This week in Unseen St. Louis: let’s visit the unusual bridge known as the Chain of Rocks Bridge and the fascinating history of the area around it.

The Chain of Rocks Bridge has been a part of St. Louis history for nearly 100 years and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2006. As one might expect with such a designation, there’s a lot of history about this bridge, as well as the surrounding area.

There’s a lot we can talk about, so let’s dive right in!

History of the area

The Chain of Rocks Bridge is located 12 miles north of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis.

The bridge was named after a formation within the Mississippi River known as the ‘chain of rocks’. Just south of the bridge is a stretch of rocky rapids that made this segment of the river difficult to navigate. The rapids were formed during the last ice age, when the river changed course, flowing over a ledge of limestone that hadn’t eroded to the level of the rest of the river.

The area is also marked by three islands: Chouteau Island, Gabaret Island, and Mosenthein Island which combined make up 5,500 acres. Although Gabaret Island and Mosenthein are naturally occurring, Chouteau Island was created during the construction of the Chain of Rocks Canal.

Many people lived on Chouteau Island in the past, but some were forced off the island due to flooding in the 1970s. Those who remained had to abandon their homes after historic flooding in 1993. Nowadays, the land around the Chain of Rocks, and the entirety of the other two islands, provides wildlife habitat and flood storage and is managed by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

Intake Towers

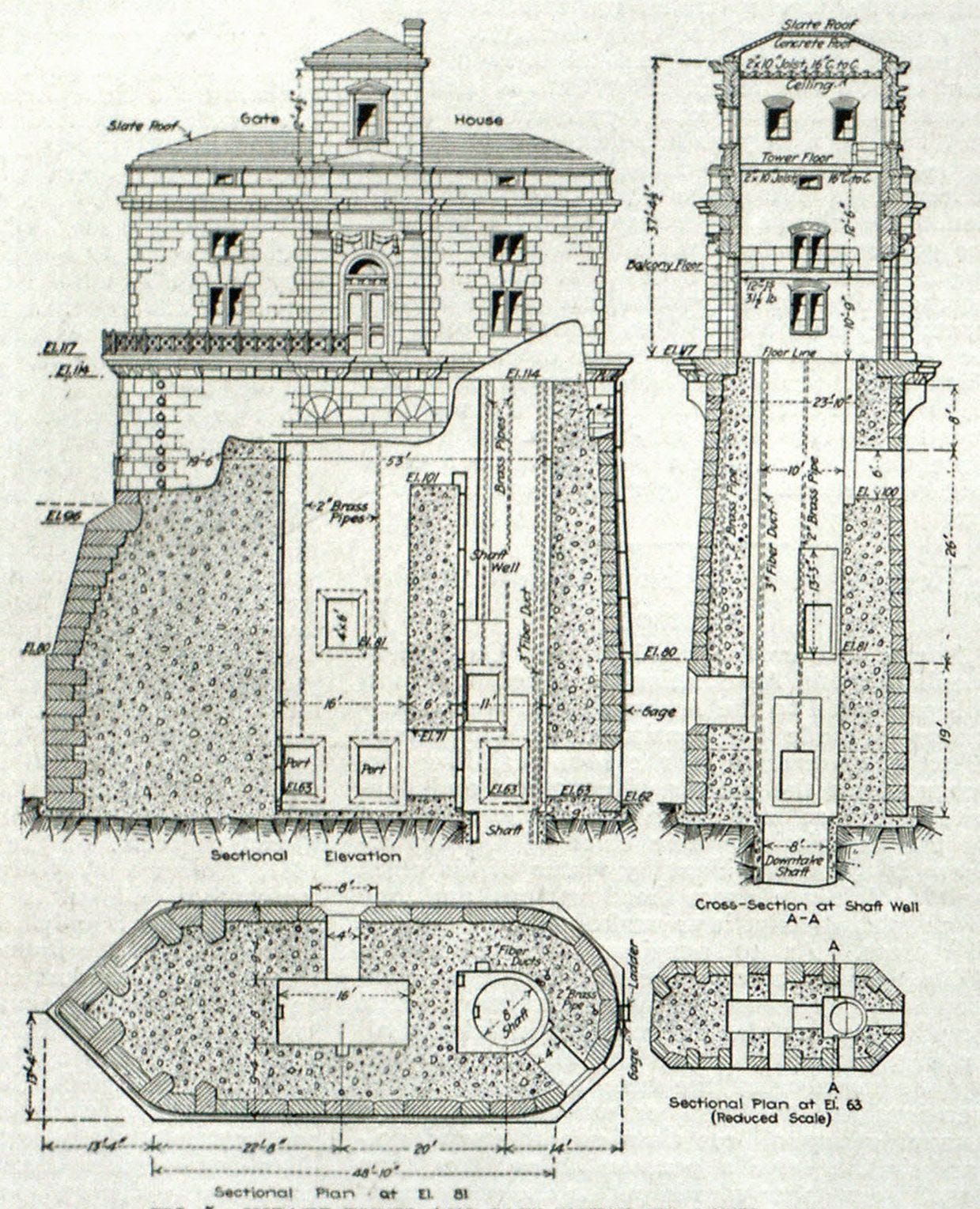

What are those two castles in the river? They’re water intake towers, and they provided water to the city of St. Louis for well over a century.

In 1871, the St. Louis Water Works was created after a bond issue. The Water Works included building a water intake tower on the river and the construction of settling tanks (to clear the water) north of downtown, as well as the Compton Hill Reservoir and the Grand Avenue Water Tower in the city.

The first water intake tower, and the larger of the two, was designed by William S. Eames in the Romanesque Revival style and was built in 1894. The second tower was designed by the St. Louis firm of Roth and Study in 1915.

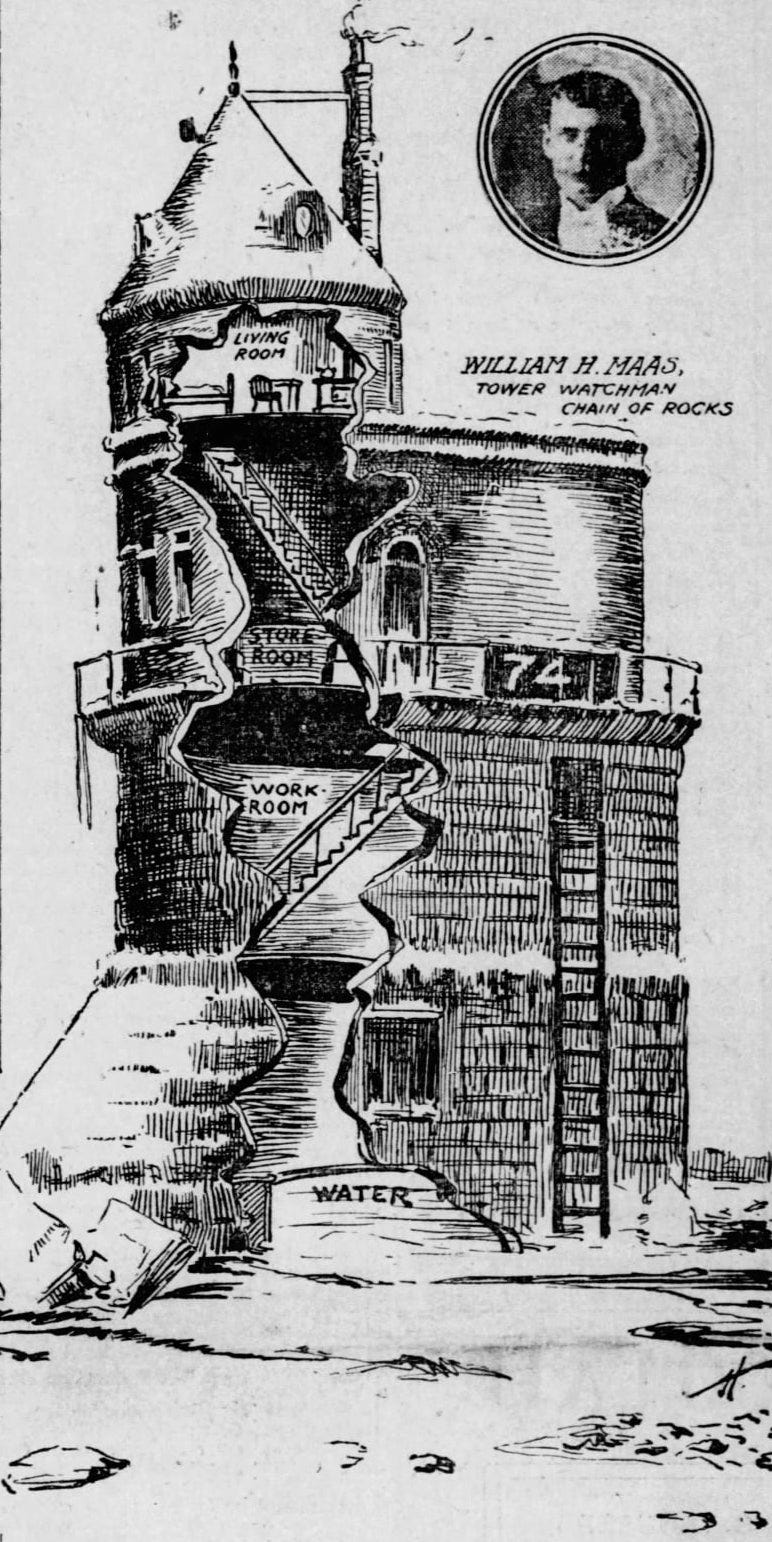

The towers needed regular maintenance to ensure machinery was operating properly. This was particularly important in the winter when ice could clog up the intake and prevent the city from getting an adequate water supply. In fact, in January 1904 the river froze, and William Maas had to stay at the his intake tower longer than usual in order to break up the ice.

The Post-Dispatch recounted how the keeper telephoned to say he was running out of provisions, and several attempts were made to deliver new supplies, with the boats struggling to reach the tower and one man falling overboard and nearly drowning. Maas himself recounted the difficulties he experienced:

This has been the hardest winter I have ever experienced at the tower. I am afraid I should have given out if the brave fellows had not reached me last night. Nobody who has not made that trip under such circumstances can understand what it means.

He went on to discuss how hard he had to work to keep the ice out of the intake, and how it was difficult to go so long without the necessities of life:

It is a might easy thing to go insane when one is shut off from the world with no one to look at or talk to, and no tobacco.

He described it being an especially lonely winter, as his wife had stayed with him in previous years, but they had a new baby and she didn’t join him that year. Although he usually only stayed at the tower for a few days at a time, by the end of January 1904 he had been at the tower for over two weeks and expected to be there a while longer.

Today no one lives in the intake towers, but the city still gets some of its drinking water from Intake Tower #1.

For more on the intake towers, here’s a nice video of bridge and intake tower exteriors, and here’s a site with some interior photos of one of the intake towers.

The Chain of Rocks Bridge

In 1927 Congress granted a charter to build a toll bridge over the Mississippi at the Chain of Rocks with a projected cost of $1,250,000.

The initial plan for the bridge was a straight bridge, 40 feet wide, with five trusses forming 10 spans. The bridge would stand 55 feet above the high-water mark on several massive piers. After seeing the initial designs, boat captains protested that the river was already difficult to navigate at this location, and the river current would make it impossible to avoid the bridge piers and the water intake towers. Furthermore, the bedrock was insufficient to support the weight of the piers in their original position. To address engineering issues as well as the concerns of the riverboats, designers added a 24-degree bend in the bridge so that it could connect to the promoter’s property in Missouri and to bedrock on the Illinois side.

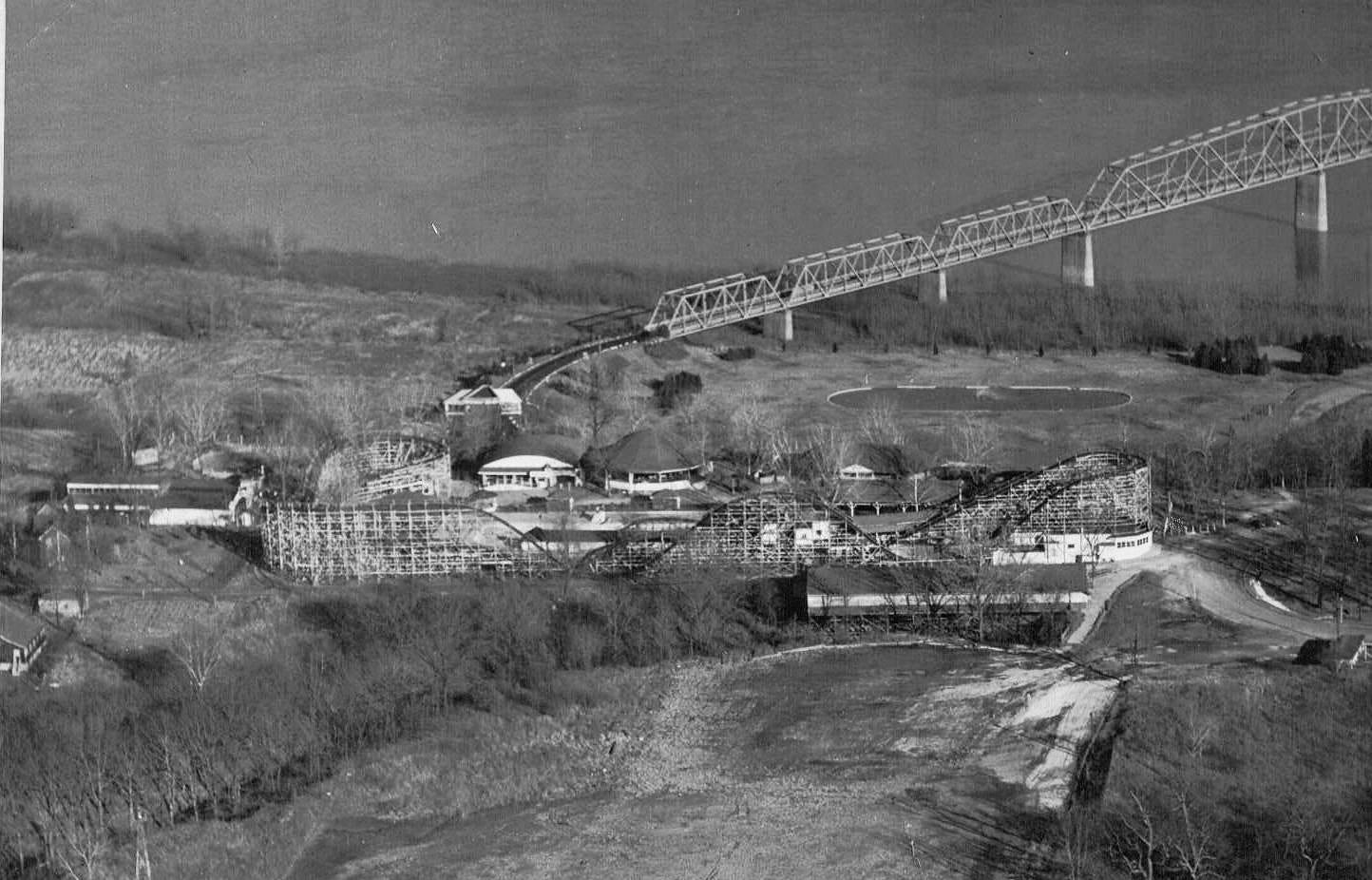

The Chain of Rocks Bridge opened to traffic in July of 1929, costing $2.5 million, and both approaches were landscaped, with the Missouri side marked by the new amusement park. Then in 1936 Highway 66 was rerouted to go over the bridge.

The Chain of Rocks Bridge was a toll bridge, bringing in $900,000 a year to the city of Madison IL in its heyday. Route 66 was redirected to the bridge, and the area was popular both with drivers and tourists.

Over time, the bridge became less and less desirable. Cars were getting bigger, and the narrow lanes were difficult to navigate. And the bend in the bridge caused numerous accidents over the years. When the new toll-free I-270 bridge opened 1000 feet upstream in 1967, the city of Madison removed the toll on the Chain of Rocks Bridge, but traffic quickly dropped from an average of 12,000 vehicles a day to fewer than 100. With the bridge all but abandoned, it cost the city $50,000 a year in repairs but was making no income.

Unable to maintain the bridge, Madison closed it in 1968. By 1975 the bridge was slated for demolition, at a cost of over $1 million to tear down the bridge, and even more to remove the piers. The city hoped to recoup some of the losses by selling the steel, but then the value of scrap steel plummeted. The cost of tearing the bridge down was deemed too high, and it sat unused for decades.

The bridge remained abandoned and unused for decades. It got a short revival in 1981 when John Carpenter used the bridge as a setting for the film, Escape from New York. You can see the bridge in the following video, when the yellow cab attempts to cross the bridge:

Chain of Rocks Lock and Dam

Today, barges move 175 million tons of freight each year on the Mississippi River. Such a feat is possible thanks to major engineering efforts in the 1940s and 1950s with the construction of the Chain of Rocks Lock and Dam, also known as Locks No. 27, the most southern lock and dam on the Mississippi.

For well over a century, 17 miles of limestone ledges that make up the chain of rocks had caused trouble for boats and barges trying to navigate the Mississippi River. To resolve this issue, between 1946 and 1953 an 8.4 mile canal was built on the Illinois side of the river.

The canal needed deep enough water for the ships that would use it, and to raise the level of the canal, engineers needed to raise the river level as well. So from 1959-1964 they built a low water dam just below the Chain of Rocks Bridge by dumping tons of rock into the river just downstream from the bridge. This dam raised the river by three feet, making the canal deep enough for navigation without having to cut into the bedrock.

What’s interesting about this particular dam is that it rests almost entirely underwater. If you visit the bridge today, depending on river levels you might see the river flowing over rocks and think you’re witnessing the chain of rocks that gave the bridge its name, when in fact you’re seeing the river cascading over the rock dam.

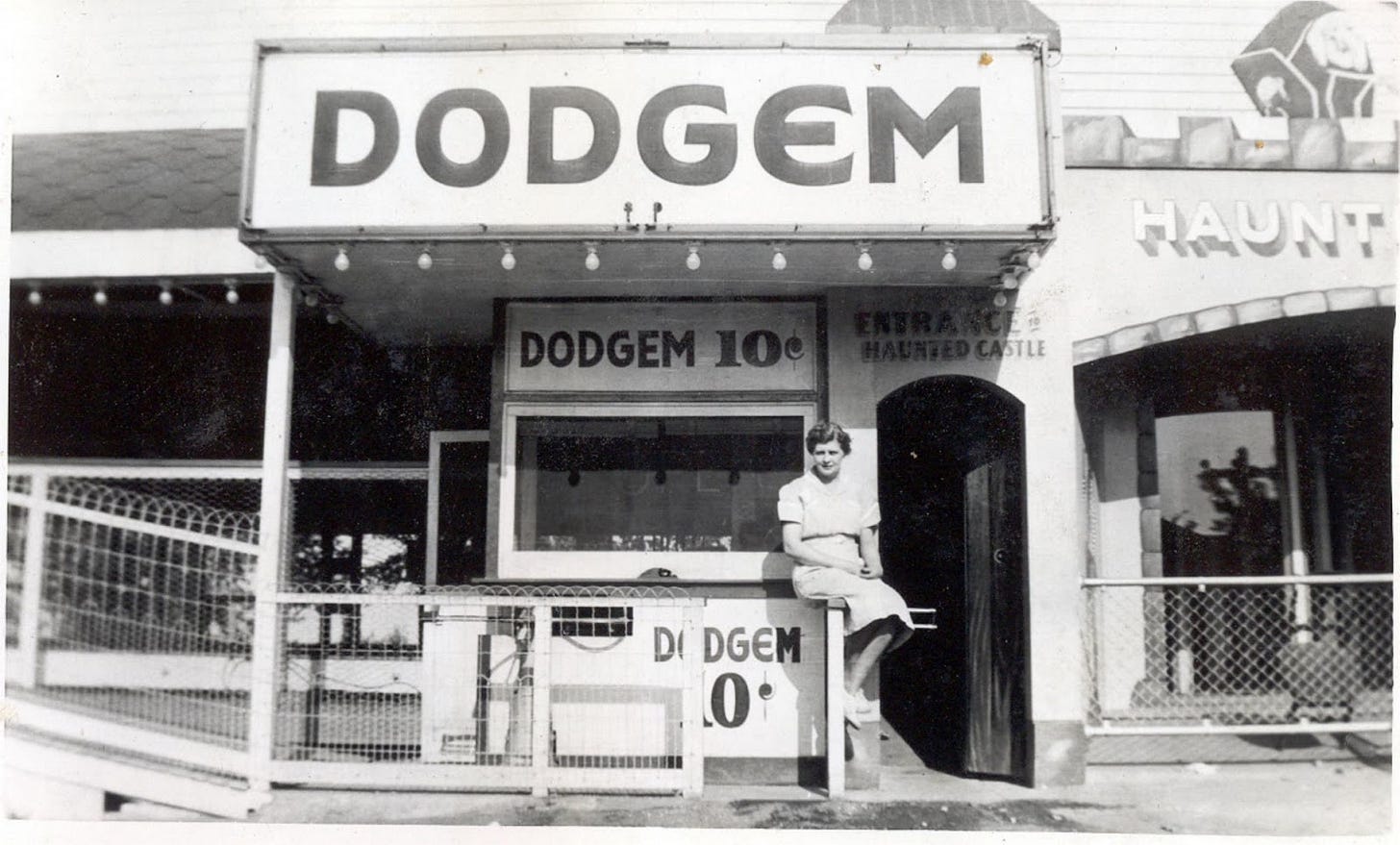

Chain of Rocks Amusement Park

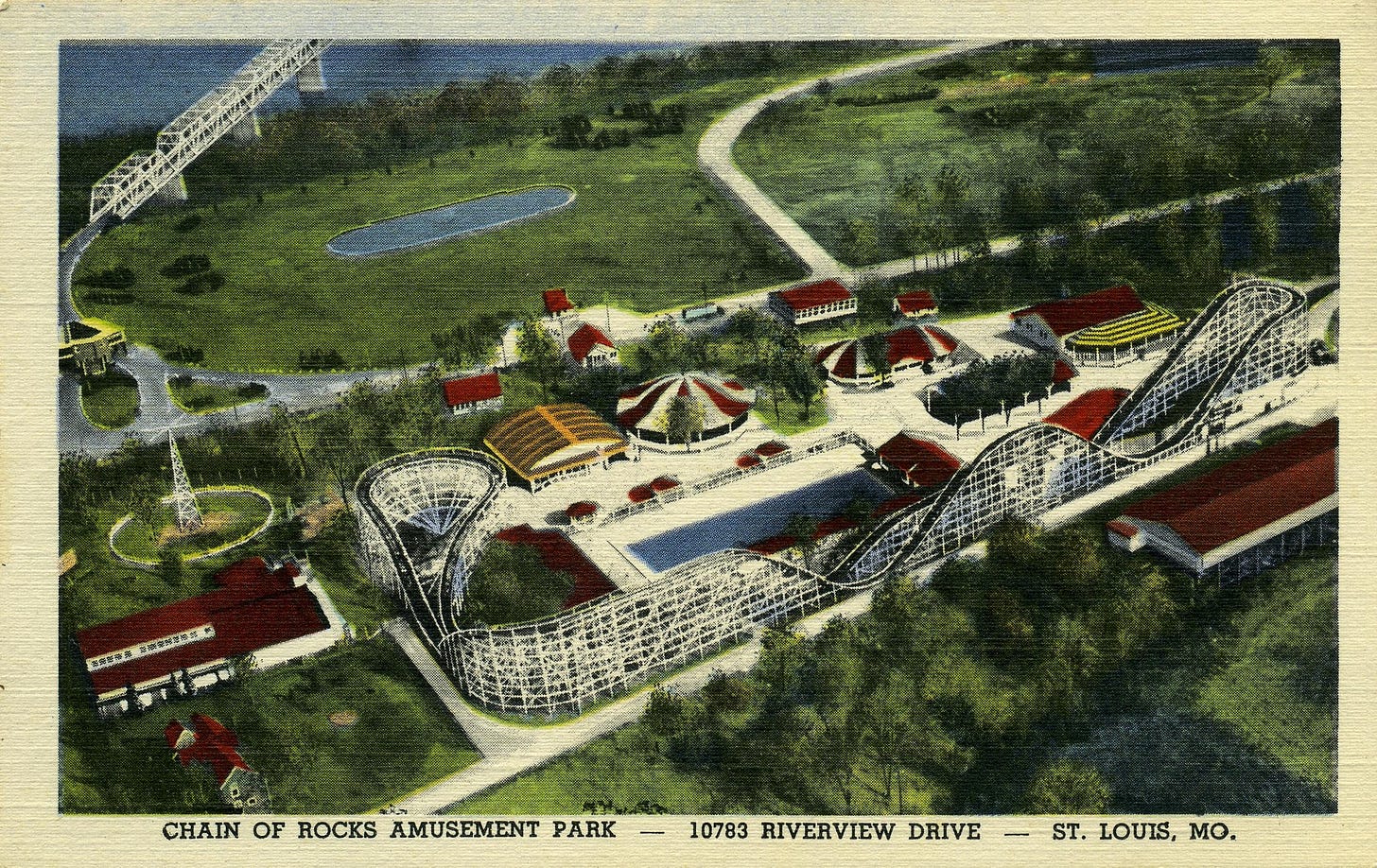

Illinois has the shipping canal, while for 50 years Missouri was home to the Chain of Rocks Amusement Park at the western approach to the bridge.

The park first opened in 1927 and was owned by Chris Hoffman. Carl Trippe of the Ideal Novelty Company purchased the park In the 1940's. Then in 1958 investors bought Chain of Rocks Park and Ken Thone managed the park until it shut down 20 years later.

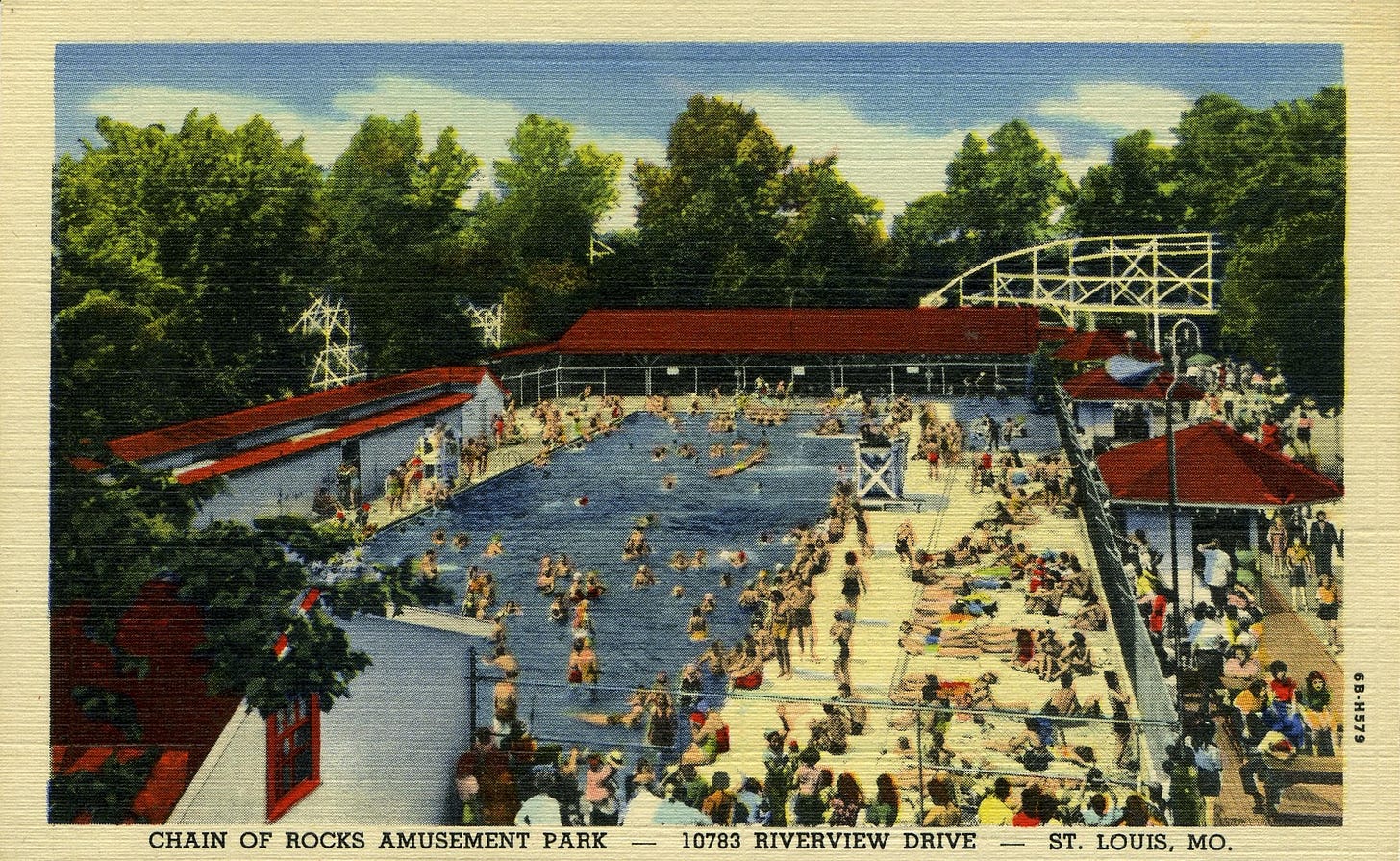

Over the years the park added a number of attractions, but among the favorites were a swimming pool, an area for picnics, and a number of thrill rides including the Comet, the big rollercoaster. Under the new management in 1958 the coaster was torn down, and although the owners wanted to build a new coaster, they couldn’t afford to do so. John Allen designed the Six Flags rollercoaster the Screamin’ Eagle as a larger version of the Comet.

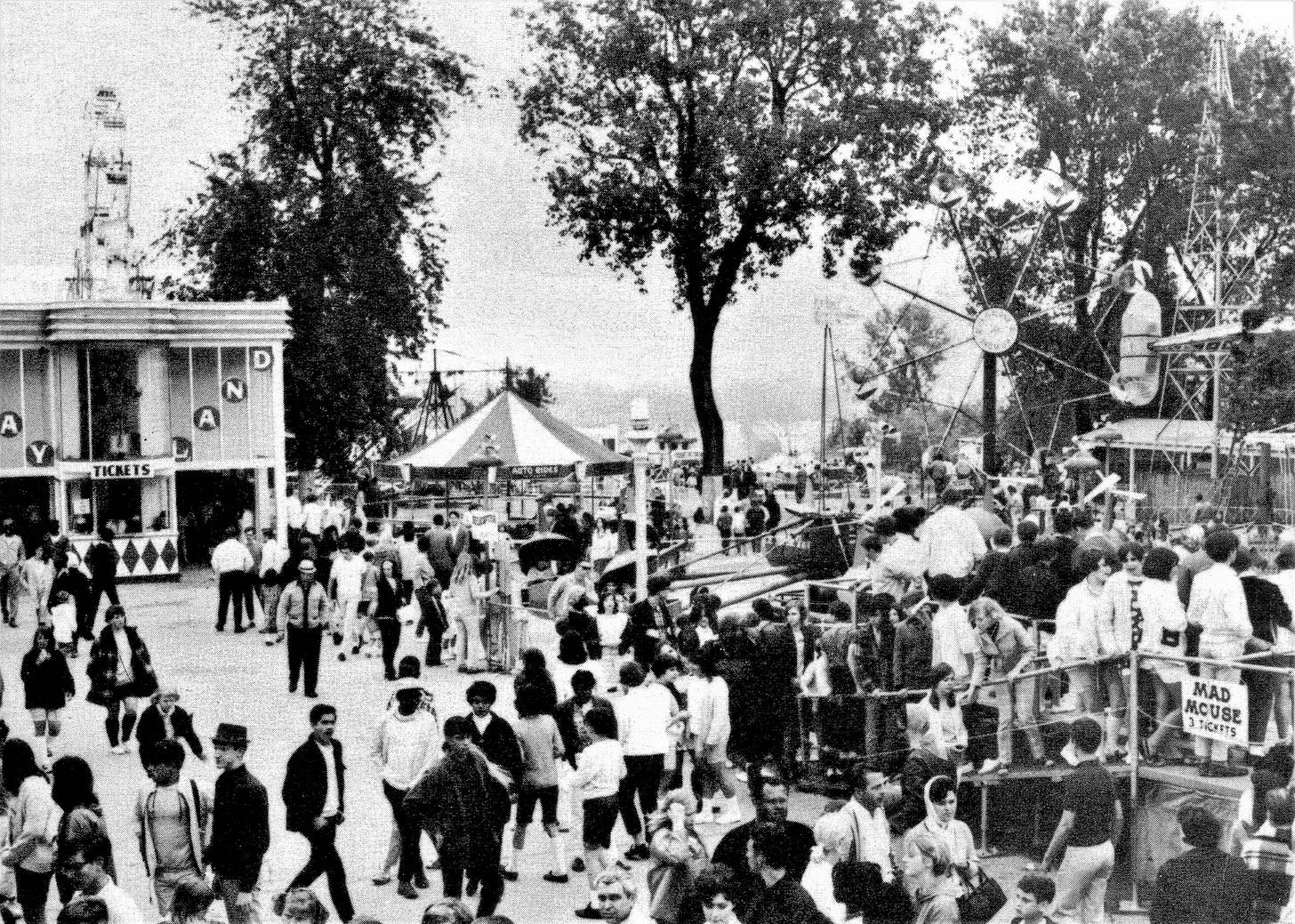

Here are some images from the Chain of Rocks Amusement Park over its 50-year run.

The Chain of Rocks Amusement Park was open until 1978, when two fires in four years, plus competition from the new Six Flags Over Mid America (now just Six Flags St. Louis) theme park in Eureka, brought an end to the riverside park.

Murders at the bridge

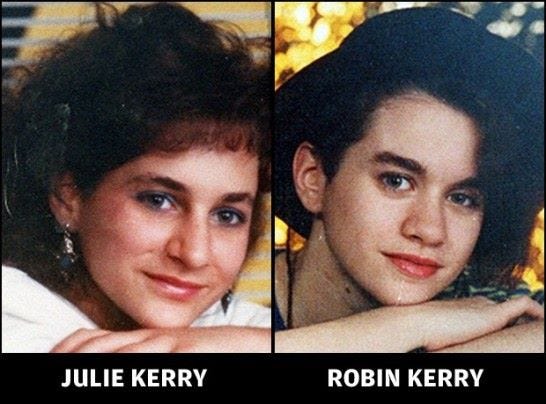

Not everything about the Chain of Rocks location represents fun and games. In 1991, two young women, Julie and Robin Kerry, were raped and murdered by a group of four men who also tried to murder their cousin Thomas Cummins.

Julie was 20, while Robin and Thomas were both 19. After the women were raped, they were forced off the bridge along with Tom. The women drowned; Tom survived the 48-foot fall and swam to shore.

In 2004, Tom’s sister Jeanine Cummins published her memoir A Rip in Heaven about the crime, which she wrote with her brother. The murders happened when she was 16. Ultimately Tom wasn’t able to represent the book, so Jeanine became the sole author and spoke about the traumatic incident on the press tour. “I had to go out and talk to people about the worst moment in my life,” Cummins told Publishers Weekly. “It was really tough, and I knew I never wanted to write anything like that again.”

What’s there today?

Today the amusement park is long gone, but the bridge remains, as do the lock and dam and both of the intake towers.

In 1997 Gateway Trailnet obtained a long-term lease to rehabilitate the bridge and turn it into a pedestrian crossing. Today it is a popular site for tourists, cyclists, and birdwatchers. The bridge is free to pedestrians and bicycles, but parking for the bridge is only on the Illinois side. (Missourians, don’t fret—the Great Rivers Greenway recently received a $990,000 grant from a National Park Service program and will be using that to improve the Missouri side of the bridge and reopen the parking lot. )

When you visit the bridge, you will enjoy a pleasant walk on an architecturally-interesting bridge, high over the woods and wetlands of Chouteau Island. You’ll want to keep a lookout down below for the birds and other wildlife that make the island home (when I was there I spotted a line of turtles). You will then feel the breeze off the water as you cross the Mississippi, of course delighting in the sight of the intake towers not far from the bridge itself. If you look out into the distance, you can even make out the Arch in the distance. Best of all, depending on the time of year, you might even catch a glimpse of a bald eagle overwintering in the trees.

If you take the road to the left just before you get to the bridge, you can visit the small beach favored by fishermen and beachcombers.

But whatever you do, don’t try to see the bridge by boat. Last October, a couple trying to sail down the Mississippi missed the turn for the canal and got stuck on the rocks. Although they were rescued, the sailboat sunk after a heavy rain a few weeks later.

As always, I hope you enjoyed this edition of Unseen St. Louis. If you like what you’re reading, please consider subscribing so you don’t miss the next one.

And if you have memories from the Chain of Rocks Bridge, amusement park, or anything else, I’d love to hear from you in the comments.

Very interesting and informative!! Love learning so of the History of area! Spent many hours in park and playing on old bridge! Thanks!

Wonderful! I grew up in Glasgow Village, spent many school picnics marching to the park. Great memories, thank you!