Recently I attended a SeeSTL tour called “Beyond the Grave.” The tour, led by Amanda Clark, Community Tours Manager for the Missouri Historical Society, explored the city’s history of moving cemeteries, the practice of body snatching, and much more. (For more about Amanda and tour options through November, check out my recent article: Going 'beyond the grave' in St. Louis.)

This article explores an unexpected tidbit I discovered while on the tour.

It always pays to ask about the old books.

On the ‘Beyond the Grave’ tour, we visited the Hillcrest Abbey Crematory on Sublette Avenue. Manager and caretaker Steve DuLany told us how cremations were rare in the 19th century, and before this crematory was built in 1877 as the first of its kind west of the Mississippi, a body would have to be sent to the East Coast for cremation.

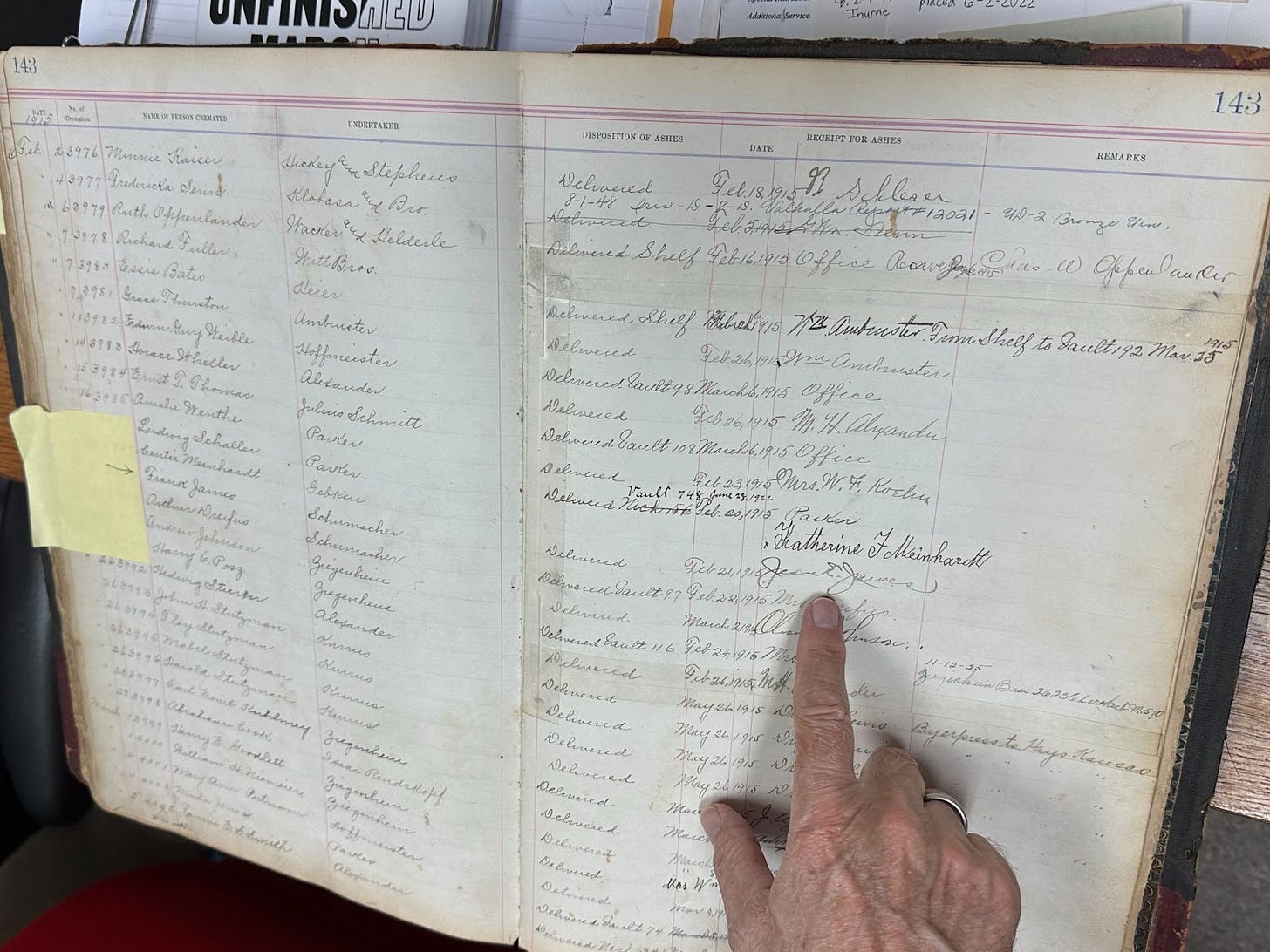

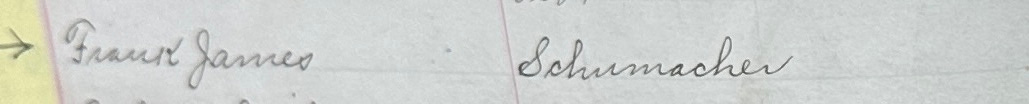

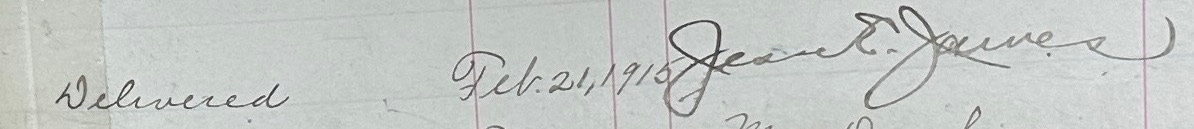

One of the tour attendees asked about the old books on the shelves behind his desk. DuLany explained that they were the original handwritten records of all the cremations that had taken place in the facility. Someone asked if anyone famous had been cremated, and like a magician pulling a rabbit out of his hat, he opened the book to a page conveniently marked with a sticky note.

And presto! In 1915 Frank James was cremated there, and his remains were picked up by the son of Jesse James.

Having heard all that, I had QUESTIONS. Why was Frank James cremated in St. Louis? Did it have anything to do with how his mother had feared people would dig up his brother’s grave (something I had seen in passing on Facebook)? I had to find out.

And that’s how I embarked on a fascinating journey into the lives and, more importantly, the deaths, of two legendary Missouri outlaws.

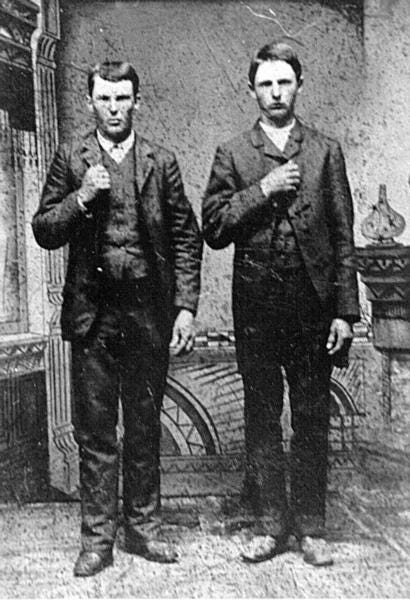

Jesse and Frank James

Outlaws Frank (born 1843) and Jesse (born 1847) James were two of three surviving children (they also had a sister, Susan) born to Robert and Zerelda James in Kearney MO, a small town northeast of Kansas City. Their father was a minister, slave-owner, and tobacco farmer who ran away to join the California Gold Rush in 1850 (and promptly died there, likely of cholera). Unable to support her three children plus six slaves, Zerelda—by all acounts, a strong and forceful woman who dominated everyone in her sphere—married wealthy neighbor Benjamin Simms in 1852, but they separated after a year. She married country doctor Reuben Samuel in 1855, and they continued on as slave-owning farmers until the outbreak of the Civil War.

During the Civil War, both Jesse and Frank James, living in an area of Missouri known as “little Dixie,” were loyal to the Confederacy, fighting as "bushwhackers" in Missouri and Kansas. After the war, the brothers continued their violent ways as outlaws, robbing stagecoaches, banks, and trains across the Midwest for nearly two decades.

Dead or alive

But the crime spree eventually had to come to an end. On April 3, 1882, Jesse had just finished breakfast in his rental house in St. Joseph, MO, along with new gang members Robert and Charley Ford (Frank was not there). Jesse noticed a crooked picture on the wall and stood up to straighten it (some accounts say he reached to dust it off). While he was distracted, Robert shot and killed him. Yes, the notorious leader of the James Gang, who had eluded capture for years, was taken out in a moment of housekeeping.

As it turned out, both Ford brothers had been working with Missouri governor Thomas T. Crittenden, and Robert wanted the $5000 bounty on Jesse’s head.

Jesse James was no Robin Hood

Due to their string of successful robberies, the James brothers became celebrities of their time. In some circles, Jesse was revered as a Robin Hood figure. For example, in the 19th-century folk song “Jesse James” (first recorded in 1919), two of the stanzas are as follows:

Jesse was a man, a friend to the poor,

He'd never rob a mother or a child,

There never was a man with the law in his hand,

That could take Jesse James alive.Jesse was a man, a friend to the poor,

He'd never see a man suffer pain,

And with his brother Frank he robbed the Chicago bank,

And stopped the Glendale train.

But don’t let the song and legends fool you. In reality, the James brothers and the rest of their gang were criminals who committed crimes for their own enrichment. History suggests they weren’t terribly bothered by the collateral damage (Jesse himself was responsible for 16 murders). And despite the folklore, there’s no evidence that they redistributed any stolen money to the poor. Historian Milton Perry noted in 1979 that the James Gang was “innovative” because they stole from institutions rather than individuals. “People sort of applauded and envied anyone who could rob those hated institutions.” But that didn’t make them kind or altruistic.

Further tarnishing their legendary status, it’s worth noting that when they robbed a train in Iowa in 1873, they wore Ku Klux Klan masks.

The (not so) final resting place of Jesse James

Because of his fame, Jesse James’ shooting was a huge story, and the funeral proceedings generated a lot of interest.

After his death, James’ body was brought to his family home in Kearney under guard. According to an account by St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter Robertus Love (who later wrote a biography of James), “at all stations along the road, crowds gathered, anxious to see the body, the family, the officers, or anything.” (Reading the account made me think of the Beatles’ first visit to the US.)

Once in Jesse’s hometown, the coffin was placed on two chairs in Kearney House, a local hotel, and the lid removed so the body of Jesse James could “lay in state” and be viewed as a curiosity by the townsfolk, many of whom did not know him and had never seen him when alive. He was then buried in the family plot in the front yard of his mother’s home. As a modern reporter put it, “his grave marker matched his ego and towered over its visitors.”

Jesse James might have been dead and buried, but for years, his mother, Zerelda James Samuel, feared grave robbers would dig up her son’s body for profit or medical experimentation. Indeed, many people had approached her with offers to purchase his corpse so they could exhibit it in a traveling circus. She turned down all such offers and stood vigil in her front window for years guarding the grave.

Although feared someone else would try to make a buck on her dead son, it turned out that Zerelda wasn’t above doing it herself. She charged visitors 25 cents to visit the grave and take a tiny pebble from the site, which she regularly replenished from a local creek.

Eventually, the family decided to relocate the body. In 1902, Jesse James’ son Jesse Jr. (known as ‘Little Jesse’), along with the local gravedigger and his nephew, dug up Jesse Sr.’s coffin. The soil was hard and dry, making the task difficult, but matters were further complicated by the fact that Jesse’s mother had requested the grave be seven feet deep.

Eventually, they reached the metal coffin. However, when the gravedigger pulled it out of the ground, it fell apart, and Jesse’s skull fell back into the grave.

Once retrieved, Jesse’s half-brother John Samuel picked up the skull and examined it for the bullet hole, which he found behind the left ear. Little Jesse likewise looked at the skull, and with the bullet hole and gold teeth, confirmed it was his father. This identification reassured the family that the grave had never been disturbed.

For the new funeral, Jesse’s body was placed in a new black coffin with a silver plate bearing the name “Jesse James,” and was taken to Mount Olivet Cemetery in Kearney.

Love reported that hundreds of townspeople gathered for the second funeral. Love reported that after the reinterment was complete, Frank James turned away and said, “Well, boys, that’s all we can do.”

Imposters

After Jesse James’ death, many people wanted to capitalize on his fame. And one way to do that was to claim they were the real Jesse James.

According to the Jesse James Birthplace museum website, there have been at least 26 men claiming to be the outlaw.

One of these imposters surfaced in 1902. While digging up and reburying Jesse James, the Kearney city marshal received a letter signed by the “Original Jesse James,” who said he would not be buried in the cemetery. “I am not dead,” the letter writer claimed, “Tom Howard was shot by Robie, but I wasn’t there, so you can’t bury me.” (Tom Howard was Jesse’s alias.) But nothing more came of that claim.

A more compelling imposter was a Texan named J. Frank Dalton, who maintained for over 20 years that he was the real Jesse James. In the 1940s promoter Rudy Turilli, who at the time operated Meramec Caverns, claimed that the caverns had been Jesse James’ hideout. (Indeed, I remember this being a huge gimmick when I visited the caverns in the early 1980s). Furthermore, Turilli put Dalton forward as the real Jesse James. According to the two men, Robert Ford never shot Jesse James. Instead, the victim of the fatal shot was Charles Bigelow, who was posing as Jesse while the real outlaw escaped to South America. In 1950, Dalton even tried to change his name to Jesse James but was unsuccessful.

Dalton died in 1951, but Turilli’s scheme didn’t die with him. In 1967 Turilli, now the manager of the Jesse James Museum in Stanton, MO, offered $10K on a TV show to anyone who could prove that Dalton wasn’t the real Jesse James.

Stella James, the 85-year-old daughter-in-law of Jesse James, took offense. She provided affidavits proving her father-in-law had died as history claimed. Turilli refused to pay, claiming her evidence was too flimsy, so she took him to court. Among the documentation she provided was an affidavit from Thomas Mimms, who had signed the document in 1938 stating that he was Jesse’s brother-in-law and that he had positively identified the body in St. Joseph the day after Jesse’s murder. A jury decided in James’ favor in May 1970, which should have put the matter to rest.

Because the controversy wouldn’t die, in 1995 there was another exhumation of Jesse James, this time with DNA testing led by James Starrs, a law and forensic science professor at George Washington University. Starrs used genetic material provided by living descendants to positively identify the body in Jesse James’ grave was, indeed, the outlaw.

But truth and science didn’t stop the claimants. In 1997 Texas Monthly featured the story of Betty Dorsett Duke, who was convinced that her great-grandfather James Courtney was actually Jesse James, and notes her ancestor died in 1943, not 1883, so the man buried in Kearney couldn’t be Jesse James. She would write three books about her tenuous connection to the outlaw, including The Truth about Jesse James. This is the Amazon description:

Despite 1995 DNA results highly touted as proving Jesse James was shot dead by Bob Ford in 1882 and is buried just as history reports, he instead pulled off one of the biggest hoaxes in American history by getting away with his own murder, and hightailing it to Texas where he lived under the alias of James Courtney for the rest of his long life.

Meanwhile, the DNA test didn’t stop those on Team Dalton either. In an ironic twist of fate, just like Jesse’s, Dalton’s body was exhumed in 2000. Or so they thought—as it turned out, they dug up the wrong man, and since then, no one has been back for a re-do.

Robert Jackson, great-grandson of Susan James (Jesse and Frank’s sister), said in 2000, “I don't know how many people claim Jesse James is buried in Texas. They're all impostors as far as I'm concerned. But I'm willing to donate blood and hair if they're willing to get quality people to look at it."

So despite a mountain the evidence suggesting Jesse James died in 1882 and is buried in a cemetery in Kearney, MO, there are people to this day who refuse to believe it (and continue to publish new books trying to squeeze a bit more cash out of the theory). The Jesse James imposter circus Jesse James may never go dark.

Then again, who’s to say Jesse James wouldn’t approve?

Frank James did things differently

Finally, we return to Frank James.

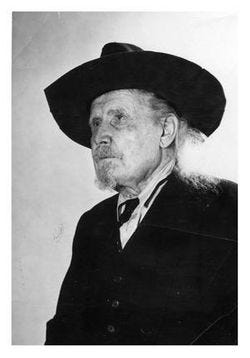

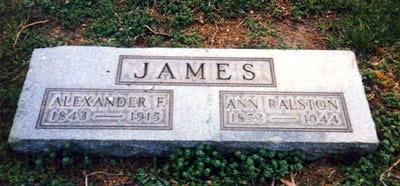

In Hill Park, Independence MO, there’s a small private cemetery. Tucked away in this cemetery is a modest stone marking a James family grave, naming the husband as Alexander F. and the wife as Ann Ralston.

But the man buried there isn’t named Alexander. It’s Frank—Frank James.

As a Post-Dispatch story described in 1993, “Jesse James sought fame and enjoyed creating fear. Frank James thought his brother careless and rash.” And contemporary reports described Frank as “quiet and gentlemanly,” an educated man who likely made all the plans and methods of escape, while Jesse liked notoriety.

And in death, just as in life, the two brothers were just as disparate.

After his brother’s death, Frank negotiated his surrender with the same Missouri governor who had put a price on their heads. And his luck was better than Jesse’s—he was tried twice for murder, but was acquitted both times. After that, he roamed the country, living in St. Louis between 1894 and 1901, and worked at the Standard Theater downtown, which was located at Seventh and Walnut streets, one block north of Ballpark Village.

As he got older, Frank wanted to avoid the circus that surrounded his brother’s death for decades. He even turned down $1000 a week to go into show business, saying in 1887, “I would never think of going into that business. No money would induce me to enter it.”

But how could he ensure he wouldn’t become the latest sideshow or scam after he died?

Frank decided that he wanted to be cremated, a process that back then was very uncommon. When he died in February 1915 at the family farm, his wife Annie arranged for her son Rob and nephew Little Jesse to bring his body to St. Louis. She gave them strict orders that the body would never be left alone until the ashes were returned to her. So Rob and Jesse Jr. remained at the crematory as Frank’s body was placed into the retort for cremation.

From there, Frank’s remains were held in a bank vault for safekeeping until his wife's death. After she passed in 1944, she was also cremated and both were interred in the unassuming cemetery in Independence.

A wild ride

So that’s the story of the deaths of Jesse and Frank James—which is a lot more than I expected to learn when I asked, “why was Frank James cremated in St. Louis?”

I hope you enjoyed it. Thanks to Amanda Clark for introducing me to a strange little piece of history, my friend Sara Anbari for the link to the “Ask a Mortician” video about Dalton (definitely worth a watch!), and Steve DuLany for being willing to show us what was in the book behind him.

If you enjoyed this article, I’d love it if you’d subscribe to Unseen St. Louis (it’s free!), and be sure to share it with your friends.

Sources and further reading

Associated Press, “For Frank James, Lonely Grave Is Monument to Troubled Life,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 7, 1993.

Associated Press, Grave Bearing Jesse James’ Name Is His, The Spokesman-Review, Sept. 24, 1995.

J. A. DACUS LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES: THE NOTED WESTERN OUTLAWS. 1880.

Anne Dingus, Body of Evidence, Texas Monthly, August 1997.

Iconic Corpse: The Exhumations of Jesse James, Ask a Mortician (YouTube), June 2020.

Eric James, Stray Leaves: The official website of the family of Frank and Jesse James (blog and other resources, current as of Oct. 2022).

Scott Kraft, “Wanted: Jesse James’ Real Story,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 24, 1979.

Robertus Love, GRAVE: ntrell's Comat. SAW CHANGE HOLE AND GOLD TEETH INDENTITY. Correspondent Describes Scenes Attending the Removal From Mother's Yard to Kearney Cemetery, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 30, 1902. [Part of title of article lost; title reported as in archive].

Robertus Love, “The Rise and Fall of Jesse James,” chapter 33, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 19, 1925.

Penny Owen, Outlaw won't rest in peace Purcell man hopes to uncover evidence of Jesse James' long life, The Oklahoman, May 6, 2000.

Michael S. Rosenwald, On this day in history, outlaw Jesse James took a bullet to the brain, Washington Post, April 3, 2017.

Patrick Strickler, “Jesse Laid In His Grave in 1882, Jury Decides,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 8, 1970.

“On Ice. The Body of the Dead Bandit Jesse James,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 5, 1882.

“James in Jail. The Famous Bandit Feted by His Old Associates.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 9, 1882.

Frank James’ Body to Be Cremated Here. Ashes Will Be Put in Safety Deposit Box. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 19, 1915.

“Frank James. The Former Bandit Visits St. Louis in Search of Work,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 12, 1887.

Photos: Inside the old Missouri Crematory at Valhalla's Hillcrest Abbey, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Oct. 25, 2019.

Jesse James, Historic Missourians, State Historical Society of Missouri.

Jesse James Grave Mix-Up, CBS News, June 30, 2000.

Zerelda James at Jesse James’ Grave, Kansas City Public Library.

Zerelda James, PBS American Experience.

Sometimes it pays to be curious! This was a great read, Jackie. Thanks for putting this little piece of history together. 👍

What a story!