A Warehouse that Kept St. Louisans Fed for almost a Century

Another fire - this time at the former Federal Cold Storage Building

Welcome to another historical moment from Unseen St. Louis. Once again, a fire is ravaging a historic warehouse in North St. Louis, and once again, I couldn’t help but dig into the history of the building.

A caveat: I put this article together within the span of a few hours, leaning heavily on materials from the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form filed in 2009. I’m also fighting a cold or allergies. So this piece may be a little rough around the edges, but it felt important to publish it while the building still stands. As always, if you have additional details about the building or any photos, please let me know in the comments or via email.

I’ll post updates at the end of this article.

On the afternoon of Monday, October 14th, firefighters were called to battle a blaze at the historic Federal Cold Storage Building at 1800-1828 N. Broadway in St. Louis, adjacent to the I-70 entrance to the Stan Musial Bridge. This 1922 industrial warehouse, once the largest cold storage facility west of the Mississippi, played a crucial role in keeping St. Louisans fed for decades by storing and distributing perishable goods and distributing them throughout the city and beyond. Now, with flames still burning inside the thick, window-less walls, this building joins a growing list of historic North St. Louis warehouses that have been lost to similar tragedies in recent years. (If you’re curious, I previously wrote about both the Shapleigh and Beck & Corbitt warehouse fires here on Unseen St. Louis.)

As the city grapples with the loss of its industrial past, the Federal Cold Storage Building stands as a reminder of both the importance of these structures in shaping the region’s economy and the challenges of preserving them in the face of time, neglect, and once again, fire.

Architectural Features

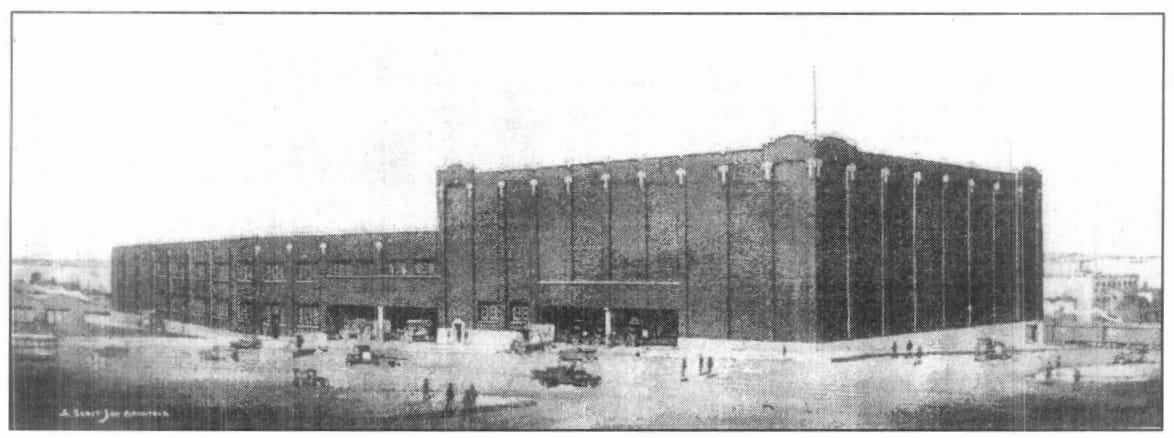

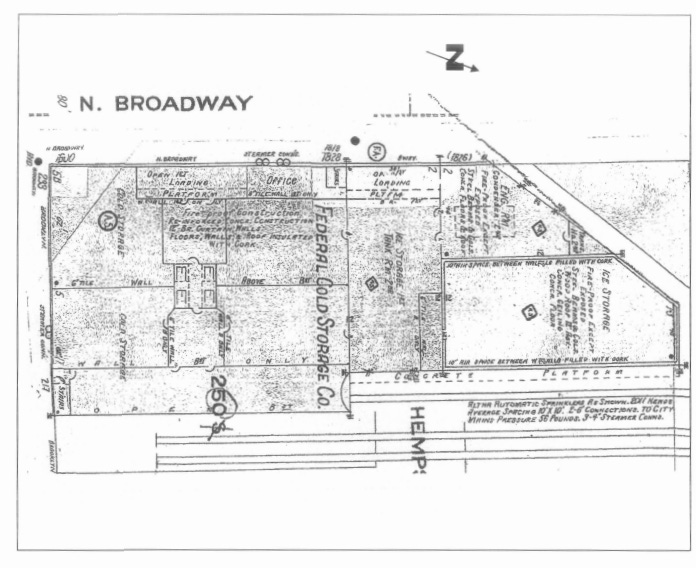

The Federal Cold Storage Building was constructed in 1922. Its multi-colored brick facade is complemented by Art Deco terra cotta detailing, with its four-story warehouse sitting prominently at the corner of North Broadway and Brooklyn Street. An attached two-story tank storage room, engine room, and three-story ice storage room are located on the north side of the structure.

The warehouse itself is nearly windowless, save for three boarded-over openings on the first level. The building's distinctive features include brick pilasters topped with cruciform terra cotta caps and parapets with terra cotta detailing at the corners.

Architect S. Scott Joy’s design for the building was both innovative and practical. The building’s design included features specifically meant to support cold storage operations: thick concrete walls faced with 12 inches of brick; 1,700,000 feet of pure corkboard insulation; and metal pipes that pumped cold brine through the ceilings to maintain temperatures between 35 degrees Fahrenheit and 20 degrees below zero. The interior layout featured overhead chains for loading ice, which was produced onsite and used to refrigerate railcars quickly. These advanced features allowed Federal Cold Storage to maintain a dominant position in the industry for many years.

Its most innovative feature was the internal railcar switch, which allowed Terminal Railroad cars to access the building’s temperature-controlled loading dock. This design allowed perishable goods to be loaded and unloaded directly, reducing the risk of spoilage and making the cold storage process more efficient. This direct connection to the Terminal Railroad’s tracks was a key feature that gave it a competitive advantage over other local cold storage facilities.

As of 2009, when the Missouri Department of Natural Resources filed to add the building to the National Register of Historic Places, the open floor plan remained largely intact, with original mushroom-shaped supports reinforcing the warehouse and ice storage rooms. Historic mechanical systems remained in the engine rooms, and the warehouse freight elevators were in working condition. Those reviewing the building considered it to have strong structural integrity due to its thick reinforced concrete walls and 12-inch brick curtain walls holding up well over the years.

Historical Significance

The building is a significant artifact of the rapidly industrializing city of St. Louis. The neighborhood, just north of downtown, had transitioned from residential to commercial and industrial use by the early 20th century. Located near major railroad depots along the Mississippi riverfront, the area served as a bustling hub for goods distribution. (As an aside, the location sits near the former site of Big Mound, a significant landmark of the region's Indigenous peoples, which was sadly demolished decades before the cold storage building’s construction.)

The growing demand for cold storage to manage perishable goods prompted the construction of facilities like the Federal Cold Storage Building. The building's prime location near railroad depots ensured it was a key part of the industrial supply chain that kept food fresh for St. Louisans.

T\he Terminal Railroad Association, which owned nearby depots, had been a major force in driving the establishment of businesses around the area. By the early 1900s, investors were developing cold storage warehouses to store goods arriving by rail, especially perishables. St. Louis’s "Produce Row" was located nearby, which made the area an ideal location for a cold storage facility.

When the Federal Cold Storage Company Building opened its doors in 1922, it was the largest cold storage facility west of the Mississippi River, boasting 3,000,000 cubic feet of warehouse space. The building then operated as a critical part of St. Louis’s cold storage infrastructure for nearly 40 years. During this time, it helped keep the city’s residents fed by storing perishable goods like eggs, poultry, fruits, and vegetables. The building’s direct access to the railroad tracks enabled it to distribute products efficiently throughout the region and beyond. In its early years, it also produced the ice needed to refrigerate railcars, which allowed perishable items to be shipped across long distances.

The Federal Cold Storage Company continued to expand throughout the mid-20th century. In 1959, Federal Cold Storage sold the building to Gateway Refrigeration, which continued cold storage operations until the building was vacated in 2009. Despite some minor alterations for truck deliveries and other operational updates, the building remained largely unchanged during its decades of use.

Philip D. Ball: Cold Storage Pioneer

Philip D. Ball (October 22, 1864 – October 22, 1933) played a key role in shaping the cold storage industry in St. Louis. In 1883, he co-founded the Ice and Cold Machinery Company with his father Charles J. Ball, who was a pioneer in ice production and had installed an ice-making machine in Sherman, Texas, that could produce five tons of ice a day. (No more cutting blocks of ice from the Mississippi River!) This early venture into ice-making set the stage for Philip Ball's later success with the Federal Cold Storage Company in St. Louis.

The Balls’ innovative approach to refrigeration technology quickly gained attention, revolutionizing the ice-making industry. Philip Ball’s company produced advanced refrigeration systems, like the giant compression and absorption machines that became the go-to for meat packing plants.

Ball is better known for his role as president/owner of the St. Louis Browns, Milwaukee Brewers, and Texas League baseball teams, but his real pride seemed to be his cold storage empire. He once confidently declared that the Federal Cold Storage facility would be "equal if not better than any plant in the West."

The Warehouse’s Legacy

Today, the Federal Cold Storage Building is the only remaining cold storage facility from the early 20th century in St. Louis that was directly connected to the railroad. While many of its competitors have been demolished or repurposed, the Federal Cold Storage Building is a testament to St. Louis’s industrial heritage. Its design, which allowed for efficient handling of perishable goods, helped shape the city’s economy by supporting the cold storage needs of local industries and residents.

The building is significant not only for its size and functionality but also for its role in facilitating St. Louis’s growth as a center for industrial and commercial activity. It helped the Terminal Railroad compete with other rail lines by offering seamless cold storage services, and its innovations in refrigeration technology kept St. Louisans supplied with fresh food for almost a century. Even today, it continues to evoke the city’s past as a hub of industrial innovation.

Current status

The St. Louis Fire Department first responded to the fire in the noon hour on Monday and posted an initial Facebook update shortly thereafter. As of 8:00 pm, the fire department reported that the fire still burned, and they planned to watch it for the next week. It hadn’t breached the (thick) outer walls but was consuming a lot of fuel inside. Given all of the cork insulation, it seems likely that the fire could continue for some time to come. Because of its proximity to the Stan Musial Bridge, the bridge is closed for the time being due to low visibility from the smoke.

Update from overnight from the St. Louis Fire Department: the fire reached the outside of the building. They expect this to be a long process.

KSDK did a report Tuesday night. Apparently, the current owner was supposed to close on the sale of this building this week and had no insurance on the building. Oh and yes, the building is still on fire.

As always, thanks for your support. Unseen St. Louis is always free to read, but if you like what I’m doing, consider a paid subscription.

And please help Unseen St. Louis grow! Share this article with others who may appreciate it.\

Sources

Kevin Bair, “The Civil War, The Ice Trade, And the Rise of the Ice Machine,” Kevin Bair (blog), August 25, 2020.

“Philip De C. Ball, Sportsman, Dies,” New York Times, October 23, 1933

Federal Cold Storage Company Building, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, November 24, 2009.

“Philip D. Ball, St. Louis Cold Storage Leader, Dead,” Chicago Packer, 28 October 1933.

Phil Ball (baseball), Wikipedia

Philip De Catesby Ball, Find a Grave.

St. Louis Fire Department’s Facebook Page

“Musial Bridge to be closed for up to two days due to abandoned warehouse fire,” First Alert 4, 14 October 2024.

A shame. It was a neat old building that I’ve enjoyed photographing in the past.

My dad was a refrigeration engineer and worked here for 10 years (1995-2005) until he retired. At the time, the owner had been told that it was going to be a casualty of the new bridge, so they moved over to another cold storage warehouse in Illinois.