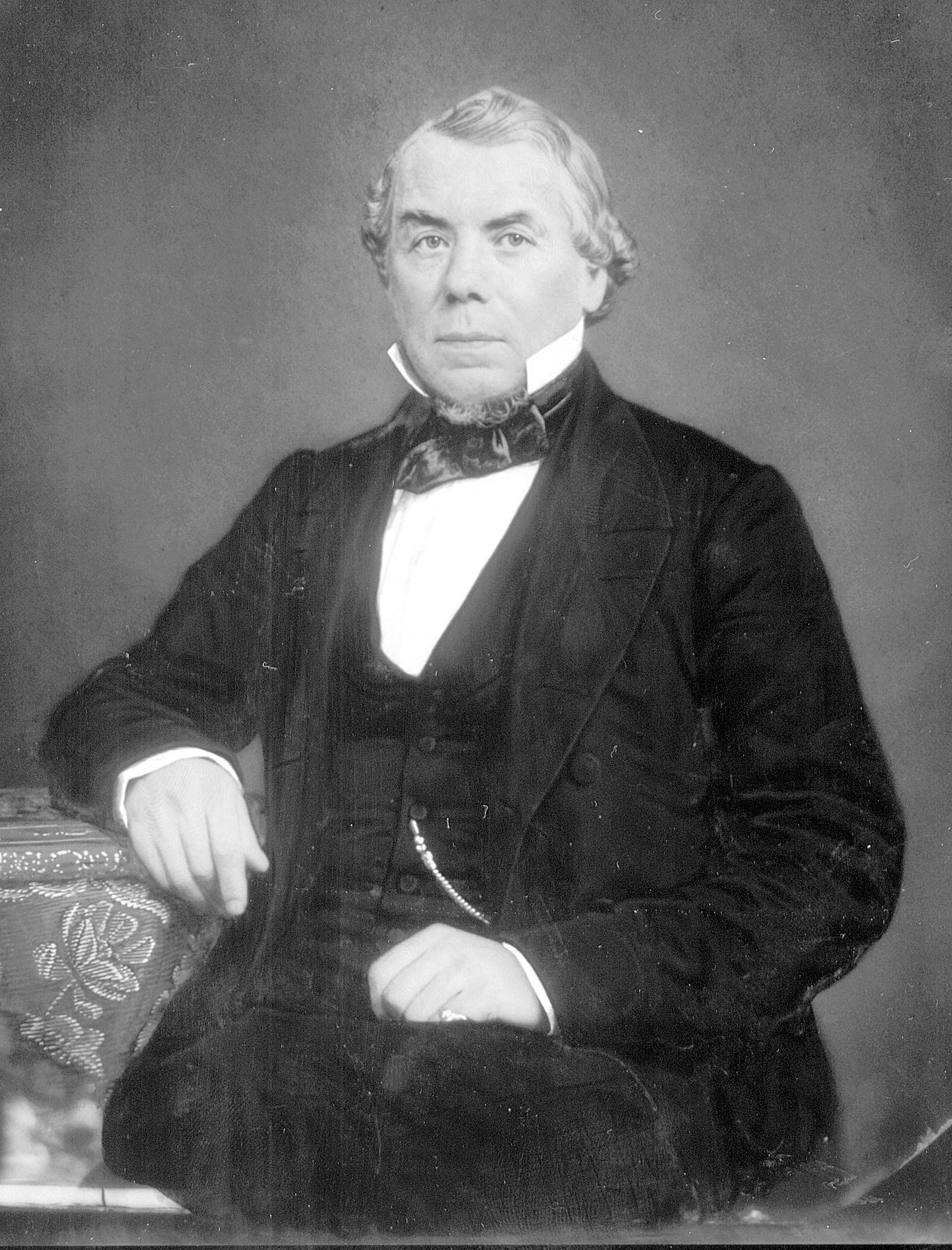

Robert Campbell of Ulster

Who was Robert Campbell?

In the mid-19th century, Robert Campbell was one of the richest men in St. Louis, and his home was located in one of the most desirable neighborhoods in the early city. But when Campbell moved here from County Tyrone in Northern Ireland, he wasn’t a wealthy man.

Born in 1804, he was the youngest son of his father’s second wife, and although the family was well off, his position in the family meant he would inherit nothing. With Ireland's economic troubles after the Battle of Waterloo, and no fortunes to be had at home, Campbell decided to try his luck in the New World.

Campbell arrived in Philadelphia in 1822, and there he met John O’Fallon of St. Louis, who hired him to work as a clerk in the frontier city.

However, Campbell had been sickly most of his life, and a doctor named Bernard Farrar told him,

"your symptoms are consumptive and I advise you to go to the Rocky Mountains. I have before sent two or three young men there in your condition, and they came back restored to health and healthy as bucks."

So young Campbell decided to move west and try his hand as one of the infamous Mountain Men.

Campbell and the Mountain Men

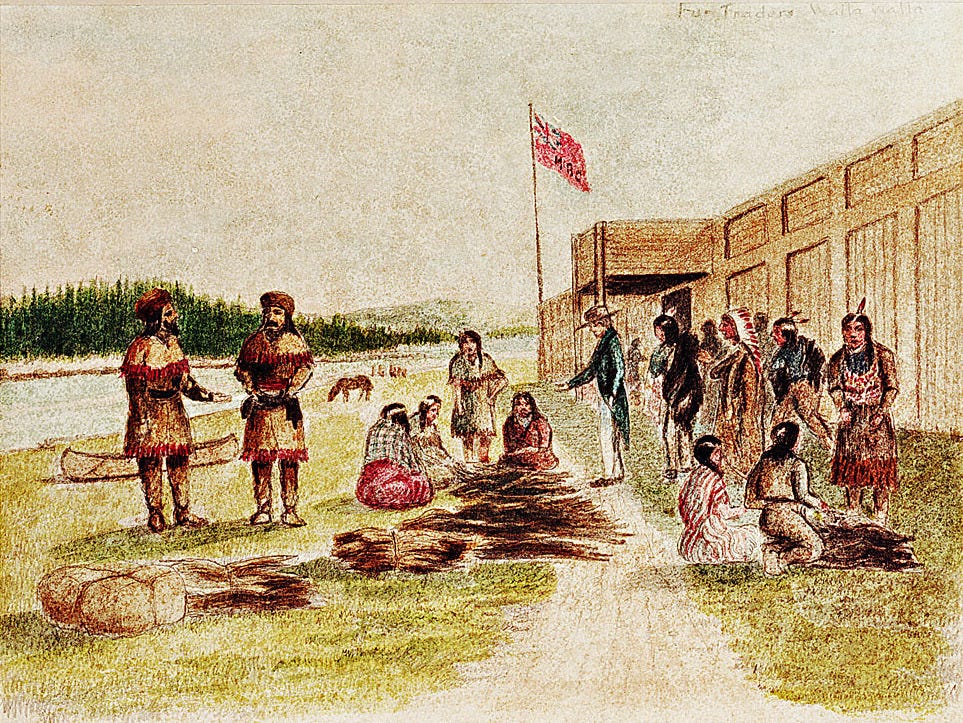

There’s a lot of lore about the Mountain Men, who included Kit Carson and Jim Bridger (the man who inspired the movie The Revenant), and in this quick piece, I won’t be able to do the history justice. For context, however, this was a group of men, mostly fur trappers and explorers, who roamed the lands of the Louisiana Purchase, particularly the Rocky Mountains and the western regions of the United States, from the early 1800s to the 1840s. They often worked for fur trading companies or as independent trappers, and although they sought many different animals for furs and skins, their primary target was beaver pelts, which were used to make fashionable men’s top hats.

Campbell departed St. Louis for the west with Jedediah S. Smith, in a company of 60 men, on November 1, 1825, and served as the clerk for the expedition.

Eventually, Campbell hooked up with David Edward Jackson and William Sublette (another man important in St. Louis history) and joined them as they "...hunted along the forks of the Missouri, following the Gallatin, and trapped along across the headwaters of the Columbia." In the fall of 1828, Campbell fell in with Jim Bridger in Wyoming. By the next spring, he had returned to St. Louis with a pile of the group’s beaver pelts, selling them for $22,476, a small fortune, with his cut being a hefty $3,016. This demonstrated to the young Campbell the fortunes to be made in trade.

By the early 1830s, the demand for beaver had diminished, and Campbell and Sublette focused on the buffalo robe trade and dry goods. Eventually, the two men became business partners in St. Louis and turned their profits to real estate, purchasing land in the upper Mississippi valley, and they also served as loan agents and investors.

Later in life, Campbell served on the board of the Missouri State Bank, and among other things, he helped secure funds for victims of the Irish famine.

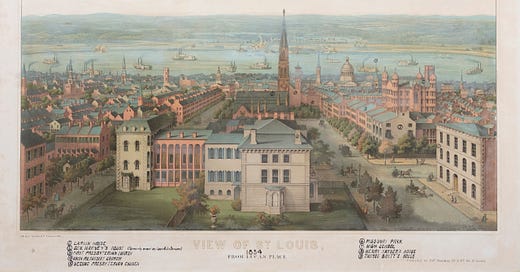

Lucas Place

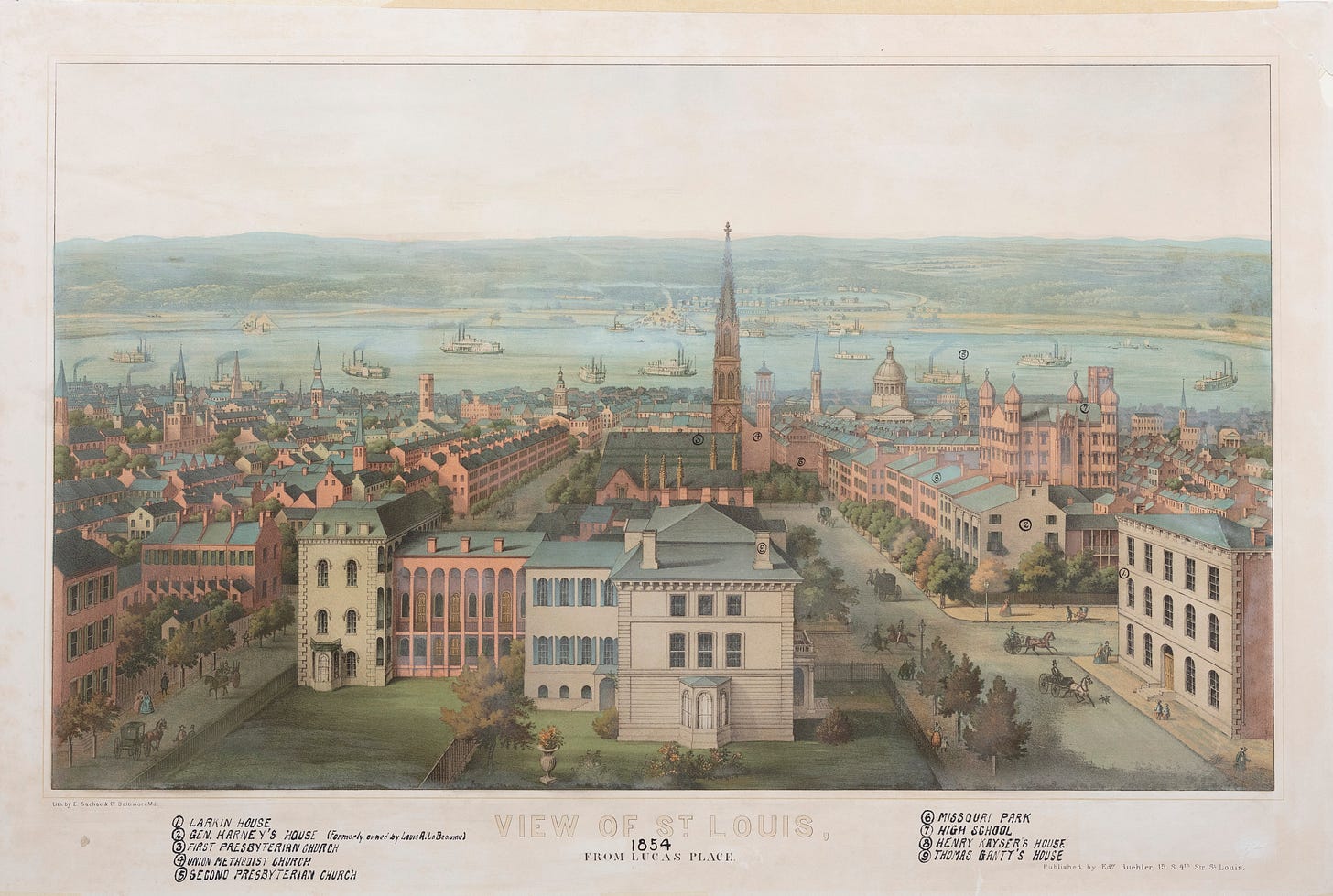

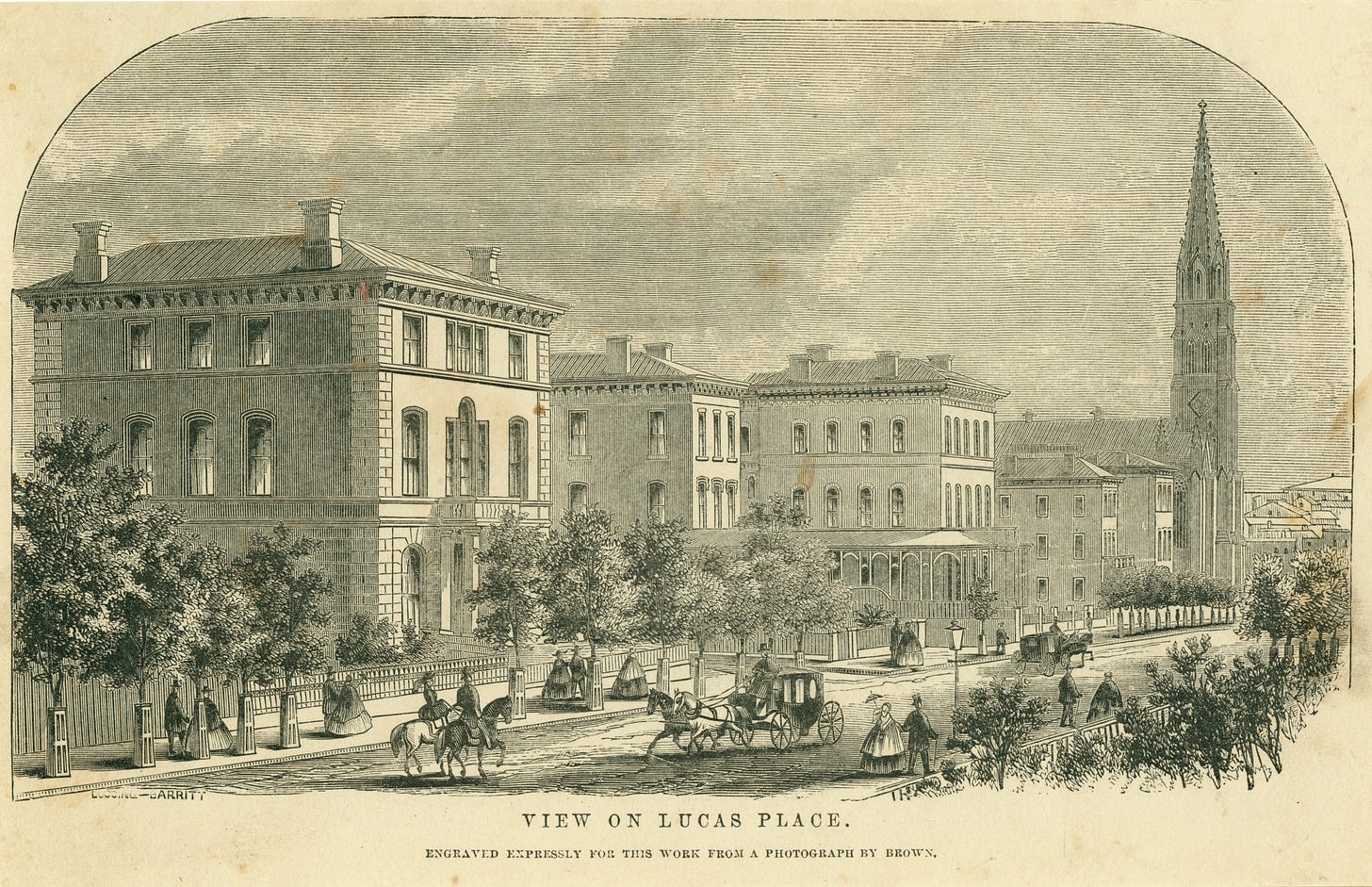

By 1851 Robert Campbell was a rich man. He had married Virginia Kyle, cousin to his brother Hugh’s wife, in 1841, and had lived first at the Planter’s House, a hotel near the riverfront, and then in rental homes. After losing children to the deadly cholera epidemic of 1849, the Campbells relocated to the fashionable Lucas Place, buying their home at 20 Lucas Place in 1854.

At its heyday, Lucas Place extended from 14th St. to 18th St. along what was Lucas and is now Locust. Below are a few historical images of the homes and other structures on Lucas Place (sadly, almost all of the buildings along Lucas Place are long gone.)

On a personal note, I was intrigued to learn that the first location of Mary Institute—my high school—was located across the street and down a few buildings from the Campbell home.

For a rough comparison, here’s a Google Street view of Lucas Place (now Locust St.) looking east from roughly 16th St. The Campbell House is the brick building on the right past all of the construction.

The Campbell family

At their home on Lucas Place, the Campbells believed their family would be safe from all of the diseases of the crowded riverfront neighborhoods. Tragically, even with this relocation, out of 13 children, only three survived to adulthood.

Robert in 1879, and his wife Virginia followed him in 1882. By the time of his death, Robert Campbell had amassed enough of a fortune to be considered one of the wealthiest men in Missouri, if not the entire country.

Their three sons continued living in the house until their deaths (the final son, Hazlett, died in 1938). They stayed well after the others in the neighborhood were turned into rooming houses and eventually torn down as the city expanded and the area around Lucas Place became the center of the garment and textile industry in the city. But it was because the children—none of whom married or had families of their own—remained in the house so long that the house survives to this day. It was the first house built on Lucas Place, and the last one to survive.

The Campbells are buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery.

The Campbell House today

According to our tour guide, Robert’s son Hugh had deeded the Campbell House to Yale University, but the educational institution didn’t have any use for an old house in St. Louis. The William Clark Society raised money to save the house, and Stix, Baer and Fuller (later Dillards) purchased the house from Yale University, turning it over to the City of St. Louis as the Campbell House Foundation.

It opened as the Campbell House Museum on February 6, 1943. According to Wikipedia, it was designated a City of St. Louis Landmark in 1946, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977, and became a National Trust for Historic Preservation Save America's Treasures project in 2000.

Our guide explained that a group called the Colonial Dames was the first to “renovate” it, painting the woodwork and removing much of the Victorian decor. However, later preservation and restoration efforts continued through the 1970s-1990s.

Beginning in 2000, the house was renovated again, starting with a process to stabilize the walls, some of which were starting to buckle. Much of the interior was restored to its original appearance thanks to photos Robert’s son Hugh had taken back in the day. Many of the items in the house today were owned by the Campbells. Many had been sold by the sons at auction, but the Foundation was able to purchase back some items while others were donated back to the house by later owners.

Beginning in 2019 and running through the lockdown of 2020-21, an expansion was built onto the back of the house, adding an elevator, gift shop, and classroom/video spaces.

The Campbell House interior

Here are a few images from inside the house.

The following image is maybe my favorite. It shows the extent of the soot from coal smoke that once covered the walls. You can see the outline of the armoire that stood against the wall, collecting soot particles over many years. The guides told us that the old adage that you’re not supposed to wear white after Labor Day and before Memorial Day came from the practice of burning coal for heat—in the winters, the soot would have destroyed people’s crisp white linen shirts, blouses, and other clothing. But out in the country during the summer, the wealthy could escape the smog of coal fires and wear white to their heart’s content.

Interested in learning more?

To learn more about the Campbell House Museum, you can visit the museum website for house and tour information and more history about the house itself, the Campbell family, the restoration process, and Lucas Place. You can even view an album of Hugh Campbell’s 1885 photos.

I hope you enjoyed this brief look into the life and home of one of the early families of St. Louis. I’d love it if you’d share it with your friends, and if you’re new here, please consider subscribing to Unseen St. Louis. Your support helps me continue to bring you articles about St. Louis history as well as our monthly Unseen STL History talks that take place on the third Thursday of every month. (And if you missed our talks last night, I’ll be posting a recap in a few days.)

I definitely need to visit! Thank-you!